Aspartame, a well-known artificial sweetener, is for example present in thousands of food products worldwide. © Mathilde Touvier/Inserm

Artificial sweeteners are used to reduce the amounts of added sugar in foods and beverages, thereby maintaining sweetness without the extra calories. These products, such as diet sodas, yoghurts and sweetener tablets for drinks, are consumed by millions of people daily. However, the safety of these additives is the subject of debate. In order to evaluate the risk of cancer linked to them, researchers from Inserm, INRAE, Université Sorbonne Paris Nord and Cnam, as part of the Nutritional Epidemiology Research Team (EREN), analyzed data relating to the health of 102,865 French adults participating in the NutriNet-Santé cohort study and their consumption of artificial sweeteners. The results of these statistical analyses suggest a link between the consumption of artificial sweeteners and an increased risk of cancer. They have been published in PLOS Medicine.

Given the adverse health effects of consuming too much sugar (weight gain, cardiometabolic disorders, dental caries, etc.), the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends limiting free sugars1 to less than 10% of one’s daily energy intake2. Therefore, in order to ensure that foods maintain that sweet taste so sought after by consumers worldwide, the food industry is making increasing use of artificial sweeteners. These are additives that reduce the amount of added sugar (and calories) without reducing sweetness. What is more, in order to enhance flavor, manufacturers use them in certain products that traditionally contain no added sugar (such as flavored potato chips).

Aspartame, a well-known artificial sweetener, is for example present in thousands of food products worldwide. While its energy value is similar to that of sugar (4 kcal/g), its sweetening power is 200 times higher, meaning that a much smaller amount is needed to achieve a comparable taste. Other artificial sweeteners, such as acesulfame-K and sucralose, contain no calories at all and are respectively 200 and 600 times sweeter than sucrose.

Although several experimental studies have pointed to the carcinogenicity of certain food additives, there are no robust epidemiological data supporting a causal link between the everyday consumption of artificial sweeteners and the development of various diseases. In a new study, researchers sought to examine the links between the consumption of artificial sweeteners (total and most often consumed) and the risk of cancer (global and according to the most common types of cancer) in a vast population study. They used the data provided by 102,865 adults participating in the NutriNet-Santé study (see box below), an online cohort initiated in 2009 by the Nutritional Epidemiology Research Team (EREN) (Inserm/Université Paris Nord/CNAM/INRAE), which also coordinated this work.

The volunteers reported their medical history, sociodemographic data and physical activity, as well as information on their lifestyle and health. They also gave details of their food consumption by sending the scientists full records of what they consumed over several 24-hour periods, including the names and brands of the products. This made it possible to accurately evaluate the participants’ exposure to additives, and more particularly to artificial sweeteners.

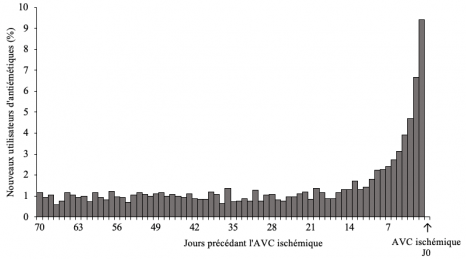

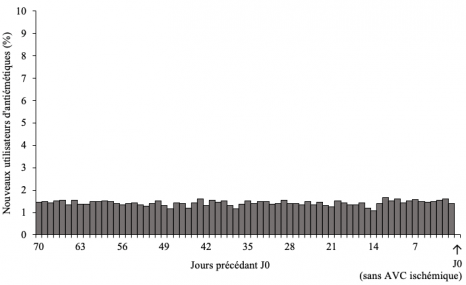

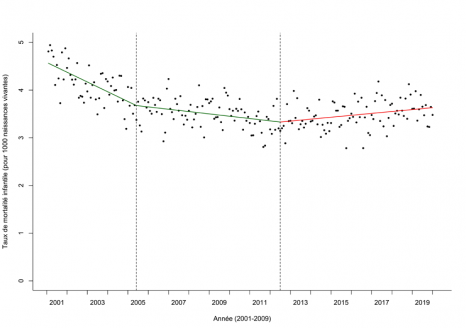

After collecting information on cancer diagnoses over the NutriNet-Santé study period so far (2009-2021), the researchers conducted statistical analyses in order to study the links between the use of artificial sweeteners and the risk of cancer. They also took into account various potentially confounding factors, such as age, sex, education, physical activity, smoking, body mass index, height, weight gain over the study period so far, family history of cancer, as well as intakes of energy, alcohol, sodium, saturated fatty acids, fiber, sugar, whole grain foods and dairy products.

The scientists found that compared with those who did not consume artificial sweeteners, those who consumed the largest amounts of them, especially aspartame and acesulfame-K, were at increased risk of developing cancer, irrespective of the type.

Higher risks were observed for breast cancer and obesity-related cancers.“In accordance with several in vivo and in vitro experimental studies, this large-scale, prospective study suggests that artificial sweeteners, used in many foods and beverages in France and throughout the world, may represent an increased risk factor for cancer,” explains Charlotte Debras, PhD student and lead author of the study. Further research in other large-scale cohorts will be needed in order to replicate and confirm these findings.

“These findings do not support the use of artificial sweeteners as safe alternatives to sugar, and they provide new information in response to the controversy regarding their potential adverse health effects. They also provide important data for their ongoing re-evaluation by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and other public health agencies worldwide,” concludes Dr. Mathilde Touvier, Inserm Research Director and study coordinator.

NutriNet-Santé is a public health study coordinated by the Nutritional Epidemiology Research Team (EREN, Inserm / INRAE / Cnam / Université Sorbonne Paris Nord) which, thanks to the commitment and loyalty of over 170,000 participants (known as “Nutrinautes”), advances research into the links between nutrition (diet, physical activity, nutritional status) and health. Launched in 2009, the study has already given rise to over 200 international scientific publications. In France, new participants are currently being encouraged to join in order to continue to advance research on the relationship between nutrition and health.

By devoting a few minutes per month to answering various online questionnaires relating to diet, physical activity and health, participants contribute to furthering knowledge of the links between diet and health. With this civic gesture, we can each easily participate in research and, in just a few clicks, play a major role in improving the health of all and the wellbeing of future generations. These questionnaires can be found on the secure platform www.etude-nutrinet-sante.fr.

1 Sugars added to foods and beverages and sugars naturally present in honey, syrups, and fruit juices.

2 World Health Organization, 2015