International guidelines emphasize the need to be active in order to prevent cardiovascular mortality. Credits : Adobe Stock

Physical activity is thought to be our greatest ally in the fight against cardiovascular disease. But there may be significant variations in its protective effects across a range of different situations, such as regularly playing a sport, carrying heavy loads at work, or going for a walk with friends. These are the findings of a new study led by Inserm researcher Jean-Philippe Empana (U970 PARCC, Inserm/Université de Paris) in collaboration with Australian researchers. The results have been published in Hypertension.

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of mortality around the world, and there is no sign that this trend is declining. However, a large number of premature deaths could be prevented by taking appropriate preventive measures. Among these measures, physical activity is often presented as having multiple benefits, and international guidelines emphasize the need to be active in order to avoid cardiovascular mortality.[1]

But physical activity is a broad concept, and few scientific studies have looked into the differences between various types of exercise may have. This was the focus of the new study published in Hypertension, which was conducted by the research teams led by Jean-Philippe Empana, Xavier Jouven, and Pierre Boutouyrie (Inserm/Université de Paris), in collaboration with Rachel Climie at the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute, Melbourne, Australia.

“Our idea was to look at whether all types of physical activity are beneficial, or whether under some circumstances physical activity can be harmful. We wanted in particular to explore the consequences of physical activity at work, especially strenuous physical activity such as routinely carrying heavy loads, which could have a negative impact”, explains Empana.

Sport, work, or leisure

The research by Empana and his colleagues was based on data from participants in the Paris Prospective Study III. For ten years, this extensive French study has been monitoring the health status of over 10,000 volunteers, aged 50 to 75 years old and recruited during a health check-up at the Paris Health Clinic (Paris Preclinical Investigations, IPC).

Participants were asked to fill out a questionnaire about the frequency, duration, and intensity of their physical activity in three different contexts: physical activity through sport, physical activity at work (for example carrying heavy loads), and physical activity in their leisure time (such as gardening).

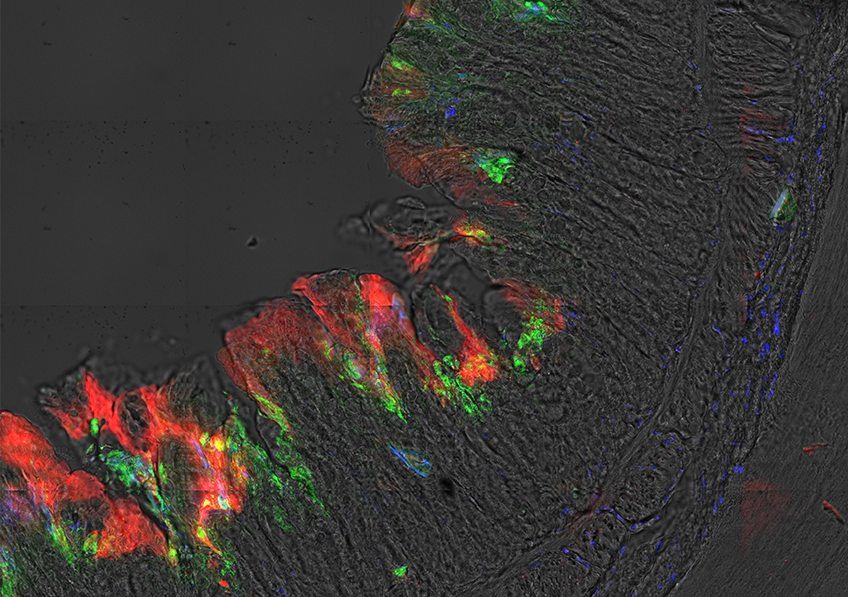

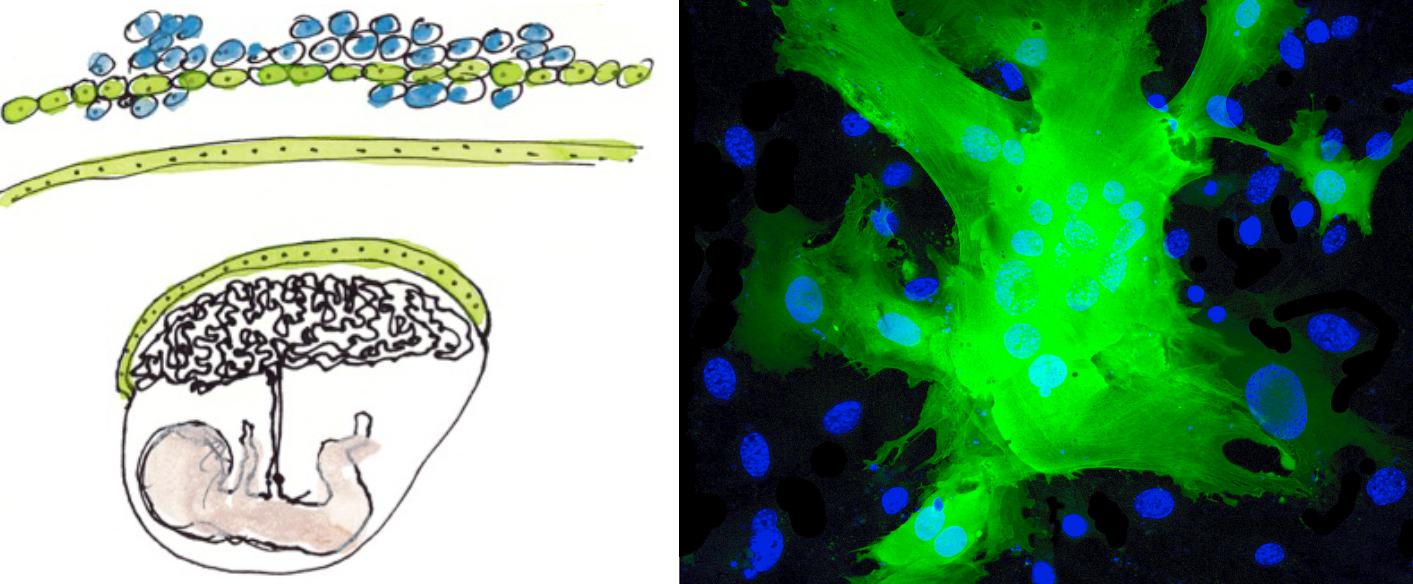

The cardiovascular health of participants was then assessed based on the health of their arteries using cutting-edge ultrasound imaging of the carotid artery (a superficial artery in the neck). This method, known as “echo tracking”, can be used to measure baroreflex sensitivity, a mechanism of automatic adaptation to sudden changes in blood pressure. When this system is impaired, this can lead to major health problems, and a higher risk of cardiac arrest.

Studying the arduous nature of work

In their analyses, the researchers distinguished between two components of the baroreflex: mechanical baroreflex, assessed through the measurement of arterial stiffness, and neural baroreflex, assessed through the measurement of nerve impulses sent by the receptors on the walls of the artery, in response to a distension of the vessel. Abnormalities in the mechanical component tend to be associated with aging-related cardiovascular diseases, while abnormalities in the neural component tend to be linked to heart rhythm disorders that can lead to a cardiac arrest.

The study shows that high-intensity sporting physical activity is associated with a better neural baroreflex. Conversely, physical activity at work (such as routinely carrying heavy loads) appears to be more strongly associated with an abnormal neural baroreflex and greater arterial stiffness. Such activity could therefore be harmful for cardiovascular health, and in particular may be associated with heart rhythm disorders.

“Our findings represent a valuable avenue of research for improving our understanding of the associations between physical activity and cardiovascular disease. They do not suggest that movement at work is harmful for health, instead they suggest that chronic, strenuous activity (such as lifting heavy loads) at work may be”, highlights Empana

The researchers will attempt to replicate these results in other populations, and explore in greater detail the interactions between physical activity and health. “This study has major public health implications for physical activity at work. We now want to expand our analysis to further explore the interactions between physical activity and the health status of people in the workplace”, concludes Empana.

[1] See the Inserm collective expert review: “Physical activity: Prevention and treatment of chronic diseases” https://www.inserm.fr/information-en-sante/expertises-collectives/activite-physique-prevention-et-traitement-maladies-chroniques