(c) BMJ / British Society of Gastroenterology 2016

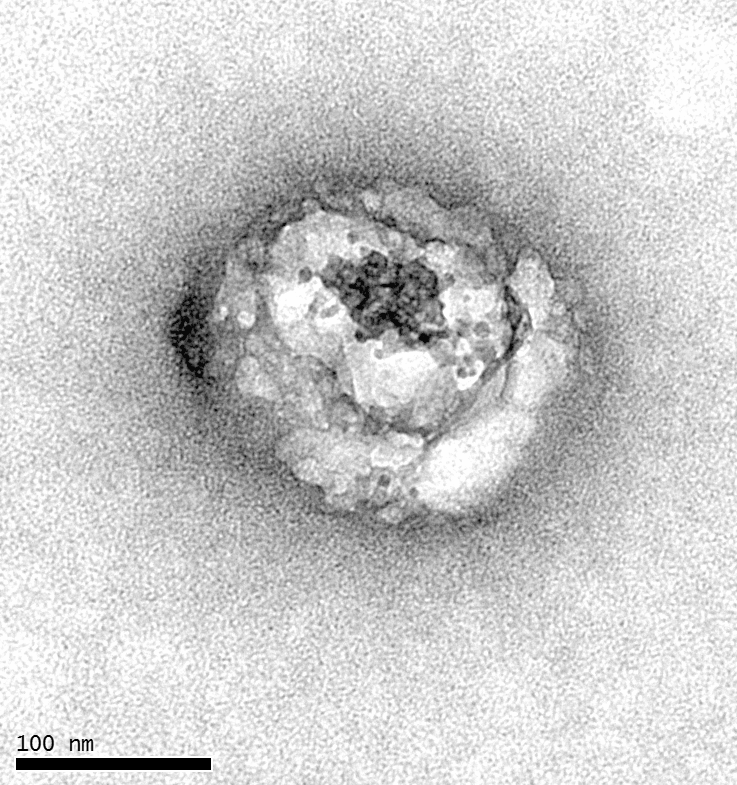

Scientists have finally observed the hepatitis C virus (or HCV) using an electron microscope. This is the first time since the virus became known in 1990. Inserm researchers at Tours (Inserm unit 966, “HIV and Hepatitis Viruses: Morphogenesis and Antigenicity”) have taken other scientists by surprise, including an American team believed to have accomplished this feat in 2013. The latter had in fact misunderstood the nature of the particles observed.

This research is published in the journal Gut.

The scientific community has waited twenty-five years for this. One of the greatest challenges of our era is to observe the hepatitis C virus, or HCV, under a microscope. It is responsible for 130 to 150 million cases of hepatitis C worldwide and about 700,000 deaths each year. This goal has become a reality thanks to the work by Inserm.

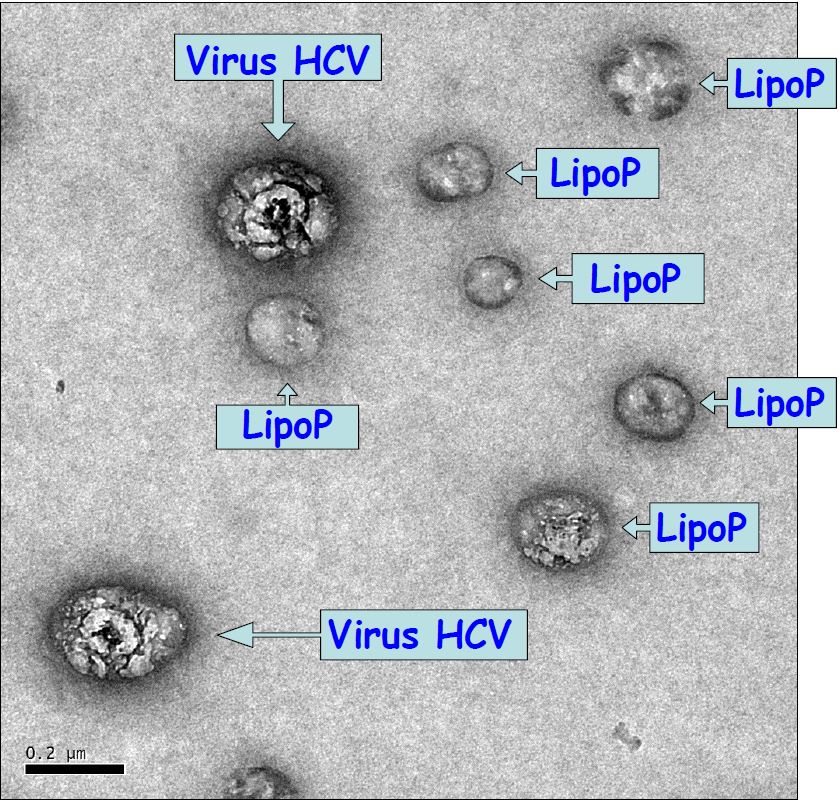

Viruses are normally discovered and described by observing them. However, HCV is an exception. All available data on this virus since 1990 were obtained by molecular biology as no one could view it under a microscope. This is due to the ability of the virus to hijack the machinery of the liver to give the appearance of a single lipid particle. This strategy allows the virus to easily penetrate cells and circumvent the immune system, also making it visually undetectable. “It resembles a single, small blank sphere amidst other blank lipospheres in the blood” explains Jean-Christophe Meunier, Inserm Research Fellow who is leading this study. “The virus takes advantage of the synthesis pathway for lipoproteins, particles that transport fat within an organism, so that it can replicate and closely associate with lipoprotein components.”

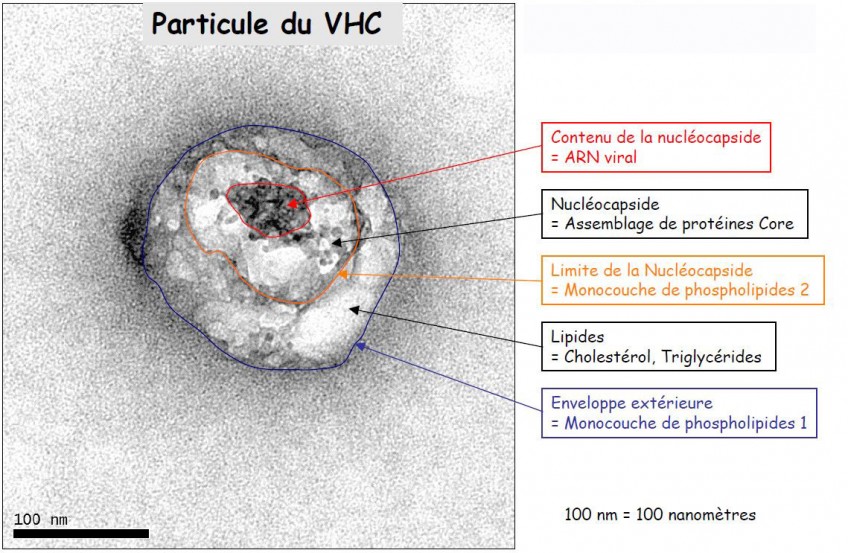

The virus effectively positions and attaches itself to the formation route of new lipoproteins and their components (phospholipids and their proteins).

Under its “disguise”, the virus becomes a genuine lipoviroparticle. This phenomenon was known for a long time, which makes it impossible to directly observe in the bloodstream of patients.

By contrast, lipoproteins sometimes inadvertently integrate viral proteins during formation, so it is possible to think that one is dealing with a virus when it is a single lipid particle. “This is precisely what happened in 2013 when an American team believed that they had observed the HCV virus”, explains Jean-Christophe Meunier.

Well-Structured Lipoviroparticles

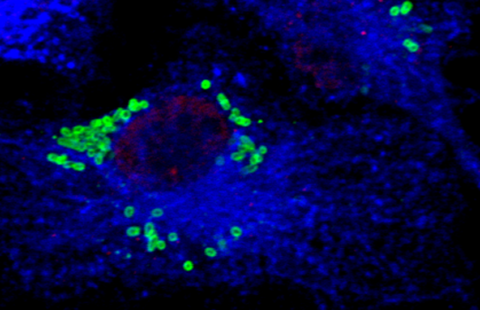

Except this time, researchers are sure of their findings. They have used several viral protein-specific antibodies and were finally able to distinguish these famous lipoviroparticles from single lipoproteins circulating in the serum of individuals.

This work was possible through the electron microscopy platform at the University of Toulouse backed by the Inserm unit.(c) BMJ / British Society of Gastroenterology 2016

And as scientists observed, these chimeric particles ultimately have a similar structure to [lipoproteins]. They take the form of a sandwich lipid composed of a viral RNA centre, core antigen and enveloped by a monolayer of phospholipids. This is surrounded by a mixture of fatty acids and cholesterol, which are further enveloped by a second monolayer of phospholipids. Finally, the size of the virus varies according to the number of lipid layers it contains. “This structure is completely consistent with previous molecular biology work that predicted this formation. These observations validate twenty-five years of work for the scientific community.” says Jean-Christophe Meunier.

(c) BMJ / British Society of Gastroenterology 2016

Apart from the satisfaction of accomplishing this technical feat, researchers stress the relevancy of this work. “Effective treatments are now available for hepatitis C, but a vaccine has yet to be found. Now, knowing the exact structure and organisation of these lipoviroparticles will be highly beneficial for those working in the field.”, states Jean-Christophe Meunier.