When tumour cells acquire the capacity to move around and invade other tissues, there is a risk of metastases and cancer treatment becomes more difficult. Carine Rossé, INSERM research fellow and Philippe Chavrier, Research Director at CNRS, working alongside Dr. Anne Vincent-Salomon, medical researcher at the Institut Curie, have recently discovered one of the mechanisms that allow triple negative breast cancer cells to exit the mammary gland. These results were published on-line by PNAS on 21st April 2014.

Understanding how primary tumours infiltrate tissues and how certain cells detach and migrate to form metastases, is a major challenge in current cancer research. As such, the Institut Curie launched the incentive and cooperative research programme (PIC) “Breast Cancer: Invasion and Motility” in 2011 to give teams battling in this field access to important resources. Both programme coordinators Philippe Chavrier, Research Director at CNRS1 and medical researcher2 Anne Vincent-Salomon have joined forces in order to better understand how breast cancer cells move away and invade other tissues.

Furthermore, their latest discovery focuses on one of the most aggressive forms of cancer today – triple negative breast cancer. Dr. Anne Vincent-Salomon explains “this type of breast cancer is devoid of oestrogen and progesterone receptors with no overexpression of HER2. Women who have this type of cancer can neither benefit from hormonal therapy nor specific anti-HER2 therapy such as Herceptin”

A Tunnel in the Basement Membrane

Carine Rossé3 and Philippe Chavrier have discovered how these breast cancer cells break away from their original tissue. According to Philippe Chavrier “the tumour cells escape by digging a tunnel in the basement membrane that acts as a barrier around the mammary gland”.

His team has shown that the PKCλ protein and protease MT1-MMP are driving this cell “invasion”. If PKCλ is “depleted” in stem cells derived from aggressive breast cancer, the supply of MT1-MMP to the cell surface is inhibited and cell invasion is no longer possible.

Thanks to the Biological Research Centre4 at the Institut Curie, who keep close to 60,000 tumour samples, researchers have also directly studied these proteins in tumour samples. “We have seen expressive correlation between both proteins associated with unfavourable prognosis in breast cancer” explains a researcher. “We have also identified a mechanism that allows both proteins work together to promote breast tumour cell invasion.”

Researchers have found an essential step in the quest for the early identification of highly invasive tumours, or even blocking the formation of metastases.

“We have identified some interesting potential therapeutic targets, but they remain to be validated” clarified a biologist. Drugs capable of halting these mechanisms will follow in time with the help of chemists.

Chain Reaction

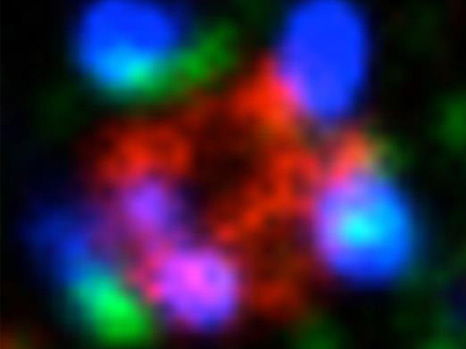

Zoom-in of the inside of a cell is used to see the reactions between various proteins triggered by PKCλ. This latest protease MT1-MMP traffic “control” (red) enables the association of cortactin (green) with dynamin 2 (blue). This reaction sequence is necessary to allow the cell separate from its neighbours and invade other tissues.

© Carine Rossé – Philippe Chavrier/ Institut Curie

1 1st class Research Director at CNRS, Philippe Chavrier is head of the “The Membrane and Cytoskeleton Dynamics” group “Subcellular Structure and Cellular Dynamics – Institut Curie/CNRS” laboratory, run by Bruno Goud.

2 Anne Vincent-Salomon is a medical pathologist in the Department of Biopathology at the Institut Curie Hospital Complex and has been a researcher in the “Genetics and Developmental Biology – Institut Curie/Inserm/CNRS” laboratory since January 2014, run by Prof. Edith Heard.

3 Carine Rossé is an INSERM research fellow within the “The Membrane and Cytoskeleton Dynamics” group, run by Philippe Chavrier.

4 Department of Biopathology at the Institut Curie Hospital Complex.

These contents could be interesting :

aResearch Center, Institut Curie, 75005 Paris, France; bMembrane and Cytoskeleton Dynamics, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Unité Mixte de Recherche 144, 75005 Paris, France; cSorbonne Universités, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, University of Paris VI, Institut de Formation Doctorale, 75252 Paris Cedex 5, France; dDepartment of Genetics, Institut Curie, 75005 Paris, France; eCell and Tissue Imaging Facility, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Unité Mixte de Recherche 144, 75005 Paris, France; fStructure and Membrane Compartments, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Unité Mixte de Recherche 144, 75005 Paris, France; gNikon Imaging Centre, Institut Curie, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 75005 Paris, France; hProtein Phosphorylation Laboratory, Cancer Research UK London Research Institute, London WC2A 3LY, United Kingdom; iDepartment of Molecular Cell Biology, Faculty of Medicine, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 3000 Leuven, Belgium; jDepartment of Tumor Biology, Institut Curie, 75005 Paris, France; kInstitut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale U830, 75005 Paris, France; and lDivision of Cancer Studies, King’s College London, Guy’s Campus, London WC2A 3LY, United Kingdom

PNAS 2014