Researcher Contact

Johan Garaude

Inserm researcher

ImmunoConcEpT, 1303 Inserm/5164 CNRS/University of Bordeaux

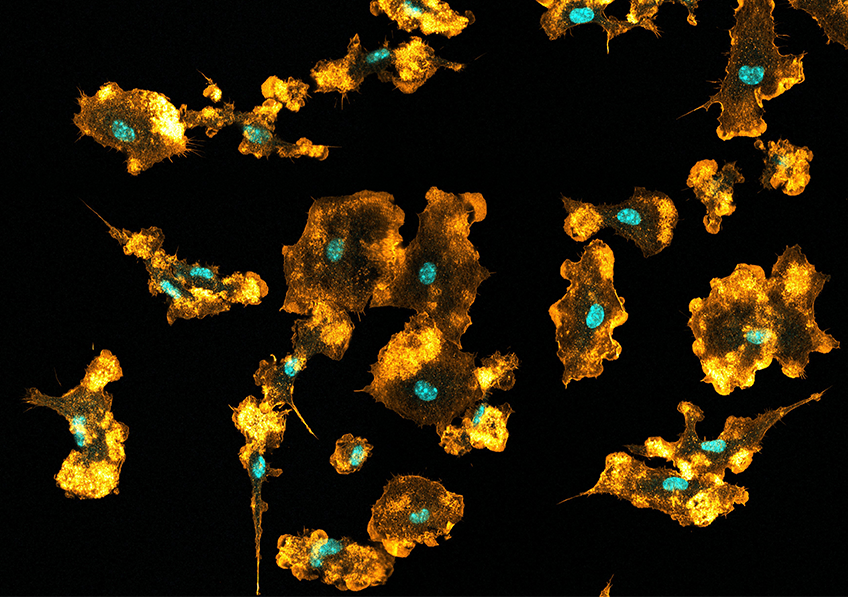

Mouse macrophages visualized using confocal microscopy, showing the nuclei (blue) and the actin network (orange). © Mónica Fernández Monreal, Bordeaux Imaging Center

Mouse macrophages visualized using confocal microscopy, showing the nuclei (blue) and the actin network (orange). © Mónica Fernández Monreal, Bordeaux Imaging Center

Macrophages, key cells of the immune system, play a central role in cleaning the body by ingesting and destroying pathogens (bacteria, viruses, etc.) and damaged cells. Scientists from Inserm, CNRS and the University of Bordeaux, in collaboration with international teams, reveal that this well-known role is accompanied by another surprising ability: in order to support their activity and metabolism, macrophages are capable of sourcing nutrients directly via the breakdown of the ingested bacteria. This research, to be published in Nature, also shows that macrophages extract nutrients more effectively from dead bacteria than from living bacteria. These findings shed new light on the fate of the pathogens ingested by macrophages and open up new avenues for the development of innovative vaccines and antibiotics.

Nutrients are essential molecules for the body to produce energy, maintain its metabolism, and ensure its growth and development. They participate in the activation, functioning and differentiation of immune cells. Among the latter, macrophages are innate immune cells that contribute to the maintenance and correct functioning of the body’s tissues. To do this, these immune players are able to ingest various large particles, debris and pathogens, ranging from damaged or aged cells to bacteria and viruses, and break them down by digesting them; a phenomenon called “phagocytosis”.

While most mammalian cells consume nutrients from food, some have additional abilities that enable them to seek nutrients through alternative processes. For example, previous studies have shown that certain phagocytes[1] are able to extract nutrients from the dead cells they digested. However, until now, scientists did not know whether this particularity applied only to the phagocytosis of the body’s own cells, or whether it could also work to extract nutrients from phagocytosed pathogenic organisms (bacteria, viruses, etc.).

An international research group co-led by Johan Garaude, Inserm researcher in the Conceptual, Experimental and Translational Immunology – ImmunoConcEpT unit (Inserm/CNRS/University of Bordeaux), has studied the phagocytosis of bacteria by macrophages and its potential role in macrophage metabolism.

With this in mind, the scientists compared macrophage metabolism in different environments: in the presence of living bacteria, dead bacteria, and in the presence of a component of the membrane of these bacteria that is well-known for activating macrophages.

Their findings show that those macrophages having phagocytosed whole bacteria, whether living or dead, presented a very different metabolic activity linked to the use of nutrients than those activated only by the component of the bacterial membrane.

“This suggests that the role of the macrophages could go far beyond the detection and simple destruction of bacteria, analyzes Garaude: they appear capable of exploiting them as a source of nutrients to support their own metabolism and thereby fulfil the specificity of their role as immune system alarm.”

The research team has also shown that the effectiveness of this metabolic recycling depends on the viability of the bacteria. Dead bacteria prove to be more efficient resources than living bacteria: the macrophages having internalized dead bacteria presented better transport and use of the nutrients derived from their breakdown. Thus, those having phagocytosed dead bacteria had much better chances of surviving in nutrient-depleted environments, unlike those having phagocytosed living bacteria.

“This difference could constitute an advantage for the survival of macrophages in infected tissues, when nutrients are scarce because they are already consumed by rapidly reproducing bacteria,” explains Garaude.

The study shows that this differentiated mobilization of nutrients is orchestrated by a mechanism internal to macrophages[2]. A mechanism that is thought to have the role of restricting the removal of nutrients by the macrophage during the phagocytosis of a living bacterium. It could also limit the excessive accumulation of nutrients within the macrophage, when it is having to simultaneously digest a large number of bacteria.

“This could be a protective mechanism to prevent macrophages from using potentially dangerous molecules, derived from infectious agents, or to regulate the intensity of the inflammatory response to infection by limiting access to nutrients that could ‘boost’ it,” adds Juliette Lesbats, doctoral student from the University of Bordeaux and first author of this research.

“Our findings highlight the capacity of phagocytes to adjust their cell metabolism to the ‘nutrient potential’ represented by phagocytosed bacteria, explains Lesbats. They show how, when combined with the capacity to detect microbial viability, this ability makes it possible to regulate the metabolic adaptation of immune cells.” Although the importance of this mechanism in bacterial infections has yet to be explored, this study opens up promising new avenues for fighting antibiotic resistance or devising new vaccine approaches.

[1] Cells capable of phagocytosis.

[2] This concerns the mTORC1 intracellular signaling pathway.

Johan Garaude

Inserm researcher

ImmunoConcEpT, 1303 Inserm/5164 CNRS/University of Bordeaux

Macrophages recycle phagocytosed bacteria to fuel immunometabolic responses

Nature

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08629-4

Juliette Lesbats1, Aurélia Brillac1, Julie A. Reisz2,$, Parnika Mukherjee3,$, Charlène Lhuissier4, Mónica Fernández-Monreal5, Jean-William Dupuy6,7, Angèle Sequeira4, Gaia Tioli1,8, Celia De La Calle Arregui9, Benoît Pinson10, Daniel Wendisch3, Benoît Rousseau11, Alejo Efeyan9, Leif. E Sander3,12, Angelo D’Alessandro2, and Johan Garaude1,4,*

1 University of Bordeaux, Inserm, MRGM, U1211, F-33000 Bordeaux, France.

2 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, United States of America

3 Department of Infectious Diseases, Respiratory Medicine, and Critical Care, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany, Corporate member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Berlin, Germany

4 ImmunoConcEpT, CNRS UMR 5164, Inserm ERL 1303, University of Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France

5 Université de Bordeaux, CNRS, Inserm, Bordeaux Imaging Center (BIC), US4, UAR 3420, F-33000 Bordeaux, France

6 University of Bordeaux, CNRS, Inserm, TBM-Core, US5, UAR3421, OncoProt, F-33000 Bordeaux, France

7 University of Bordeaux, Bordeaux Protéome, Bordeaux, France

8 Biomedical and Neuromotor Sciences, Alma Mater University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

9 Metabolism and Cell Signaling Laboratory, Spanish National Cancer Research Center (CNIO), Madrid, Spain

10 Service Analyses Métabolomiques, TBMCore, CNRS UAR 3427, Inserm US005, Université Bordeaux, F-33076, Bordeaux, France

11 University of Bordeaux, Animal Facility A2, Service Commun des Animaleries, F-33000 Bordeaux, France

12 Berlin Institute of Health (BIH), Berlin, Germany

$These authors contributed equally to this work