The final conclusions of the JIKI clinical trial, testing the efficacy of favipiravir in reducing mortality in individuals infected by Ebola virus in Guinea, are published in PLoS Medicine this week. This work was carried out under the leadership of Prof. Denis Malvy, Inserm, with the help of a large team of international researchers. Although the conclusions are qualified, they have nonetheless made it possible to collect data and benchmarks that will enable researchers to base their future trials on robust hypotheses and criteria.

Ebola fever is an extremely lethal disease, for which there is no proven effective treatment. In September 2014, at the height of the epidemic, the World Health Organisation released a shortlist of drugs suitable for studies on Ebola virus (EBOV) disease, including favipiravir, an antiviral drug developed for the treatment of severe forms of influenza. An international team under the auspices of Inserm carried out a study called JIKI (meaning “hope” in the Malinke language) in Guinea. The goal of the study was to test the feasibility and acceptability of an emergency trial carried out during a large epidemic of Ebola virus disease, and to collect preliminary data on the safety and efficacy of favipiravir in reducing mortality and viral load in patients with Ebola virus disease. Because of the exceptional circumstances of the recent epidemic of Ebola fever, the study was a pilot, proof-of-concept, non-randomised, multicentre trial, with a so-called historical comparator group, in which 126 participants received favipiravir in addition to standard basic care.

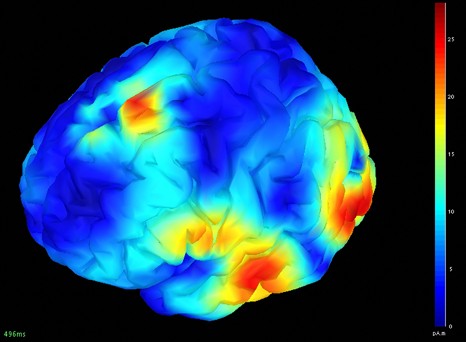

According to the results of the study, it is unlikely that favipiravir monotherapy is effective in patients presenting with very high viraemia, but the drug deserves continued evaluation in patients presenting with intermediate to high viraemia. This conclusion is based on two results—the mortality rates observed, and the dynamics of the EBOV RNA load during treatment.

In patients presenting with very high viraemia, mortality was 7% higher than the pre-trial value, and the viral load did not decrease. This suggests that a future trial is unlikely to demonstrate any benefit of favipiravir in these patients

In patients with lower viraemia, mortality was 33% lower than the pre-trial value, and the viral load decreased rapidly with treatment. The trial was non-randomised, and the 95% confidence interval included the pre-trial value. As a result, the present findings do not prove that favipiravir was effective in these patients, but they do suggest that the question remains open, and provide an indication on how to better address it.

The authors conclude, “In the middle of a health crisis such as an epidemic of Ebola fever, researchers can be faced with a situation in which random assignment of patients to groups receiving standard care or standard care plus an experimental treatment is not acceptable from an ethical point of view. In these rare circumstances, it may be decided not to conduct a trial, but to wait for more favourable circumstances, or to conduct a non-randomised trial. In this pilot experiment, we chose this second option. Our conclusions are qualified. On the one hand, we cannot draw conclusions on the efficacy of the drug, and our conclusions regarding tolerance, although encouraging, cannot be as definite as they would have been with randomisation. On the other hand, we have learned a great deal on how to define and conduct a trial under such unusual circumstances, working closely with the community and non-government organisations. We incorporated research work on care, so that care can be improved; we rapidly generated interim data useful in designing studies on Ebola fever, and shared them with the scientific community; and we collected evidence enabling researchers to base their future trials on solid preliminary hypotheses and criteria.”