©AdobeStock

In humans, “Theory of Mind” is the ability to understand others’ mental states: what they think, what they feel, what they desire, what they love, etc. It plays a major role in human social interactions.

But where did this ability evolve from? What type of selection pressure ultimately led to this being imparted on the human species?

In order to offer a response, Jean Daunizeau, Inserm Researcher within ICM, Shelly Masi (National Museum of Natural History, MNHN) and her colleagues first developed a means of measuring the level of sophistication of theory of mind, based on behavioral analysis in simple interactive games. After validating this method in humans, they then used it to compare the level of sophistication of theory of mind in seven non-human primate species, from lemurs to the great apes (gorillas, orangutans, and chimpanzees).

Their study is the first to provide data on the origins of human social intelligence. In particular, the results of the study go against the generally accepted hypothesis, which stipulates that theory of mind developed in response to problems arising from the complexity of the social group in which animals evolved.

It appears rather that the evolution of theory of mind was primarily determined by limiting neurobiological factors, such as brain size.

Lastly, the researchers identified a large difference, an evolutionary “gap“, between the capacity of theory of mind in the great apes and humans. This research has been published in PLOS Computational Biology

© Fotolia

The way in which people make decisions can sometimes seem reckless or even totally irrational. One explanation for this behavior is that humans tend to prefer information that confirms their beliefs and overlook that which contradicts them. This is a phenomenon called confirmation bias.

In recent research published in PLoS Computational Biology, a team of researchers led by Stefano Palminteri and Sarah-Jayne Blakemore tested 20 subjects by having them choose between two symbols, each worth a different number of points. The aim was to get as many points as possible. The results of this study show that the participants won more points when their choice was followed by feedback. In addition, it was all the more effective when the feedback was positive (“Your choice is the best”) rather than negative (“You would have got more points with a different choice”). This confirmation bias slowed the subjects’ ability to adapt to change to such an extent that it affected the total number of points won by the most biased of the subjects. In conclusion, people preferentially take into account information that confirms rather than contradicts their choices.

According to Stefano Palminteri: “These results may explain why people maintain false beliefs or persist with risky health behaviors, despite obvious information to the contrary. On the other hand, this bias may also enable certain people to maintain motivation and self-esteem.” Knowing more about the biases in our learning could mean that we learn more effectively and are more aware of our natural inclination to jump to conclusions.

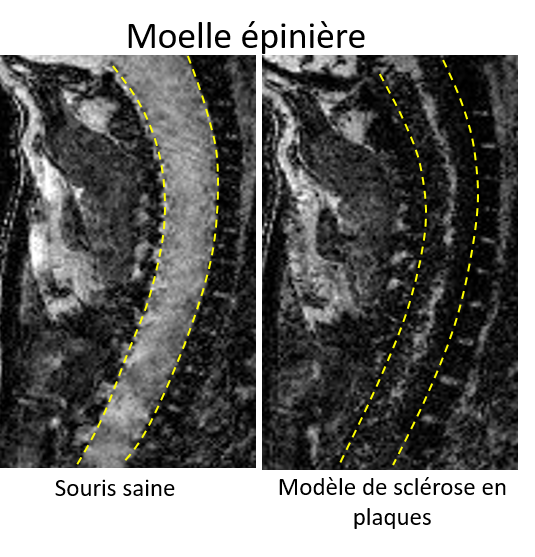

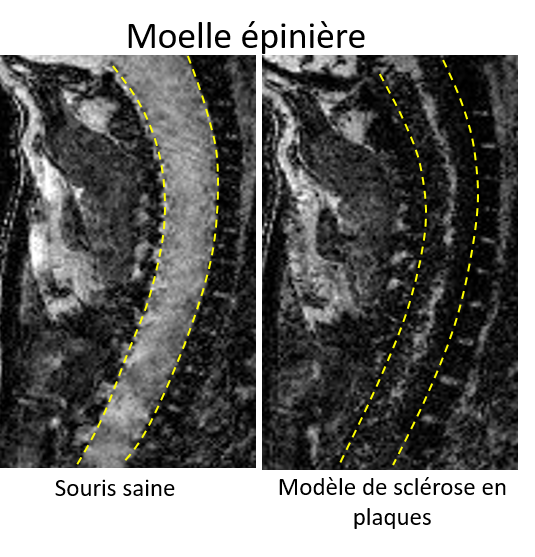

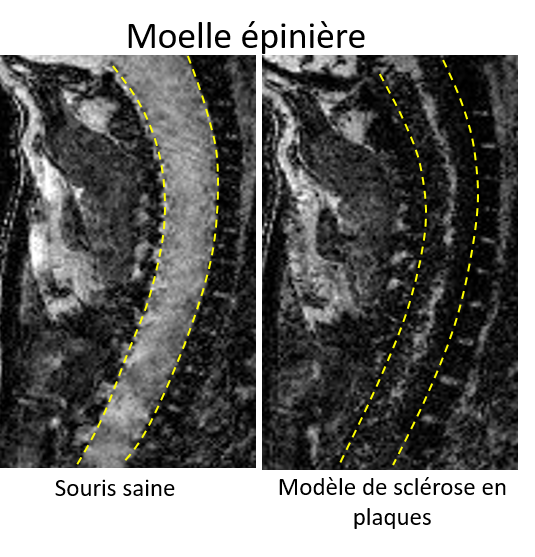

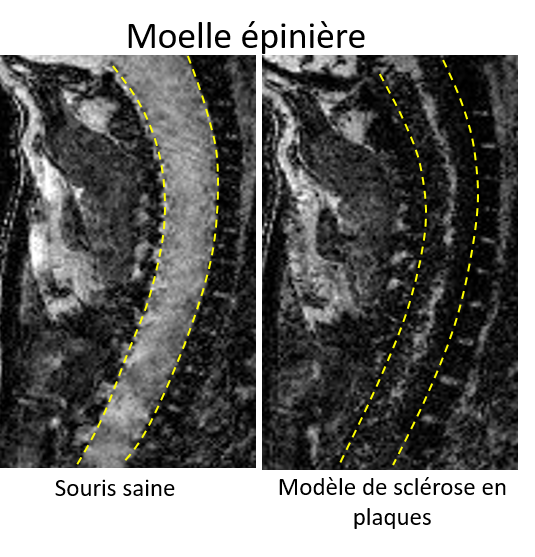

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune inflammatory disease of the central nervous system. It generally affects young people, in whom it is the leading cause of non-traumatic motor disability. This disability develops either progressively or in the form of relapses interspersed with periods of remission.

At present, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is widely used to diagnose and follow up patients with MS. However, no imaging tools exist to predict the onset of relapse.

MS is caused, at least partially, by inflammatory cells (notably lymphocytes) migrating into the brain and spinal cord through the walls of blood vessels. The cells migrate by binding to adhesion molecules that are present on the surface of these vessels.

Researchers from the “SpPrIng” team, led by Fabian Docagne at Inserm Unit 1237 in Caen, France, have developed an MRI technique in which the progression of the disease can be followed in space and time in a mouse model of MS. To do this, they used MRI-detectable iron beads that bind to the adhesion molecules.

In this study, published in the journal PNAS, the authors demonstrate that this technique is able to visualize the migration of the inflammatory cells, thereby making it possible to predict the onset of relapse in asymptomatic mice, and remission in sick mice.

This technique could in the future be adapted for use in humans to improve prognosis and follow-up in patients with MS.

In the right-hand image, the iron beads (in black) have entered the spinal cord, thus revealing inflammation

© Fotolia

Depression is not just one of the world’s most incapacitating illnesses – it also comes with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, particularly that of the coronary arteries (angina and heart attack).

According to a study by Inserm conducted in 10,000 people followed up for more than 20 years, this risk is doubled in non-executive or blue-collar workers in relation to executives. These data come from GAZEL, a French cohort of former employees of what at the time was known as Électricité de France-Gaz de France (EDF-GDF), and have been analyzed by a multi-disciplinary team of psychiatrists, epidemiologists, and cardiologists. The depressive symptoms were measured in 1993 and then each cardiac event occurring during the follow-up period was carefully validated by a committee of experts.

This study shows that the lower the socioeconomic status of a depressed individual, the greater their associated cardiac risk. It also shows that this risk cannot be explained by health behaviors such as smoking or physical activity, thereby suggesting that depression could have a direct impact on cardiovascular health.

It remains to be understood why these mechanisms are more pronounced in non-executive or blue-collar workers than in executives. One plausible interpretation is an increased reactivity to stress when socioeconomic status is perceived to be low, as illustrated by certain neuroscientific studies. In any case, these results call for particularly close attention to be paid to the cardiovascular health of individuals with depression, and even more so in those with other psychosocial difficulties.

©Inserm

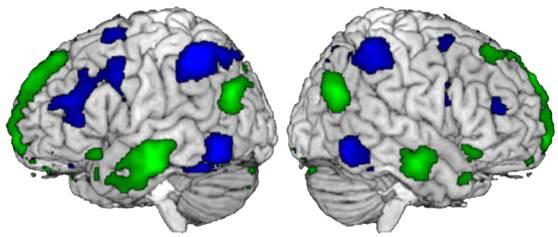

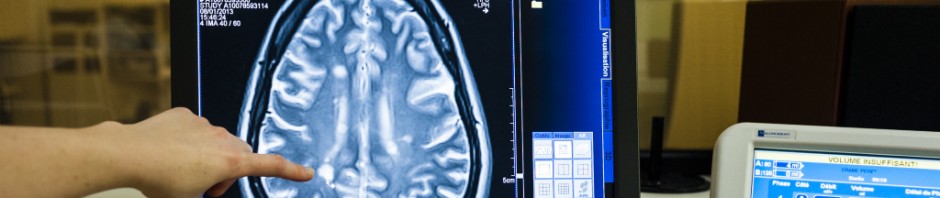

Predicting recovery from coma following cardiac arrest remains a question to which physicians do not have an exact response. When – and if – a critical care patient will recover consciousness is evaluated essentially by means of recurrent clinical examinations and the recording of brain activity. Researchers at Inserm (Inserm Unit 1214 Toulouse NeuroImaging Center) led by Stein Silva, have recently developed a method that uses magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to predict such recovery. The results were published this month in Critical Care Medicine.

Coma is a state of prolonged unconsciousness during which the patient fails to respond to any stimuli, including pain. There are many possible causes of coma. It can, for example, be brought on by temporary loss of blood flow (ischemia) or oxygen (anoxia), both of which are essential for the brain to function. This scenario, which is seen with cardiac arrest, is one of the leading causes of coma both in France and worldwide. The disruption in blood flow brought on by the cardiac dysfunction leads to major and extensive aggression of the brain tissues: the gray matter, consisting mainly of nerve cell bodies (neurons), and the white matter, formed from the nerve fibers of these neurons. In this study, Stein Silva’s team explored the following idea: does cardiac arrest impact brain structure? If so, is the potential for neurological recovery from coma related to the degree and extent of this impact?

To study this hypothesis, the researchers used MRI to measure and then compare the volume of gray matter in comatose post-cardiac arrest patients and healthy subjects. Measurements were made of the gray matter in the cerebral cortex and in the sub-cortical structures located deeper in the brain, a few days after the cardiac arrest. The results show that precise quantification of the volume of gray matter in the brain revealed early and extensive brain atrophy in these patients. However, above all, these data indicate that the degree of this atrophy, measured several days after the onset of the cardiac arrest, is indeed associated with the potential for neurological recovery of patients, evaluated one year after the start of the coma. The greater the atrophy, the lower the chance of a favorable outcome for the patient. Finally, when going into greater detail, this research is in favor of the existence of key brain regions, whose anatomical integrity appears to be associated with the capacities to form conscious processes.

All in all, these results shed new light on the biological mechanisms necessary for the creation and maintenance of consciousness in humans. According to Stein Silva: “this research opens new avenues for evaluating the prognosis of these patients and means that we can consider innovative therapies focused on the protection and specific modulation of certain brain structures involved in the emergence of consciousness following cardiac arrest.”

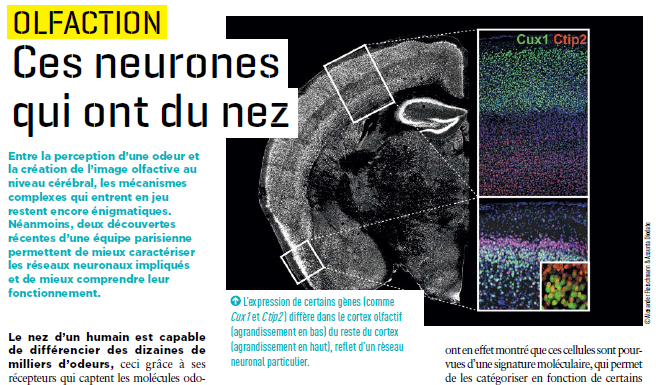

Thanks to the receptors in our nose, we can identify thousands of smells. But there are still many grey areas regarding the mechanisms at work in sending information to the brain. Research conducted by Alexander Fleischmann and his colleagues at Unit 1050, “Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Biology” (Collège de France/CNRS/Inserm) provides a better understanding of the neural networks activated when an odour is perceived.

Issue 32 of Science&Santé magazine devotes an article to this discovery.

(c) Fotolia

Between now and 2050, the number of people aged over 60 years is set to double according to estimates by the World Health Organisation, thus going from 65 million to 2 billion. Seniors may then represent 22% of the world population in 2050.[1] In this context, prevention and encouraging people to “age well” constitutes a primary challenge for our societies.

In an attempt to respond to this problem, the research programme Silver Santé Study was launched in January 2016. This European project, coordinated by Gaël Chételat at Inserm Caen, is aimed at evaluating the impact of meditation on the well-being and mental health of older people.

A first clinical trial will be conducted in four countries to study the effects of meditation on patients at a high risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Meanwhile, a second trial will be conducted only in Caen, on two groups:

– A group of expert meditators aged over 65 years, with over 10,000 hours of practice, in order to determine the mechanisms of action by which meditation might prevent ageing,

– A group of people aged over 65 years without cognitive impairment. 126 participants will be monitored for 18 months, randomly divided into three groups: the first will follow a meditation programme developed as part of the project and appropriate for this population; the second will follow an English language learning programme, and the third group will have no intervention. Tests done prior to the study and after 18 months of monitoring will allow the effects of the two mental interventions to be assessed. The initial results of the study will be known in late 2019.

Inserm is looking for volunteers aged over 65 years, based in Caen and the surrounding area, to participate in this study. Information sessions will be held on 8 October and 22 October 2016 in PFRS Caen, and a participation form is available at the following address: https://silversantestudy.fr/. If you have any questions, you may contact Gaël Chételat, Inserm Research Director, and coordinator of the study.

[1] Source: WHO

(c) Fotolia

According to a few studies, when their brain suffers from a lack of oxygen, babies born by caesarean section are more likely to develop some mental disorders including schizophrenia. Researchers from Inserm compared two populations of patients with schizophrenia – delivered vaginally or by caesarean section – in order to determine the particular characteristics associated with type of delivery.

The study was conducted on 454 patients (with a mean age of 32 years) who consulted the Expert Centre for Schizophrenia, 11% of whom had been born by caesarean section.

The researchers did not find any links between type of delivery and the characteristics of the disease: age of onset, severity, or response to treatments. However, they observed lower intellectual functioning in schizophrenic patients born by caesarean section, suggesting a link with “neurodevelopmental” schizophrenia, where the disease may be due to an impairment of brain maturation.

Conversely, patients born by caesarean section had less peripheral inflammation than subjects delivered vaginally. However, it had previously been shown that peripheral inflammation, a natural response of the body to stress, may become chronic in people with schizophrenia, and lead to more serious cognitive disorders.

This paradox might be explained by the fact that these patients have a different intestinal microbiota from subjects delivered vaginally, something that has been observed in several studies. Future studies, by analysing the profile of microbiotas, will assess whether the bacterial composition of the digestive tract may influence the weight or intellectual functioning of patients suffering from schizophrenia.

A wide range of compounds is on the market to ameliorate depressive symptoms, however their efficiency is achieved only after long periods of treatment and not in 100% of patients. Inserm researchers identified early cellular changes in the brain for the emergence of depressive symptoms, and a novel promising drug target.

These results are published in the journal Nature Medicine on Janaury 25th, 2016.

The aim of Manuel Mameli, Inserm researcher and Dr. Salvatore Lecca in his team, at Inserm Unit 839 the “Institut du Fer a Moulin (IFM)” (Inserm/UPMC), was to understand the initial cellular modifications occurring after a stressful aversive experience. Protracted stress and aversive experiences are indeed a trigger to engage depressive behaviors in animals and humans.

Using electrophysiological, viral-based and pharmacological approaches researchers found that the activity of neurons located in the lateral habenula – a cerebral nucleus for aversion and disappointment – increased after a stressful experience due to a reduced function of two proteins controlling neuronal function (GABAB and GIRK).

Inserm scientists designed a rescue strategy that reversed the cellular modifications and ameliorated depressive symptoms after aversive experience by targeting a specific phosphatase (PP2A). By employing a rodent model of mood disorders (Learned Helplessness), that recapitulates a number of behavioral phenotypes typical of human depression, they have shown that the inhibition of PP2A was efficient to rapidly ameliorate the behavioral phenotype of mice.

“Our study unravels unknown early cellular mechanisms able to trigger complex behavioral responses. Our study further highlights the role of the lateral habenula in the aetiology of depression. Our results provide insights on a novel potential pharmacological target that could be studied for a therapy of mood disorders”

explain Manuel Mameli, Inserm researcher.

Depression is a real public health issue with 8% of adolescents affected by it, according to the French National Authority for Health (HAS). Adolescence is a time of transition during which young people are prone to episodes of depression. This often complicates the diagnosis of this disease.

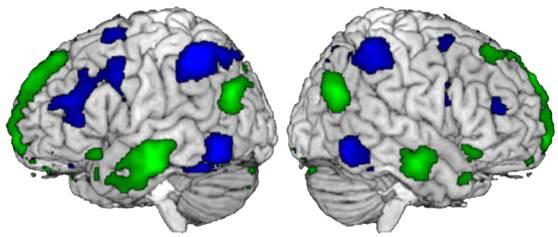

According to some studies, adolescents with severe depression appear to have deviations in the areas of the brain associated with reward response. It may explain that lack of interest and moroseness are more common symptoms than sadness.

To better understand this phenomenon, researchers at Inserm Unit 1000 “Neuroimaging and Psychiatry”, led by Jean-Luc Martinot, in collaboration with a team from King’s College (London) have studied over 1,500 young people (at 14 years old and two years later) using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) through the European study IMAGEN. Participants were split into three groups: one group with depression, a second group with isolated symptoms of depression with no actual diagnosis and finally, a group of healthy subjects

Each participant had to carry out a task where the brain’s reward response could be assessed (winning points in a game). The results of the simulated MRI confirms the scientists’ hypothesis—that adolescents with depression or occasional symptoms of depression have reduced activity in a specific area of the brain, the ventral striatum, which is involved in the reward circuit. It is significant that the response in this region is even weaker than the depressed person’s lack of interest.

“The low activity in this region detected in healthy adolescents at 14 years old is correlated with the onset of depression or symptoms of depression at age 16”, explains Jean-Luc Martinot, Research Director at Inserm.This study shows that impaired reward circuitry function is a factor that renders adolescents vulnerable to depression. The detection of symptoms involving loss of interest in adolescents and taking them into account in the early stages may help predict the onset of the disease or relapse and, as such, enable targeted early intervention well in advance.