Researcher Contact

Benoît Chassaing

Chercheur Inserm à l’Institut Cochin

E-mail : rf.mresni@gniassahc.tioneb

Téléphone sur demande

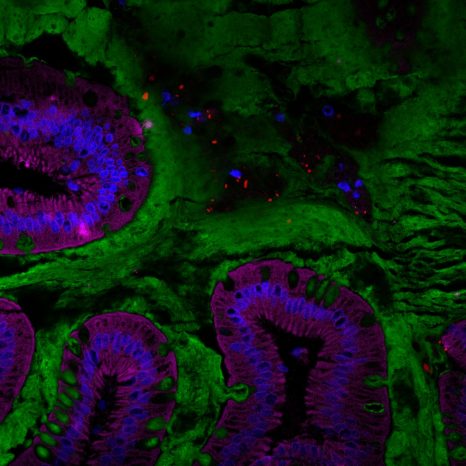

Visualization of the human gut microbiota (red) in the mucus layer (green) on the surface of the intestine. © Benoit Chassaing/Institut Cochin

Given the high prevalence of inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn’s disease, research is progressing to improve understanding of their risk factors and thus improve patient care. Scientists at Institut Cochin (Inserm/CNRS/Université de Paris), led by Inserm researcher Benoît Chassaing, had previously shown in mice that the presence of emulsifiers in many processed foods could promote intestinal inflammation. In a new study published in Gastroenterology, the same team has shown in healthy human volunteers that carboxymethylcellulose (CMC)[1], a widely used food emulsifier, affects the intestinal environment by altering the composition of the microbiota. The team stresses that more research is needed in order to characterize the long-term impact of this additive, including in individuals with inflammatory bowel disease.

Around 20 million people worldwide are thought to be affected by inflammatory bowel disease, which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Genetic factors have been identified to explain the intestinal inflammation that characterizes these conditions, but these predispositions are not enough to explain their onset. For several years now, many research teams have been looking at environmental factors.

One such team is that led by Inserm researcher Benoît Chassaing, at Institut Cochin (Inserm/CNRS/Université de Paris), which is interested in the impact of diet – and more specifically the role of certain food additives, such as emulsifiers (thickeners) – on the gut microbiota.

A particular focus of the team has been the impact of carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), a synthetic emulsifier added to many processed foods to improve texture and prolong shelf-life. Research in mice had previously found that CMC, as well as some other emulsifying agents, alters the composition of the gut microbiota, thereby worsening many chronic inflammatory diseases, such as colitis, metabolic syndrome, and colon cancer.

Therefore, in their latest study, the scientists sought to verify whether CMC could have the same impact in humans, given its growing use in processed foods since the 1960s despite having never been the subject of extensive clinical testing.

To conduct this clinical study, the scientists recruited a small group of healthy volunteers. The participants, housed at the study site for the duration of the research, were split into two groups. One consumed a diet that was strictly controlled and free of additives, and the other followed the same diet but enriched with CMC.

After two weeks, the researchers observed that, among the participants who had consumed CMC, the bacterial composition in the intestine was modified, with a marked decrease in the number of certain species known to play a beneficial role in human health, such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. In addition, the fecal samples of the participants receiving CMC were highly depleted of many beneficial metabolites. Finally, from the clinical viewpoint, these participants were more prone to abdominal pain and bloating.

Colonoscopies performed in these volunteers at the start and end of the study also showed that in a subset of the CMC group subjects, the intestinal bacteria were located closer to the walls of the intestine. This is a characteristic observed in inflammatory bowel diseases and type 2 diabetes.

“Our findings underline the need for further studies on this category of food additives, on larger numbers of people and for a longer duration. We also now want to know more about the differences in response to CMC between individuals. Why is it that only some develop inflammatory markers after consuming these additives? Are some people more sensitive to certain additives than others? These are the questions we want to answer and for which we are currently devising a variety of approaches,” specifies Chassaing.

The team is planning new clinical and preclinical studies that are expected to identify molecular markers of sensitivity to CMC in order to better explain these differences. Trials on larger groups of volunteers with inflammatory bowel disease are ongoing so as to identify the impact of the additive in these patients.

[1]CMC is also referred to as E466 on food product labeling.

Benoît Chassaing

Chercheur Inserm à l’Institut Cochin

E-mail : rf.mresni@gniassahc.tioneb

Téléphone sur demande

Randomized controlled-feeding study of dietary emulsifier carboxymethylcellulose reveals detrimental impacts on the gut microbiota and metabolome

Benoit Chassaing 1, #, Charlene Compher 2, Brittaney Bonhomme 3, Qing Liu 4, Yuan Tian 4,

William Walters 5, Lisa Nessel 6, Clara Delaroque 1, Fuhua Hao 4 Victoria Gershuni 7, Lillian

Chau 8, Josephine Ni 9, Meenakshi Bewtra 6,9, Lindsey Albenberg 10, Alexis Bretin 11, Liam

McKeever 3, Ruth E. Ley 5, Andrew D. Patterson 4, Gary D. Wu 9, Andrew T. Gewirtz 11, #, James D. Lewis 3

1 INSERM U1016, team ‘‘Mucosal microbiota in chronic inflammatory diseases’’, CNRS UMR 8104, Université de Paris, Paris, France

2 School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

3 Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

4 Center for Molecular Toxicology and Carcinogenesis, Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences, Pennsylvania State University, Pennsylvania, USA

5 Department of Microbiome Science, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tübingen, Germany

6 Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

7 Department of Surgery, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

8 Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of

Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

9 Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine,

University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

10 Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

11 Institute for Biomedical Sciences, Center for Inflammation, Immunity and Infection, Digestive Disease Research Group, Georgia State University, Atlanta

Gastroenterology, Novembre 2021