A study published in Science provides new insights into understanding post-traumatic stress disorder © Inserm

The terrorist attacks committed in Paris and Saint-Denis on November 13, 2015 have left lasting marks, not only on the survivors and their loved ones, but also on French society as a whole. A vast transdisciplinary research program, the 13-Novembre project is codirected by Francis Eustache, neuropsychologist and director of the Inserm Neuropsychology and Imaging of Human Memory laboratory (Inserm/Université de Caen Normandie/École pratique des hautes études/Caen university hospital/Cyceron imaging platform) and Denis Peschanski, historian and CNRS Research Director[1]. The program seeks to understand the ongoing construction and evolution of the individual and collective memory of these traumatic events and improve our understanding of the factors that protect people against the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Part of this program is a brain imaging study called Remember, which is focused on the cerebral networks implicated in PTSD. The findings will be published in the journal Science on February 14, 2020. This study, which is sponsored by Inserm and led by Inserm researcher Pierre Gagnepain, shows that the untimely resurgence of intrusive images and thoughts in PTSD patients – a phenomenon long attributed to a deficiency of memory – is linked to a dysfunction of the brain networks that control memory. The researchers expect that these findings will lead to the identification of new treatment options for PTSD sufferers.

- Context: the 13-Novembre program

Unprecedented in their scale and violence, the terrorist attacks of November 13, 2015 sent shockwaves throughout French society. In their aftermath, the scientific community decided to act, to improve our understanding of the consequences of such a trauma and to improve the treatment options available to victims and their loved ones. A few days after the attacks, Alain Fuchs, then President of the CNRS, addressed the academic world and called upon researchers to come up with projects to tackle these challenges. He asked for all interested research teams to submit “proposals on any subjects capable of addressing the societal questions raised by the terrorist attacks and their consequences, and which open up avenues for new solutions – social, technical, and digital”.

The 13-Novembre transdisciplinary program was then launched by Inserm, CNRS and héSam Université[2]. One of its components “Étude 1000”, in which 1,000 volunteers are followed up over 12 years. Volunteers include people who were directly exposed to the violence – survivors and people close to the victims, members of the emergency response teams, residents of the neighborhoods targeted and of the Paris suburbs, as well as inhabitants of other French cities, in order to understand the construction and evolution of the memory of the attacks (see box).

The Remember project: understanding PTSD

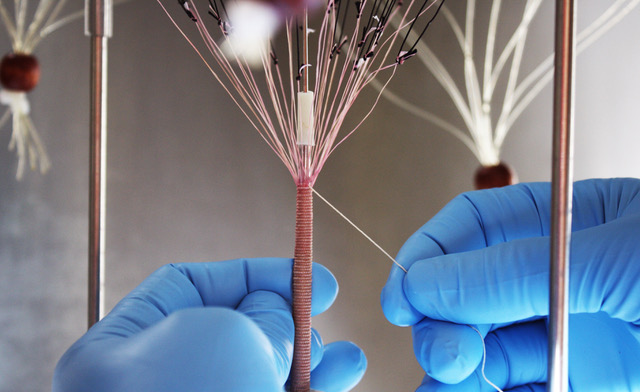

One of the components of 13-Novembre, the Inserm-sponsored project Remember makes it possible to go much further in the understanding of human memory. With this brain imaging study conducted in Caen on a subgroup of 175 participants, the researchers are exploring the effects of a traumatic event on brain structure and function, identifying neurobiological markers of both PTSD and resilience to trauma. They hope that one day this research will open up new avenues for treatment, to complement those already available.

As such, Remember is tackling a major question that has intrigued neuroscientists for years: why does PTSD affect some trauma victims but not others? One of the objectives of this study, published in the journal Science, is to determine whether there is a link between the control mechanisms of our memory and the individual capacity for resilience.

“We focused this research program on the protective factors and brain markers associated with resilience to trauma. This is what makes our work original compared with previous studies that focused more generally on the impact of trauma on memory and its dysfunction”, emphasizes Pierre Gagnepain, scientific leader of Remember.

“Étude 1000″

During four campaigns of filmed interviews initiated with the support of France’s Audiovisual Institute (INA) and Defense audiovisual communication and production unit (ECPAD), which are being conducted over a 10-year period (2016, 2018, 2021, and 2026), the participants are asked to share their accounts and evoke their personal memories of the attacks on the basis of an identical interview guide.

These individual accounts will then be analyzed in detail and put into perspective with the collective memory as it is constructed over the years, particularly within the media spaces (television and radio news, press articles, social networks, images of commemorations, etc.).

An approach inspired by that of William Hirst, Professor of Psychology at The New School (New York, USA), following September 11. Along with his teams, he collected some 3,000 written questionnaires of people affected by these attacks.

13-Novembre takes this methodology further by using video recordings, by seeking to follow the same people over the 10-year period, and by adopting a transdisciplinary approach. Seen like this, it is a world first. “With 13-Novembre, the idea was to take things even further thanks to a very rich collaboration among multiple disciplines and the implementation of the biomedical study Remember. A study that gives us the unique scientific opportunity to observe the process of individual memory construction and how it interacts with collective memory”, emphasize Francis Eustache and Denis Peschanski, codirectors of 13-Novembre.

- PTSD

PTSD can develop in people who have been confronted to shocking, dangerous or terrifying events. First identified and studied by scientists in servicemen and women returning from the front, it can affect anyone – children and adults alike. PTSD can develop following any type of trauma, such as a natural catastrophe, sudden death of a loved one or terrorist attack, such as those of November 13, 2015. Studies performed in the USA and Canada estimate a 6 to 9% prevalence of the disorder in the general population.

Intrusive memories a core component

PTSD is a complex condition characterized by symptoms that can vary from one person to another. It can occur just after the trauma or years later. It can remain silent for relatively long periods of time. One of the most characteristic symptoms is the frequent intrusion of memories of the images, smells and sensations linked to the trauma.

These intrusions, which severely impact everyday life, cause great distress as well as other intense emotions, such as fear, guilt, and anger. These can be accompanied by physical symptoms triggered by the recollection of the event, such as muscle tension or increased heart rate.

In order to minimize the distress caused by intrusive memories, sufferers of PTSD also have a tendency to develop avoidance behaviors in the face of any circumstances that could evoke memories of the trauma. These can involve refusing to think or talk about the event, or gradually withdrawing from society and even their loved ones.

- Understanding more about the cause of intrusive memories

According to the traditional models of PTSD, the persistence of painful intrusive memories is caused by memory dysfunction – a bit like a scratched record playing the same fragments of our memories over and over again. From the anatomical point of view, such dysfunctions are particularly visible in the hippocampus – a key region for the formation of memory.

In addition, patients’ attempts to suppress their traumatic memories have long been considered an ineffective mechanism. Instead of confronting these painful images in order to leave them in the past, the way they were trying to repress or drive them out was seen more as a negative strategy, intensifying the intrusions and worsening the situation of those with PTSD.

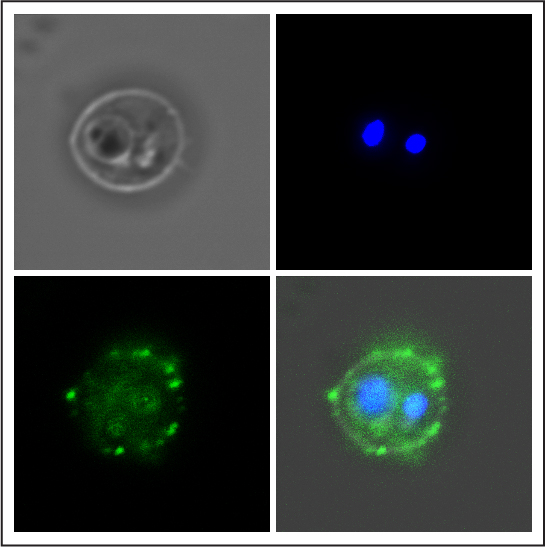

The brain imaging study published in the journal Science challenges some of these ideas, hypothesizing that the untimely resurgence of intrusive images and thoughts could also be linked to a dysfunction of the brain networks implicated in controlling memory (going back to the previous metaphor of the record player, the turntable arm is not working correctly). “These control mechanisms act like a regulator of our memory and are engaged in halting or suppressing the activity of the regions associated with memories, such as the hippocampus”, states Gagnepain.

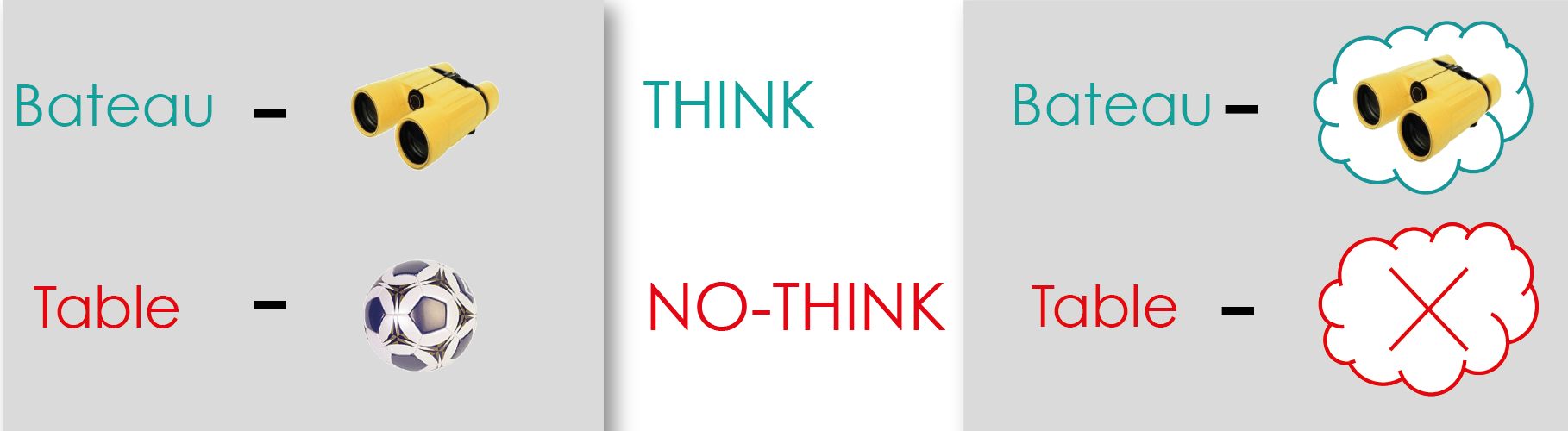

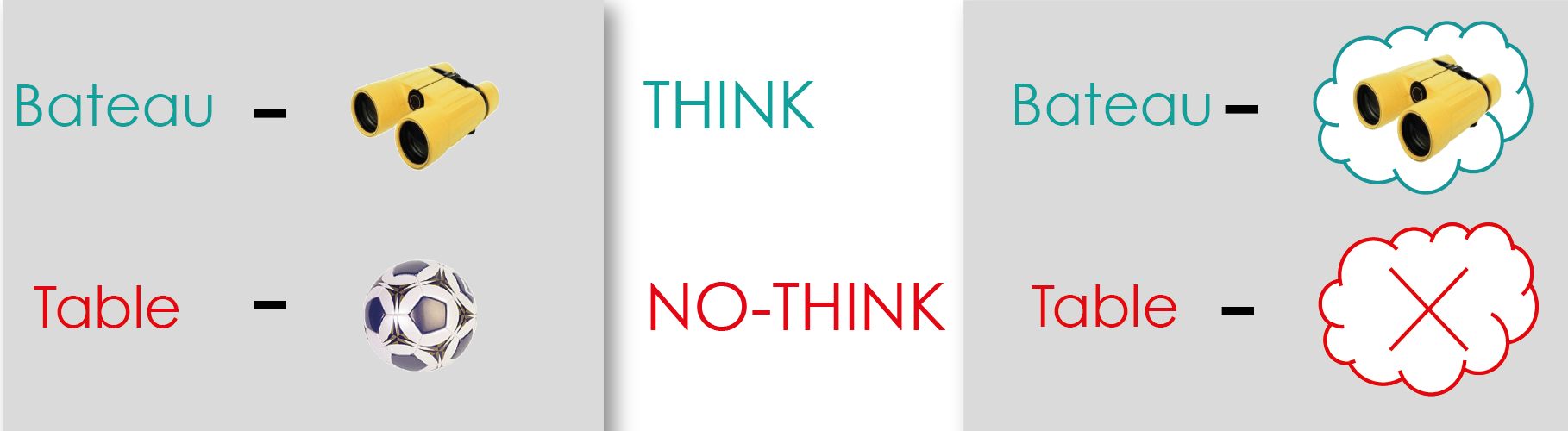

The participants had to perform the Think/No-Think task in the MRI machine.

Methods and results

Together with his colleagues, Gagnepain worked with 102 survivors of the Paris attacks, 55 of whom had PTSD. Also involved in the study were 73 people who had not been exposed to the attacks.

In order to model the resurgence of intrusive memories observed in the PTSD of these volunteers without putting them through the ordeal of viewing the shocking images of the attacks, the scientists opted for a brain imaging research protocol based on the Think/No-Think method (see box).

The aim of this method is to create associations between a cue word and an unrelated everyday object (for example, the word chair with the image of a ball), in order to reproduce the presence of an intrusion when confronted with the cue word. “Then we can study the capacity of the participants to drive and suppress from their mind the intrusive image that emerges against their will when confronted with the cue word”, says Alison Mary, researcher and co-author of the article.

The Think/No-Think method is used to obtain a model of memory intrusion (see box). Credits: Pierre Gagnepain

The Think/No-Think method

For the researchers, it was important not to expose survivors to new traumatizing images that could plunge them back into a state of distress. The Think/No-think paradigm models the situation of patients with PTSD, confronted with images and memories that frequently intrude on them, but without using potentially traumatic stimuli.

During the learning phase, the participants learn pairs of stimuli by heart (for example, the word chair associated with the image of a ball). The objective? When the word chair is subsequently presented to the participants, the image of the ball is automatically reactivated. The word chair acts as a cue for mental intrusion, triggering the associated memory of the ball. The emergence of this memory is spontaneous, simulating certain characteristics of the genuine intrusive memories of PTSD.

In the phase that follows, the brain activity of the participants is measured using functional MRI, according to two conditions:

· Think: one of the words is presented written in green and the subject has to visualize the associated image precisely.

· No-Think: one of the words is presented in red and the subject has to clear their mind and prevent the image from emerging, whilst maintaining their attention on the word. Here, researchers distinguish the situations in which the image does not emerge and those that lead to intrusion, even if the intrusion is brief. This means that they can observe the differences in brain activity in both cases, in order to closely study the memory control mechanisms used to repress an intrusive image.

Intrusive memory control and resilience

The researchers looked at the brain connections between the control regions located in the frontal cortex (at the front of the brain), and the memory regions, such as the hippocampus. They hoped to identify any differences among the three groups of participants (the first not exposed to the attacks, the second exposed but without PTSD, and the third also exposed but with PTSD).

The results show that the participants with PTSD present a deficiency of the mechanisms that suppress and regulate the activity of the memory regions during an intrusion (particularly the activity of the hippocampus).

Conversely, the functioning of these mechanisms is to a large extent preserved in the individuals without PTSD, who are able to fight the intrusive memories. “In our study, we suggest that the memory suppression mechanism is neither intrinsically poor nor responsible for the intrusions, as was previously believed. However, its dysfunction is. If we use the analogy of a car’s brakes, it is not the act of applying them – or in our case the act of suppressing the memories – that poses a problem, but the fact that the braking system is faulty, which leads to their overuse”, explains Gagnepain.

- Implications of this research

These findings will make it possible to challenge traditional thinking on PTSD and devise new avenues for treatment.

Scientific implications

Firstly, the study highlights that the persistence of the traumatic memory is probably not solely linked to a dysfunction of memory but also to a dysfunction of the memory control mechanisms.

Secondly, although the memory suppression processes in victims of PTSD have long been considered problematic and ineffective (because they enable the traumatic memories to return in an even more violent way), the study shows that the problem is not this mechanism as such, but its poor implementation by the cerebral networks.

Patients with PTSD are actually considered to be in an ongoing state of memory “suppression”, even when there is no memory intrusion, in order to compensate this deficient memory control system. It remains to be determined whether these control difficulties arise after the trauma or were present before, rendering the individual more vulnerable.

Therapeutic implications

Many of the current PTSD therapies are aimed at recontextualizing the problematic memories, at making the patients aware that these memories belong in the past, and at reducing the feeling of fear that they generate.

Designing new interventions which are disconnected from the traumatic events and which stimulate the control mechanisms identified in this study could be a useful addition in training patients how to implement more effective mechanisms of suppression. “The current treatments all involve confronting the trauma, which is not always easy for the patients. It could be imagined that this type of task stimulates the mechanisms of suppression, thereby facilitating the processing of the traumatic memory in the traditional therapies”, the researchers point out.

Findings in interaction with the other components of 13-Novembre

The study also makes it possible to improve research into the brain function of the “resilient” survivors who have not developed PTSD. “This study goes further than all the others, which traditionally focus on military personnel exposed to traumatic situations. However, their exposure has rarely been to the same extent, to the same situations, or at the same frequency. So it is often difficult to study in parallel PTSD sufferers and resilient individuals who have been exposed to the same horrifying situation. We have that possibility here and I hope the progress made will have major positive impacts on trauma victims worldwide”, emphasizes Gagnepain.

Several studies are now emerging in order to supplement these findings. The researchers will in particular use the data obtained from the brain imaging sessions to take a closer look at specific alterations of the hippocampus, a key structure in the expression of intrusive memories. Since these participants have already been studied on two occasions separated by a two-year interval, the researchers will also be able to study their individual evolution and try to identify biomarkers to predict it. “It will be interesting to compare the data from 13-Novembre, which studies the collective and individual evolution of traumatic memories, with those of Remember, which studies the brain mechanisms used to fight this trauma. This research is original and unprecedented on the global scale”, concludes Gagnepain.

It is this ability to bring so many disciplines into dialogue and explore the entire complexity of human memory that makes the 13-Novembre program so rich.

Participant accounts*

Alice’s story

For Alice and the father of her children, November 13, 2015 was meant to be a special day – their first romantic meal out since the birth of their second son. Living in the XI arrondissement, they had chosen a local restaurant. Just after their meal was cut short by the babysitter because their youngest child was sick, and just after they decided that Alice would go and see to him, there was an explosion in the Comptoir Voltaire café across the road. Assuming a gas leak in one of the nearby buildings, Alice had no idea what was actually happening.

It was only when she was climbing the stairs to her apartment, whilst the news of the attacks was making the tour of the globe, that Alice began to realize what she had experienced. For her, the rest of the night was associated with a floating, anxious sensation while her husband, gone to join colleagues for a wrap party, found himself confined at the party location. This sensation was followed by incomprehension in the face of the horror throughout the weekend that followed.

The week following the attacks was hard. Alice had difficulty realizing what had happened, she cried a lot. Every day, she feared for the lives of her children, who were attending schools in the neighborhood. She was rapidly diagnosed with PTSD.

Participation in the studies

One year after the attacks, Alice heard of an enrolment campaign conducted at the INA, which was looking for volunteers to take part in the Inserm and CNRS 13-Novembre program. Encouraged by her psychologist, by a desire to better understand the events of that evening and by a wish to share her account with the scientific community, she went along. Everything then fell into place, with Alice also accepting to participate in the program’s brain imaging study sponsored by Inserm, Remember.

For Alice, taking part in a biomedical study has been a very intense but enriching human experience. “In Caen, the team welcomed me with a great deal of kindness. A team of doctors and psychologists was there to ask questions about my health and to explain the protocol and its objectives. I was exhausted when I left: learning the word list was not easy and doing the Think/No-Think task in the MRI machine was difficult because of the noise. But I was well looked after and happy to know that my participation has helped to improve knowledge of brain functioning in PTSD”, she explains.

Alice has continued to make progress with the support of a psychologist whom she met at a crisis unit at the XI arrondissement city hall. She is happy to have been able to participate in Remember and hopes that its findings will serve to improve the treatment of people living with PTSD, and to make the disorder less alarming.

Dominique’s story

It was at a meeting of an association for the victims of the attacks that Dominique first heard about the 13-Novembre program codirected by Francis Eustache and Denis Peschanski. A survivor of the Parisian café attacks, Dominique has always had a strong interest in science, particularly in the major challenge that represents exploring the human brain to elucidate its mysteries. The transdisciplinary aspect of the program – at the crossroads of social and neurosciences – as well as the researchers’ desire to study the construction of memory, aroused his curiosity.

“As a survivor of the attacks, you feel a kind of guilt. I wanted to do something, I wanted to help move things forward after these events. Participating in a scientific study with such important themes as the collective memory of a country, the treatment of victims with PTSD, and coming together as a society after the attacks were important to me. And what is more, I felt capable of doing it”, he explains.

After participating in the 13-Novembre program filmed INA sessions, Dominique then accepted to go to Caen twice as a volunteer in Remember. An experience that was both difficult and highly enriching. “The discussions with the various researchers were fascinating, I had lots of questions about their work, about what they were looking for in the brain. However, the MRI part was a real challenge. While I am not claustrophobic, it is still a narrow space with little light, and the machine is very noisy, producing sounds that can evoke gunshots. It is very hard when you are trying to fight your intrusive memories. But I was well looked after by the team”, he specifies.

In order to conquer the MRI step during his second session in Caen, Dominique had practiced being in confined spaces by spending time under his bed at home. However, to his great surprise, the second session went without incident. He is ready to return to Caen next year for the third and final series of experiments in order to collect additional data for studying the longer-term evolution of the study participants, and to build on the study published in Science.

* Names were changed at the request of participants

[1] Currently at the European Centre of Sociology and Political Science of the Sorbonne (CNRS/Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne/EHESS)

[2] With the scientific component driven by the CNRS and Inserm and the administrative component by héSam Université, 13-Novembre is funded by the French Secretary General for Investment via the French Research Agency (ANR) as part of the Investments for the Future program (PIA). It has 31 partners and the support of 26 entities. It is a component of the facility of excellence, MATRICE. For more information: http://www.memoire13novembre.fr/partenaires-et-soutiens

Resilience after trauma: the role of memory suppression