A significant breakthrough could revolutionize surgical practice and regenerative medicine. A team led by Ludwik Leibler from the Laboratoire Matière Molle et Chimie (CNRS/ESPCI Paris Tech) and Didier Letourneur from the Laboratoire Recherche Vasculaire Translationnelle (INSERM/Universités Paris Diderot and Paris 13), has just demonstrated that the principle of adhesion by aqueous solutions of nanoparticles can be used in vivo to repair soft-tissue organs and tissues. This easy-to-use gluing method has been tested on rats. When applied to skin, it closes deep wounds in a few seconds and provides a esthetic, high quality healing. It has also been shown to successfully repair organs that are difficult to suture, such as the liver. Finally, this solution has made it possible to attach a medical device to a beating heart, demonstrating the method’s potential for delivering drugs and strengthening tissues. This work has just been published on the website of the journal Angewandte Chemie.

In an issue of Nature published in December last year, a team led by Ludwik Leibler 1 presented a novel concept for gluing gels and biological tissues using nanoparticles 2. The principle is simple: nanoparticles contained in a solution spread out on surfaces to be glued bind to the gel’s (or tissue’s) molecular network. This phenomenon is called adsorption. At the same time the gel (or tissue) binds the particles together. Accordingly, myriad connections form between the two surfaces. This adhesion process, which involves no chemical reaction, only takes a few seconds. In their latest, newly published study, the researchers used experiments performed on rats to show that this method, applied in vivo , has the potential to revolutionize clinical practice.

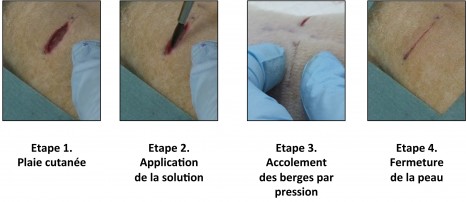

In a first experiment, the researchers compared two methods for skin closure in a deep wound: traditional sutures, and the application of the aqueous nanoparticle solution with a brush. The latter is easy to use and closes skin rapidly until it heals completely, without inflammation or necrosis. The resulting scar is almost invisible.

Phase 1 Skin injury

Phase 2 Application of the solution

Phase 3 Using pressure to hold the edges together

Phase 4 Skin closure

Illustration of the first experiment conducted by the resear chers on rats: a deep wound is repaired by applying the aqueous nanoparticle solution. The wound closes in thirty seconds.

© “Matière Molle et Chimie” Laboratory (CNRS/ESPCI Paris Tech)

In a second experiment, still on rats, the researchers applied this solution to soft-tissue organs such as the liver, lungs or spleen that are difficult to suture because they tear when the needle passes through them. At present, no glue is sufficiently strong as well as harmless for the organism. Confronted with a deep gash in the liver with severe bleeding, the researchers closed the wound by spreading the aqueous nanoparticle solution and pressing the two edges of the wound toget her. The bleeding stopped. To repair a sectioned liver lobe, the researchers also used nanoparticles: they glued a film coated with nanoparticles onto the wound, and stopped the bleeding. In both situations, organ function was unaffected and the animals survived.

“Gluing a film to stop leakage” is only one example of the possibilities opened up by adhesion brought by nanoparticles. In an entirely different field, the researchers have succeeded in using anoparticles to attach a biodegradable membrane used for cardiac cell therapy, and to achieve this despite the substantial mechanical constraints due to its beating. They thus showed that it would be possible to attach various medical devices to organs and tissues for therapeutic, repair or mechanical strengthening purposes.

This adhesion method is exceptional because of its potential spectrum of clinical applications. It is simple, easy to use and the nanoparticles employed (silica, iron oxides) can be metabolized by the organism. It can easily be integrated into ongoing research on healing and tissue regeneration and contribute to the development of regenerative medicine.

These contents could be interesting :

Anne Meddahi-Pellé, Aurélie Legrand, Alba Marcellan, Liliane Louedec, Didier Letourneur, Ludwik Leibler.

Angewandte Chemie. Parution en ligne le 16 avril 2014.

DOI: 10.1002/anie.201401043