The largest international study ever conducted on Alzheimer’s disease, as part of the IGAP (International Genomics of Alzheimer Project) international consortium, coordinated by the joint research unit comprising Inserm, the Pasteur Institute at Lille-University Lille Nord de France ‘Public health and molecular epidemiology of diseases associated with ageing’ and LabEx DISTALZ, directed by Philippe Amouyel, has identified eleven new regions of the genome involved in the appearance of this neuro-degenerative disease. This work provides an overview of the molecular mechanisms at the root of the disease, revealing a better understanding of the physiopathology of this curse. These results, described in an article published in the journal Nature Genetics dated 27 October 2013, were obtained through a unique global collaborative effort by the best researchers in the field.

Since 2009, 10 genes linked to Alzheimer’s disease have been discovered, providing a better understanding of this dreadful illness. However, a large part of individual susceptibility to develop this disease still remains unknown. Characterising this individual susceptibility carried by our genome required being able to compare patients’ DNA with that from healthy people, to find a few hundred variations among more than 3.5 billion genes making up our genome. Such an approach meant analysing the genomes of thousands of individuals, which cannot be done at a team scale or even that of a single country.

For this reason, in February 2010, managers from the four largest international research consortia on the genetics of Alzheimer’s disease decide to join forces to accelerate the discovery of new genes. In less than 3 years, under the IGAP programme, researchers have succeeded in identifying more genes than over the previous 20 years. They set up their study in two phases. The first consisted of reanalysing all their existing data based on common criteria, a total of more than 17,000 cases of Alzheimer’s disease collected in Europe and North America, comparing them to some 37,000 non-diseased controls. Using advances in human genome sequencing (1000 Genomes project), they were able to compare the distribution of more than 7 million mutations between these cases and controls, so as to select only 11,632 of them from this first phase.

In the second phase, researchers verified these results in independent samples from 11 different countries, totalling 8,572 patients and 11,312 controls. This confirmed the discovery of 11 new genes in addition to those already known and to locate 13 others still being confirmed.

These 11 new genes offer new opportunities for understanding the appearance of Alzheimer’s disease. One of the most significant associations has been found in the HLA-DRB5/DRB1 region of the major histocompatibility complex. This discovery is interesting for more than one reason. Firstly, it confirms the immune system’s involvement in the disease. In addition, this same regions is also found associated with two other neuro-degenerative diseases, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease. Another link could also be made with the SLC24A4 locus, which codes a protein involved in development of the iris and in the colour variation of hair and skin, and which is associated with the risk of high blood pressure.

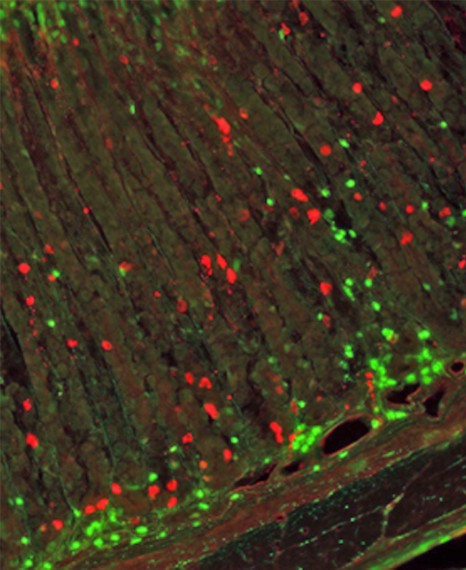

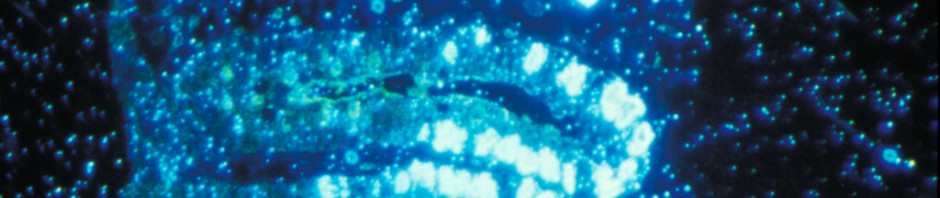

Some of these new genes confirm known hypotheses about Alzheimer’s disease, particularly the role of the amyloid pathway (SORL1, CASS4) and the Tau protein (CASS4, FERMT2). The role of the immune response and inflammation (HLA-DRB5/DRB1, INPP5D, MEF2C), already implicated by previous work from Inserm unit 744 (CR1[i], TREM2[ii]), is strengthened, as well as the role of cellular migration (PTK2B), lipid transport and endocytosis (SORL1). New hypotheses have also appeared, associated with hippocampal synaptic function (MEF2C, PTK2B), the cytoskeleton and axonal transport (CELF1, NME8, CASS4), as well as myeloid and microglial cell functions (INPP5D).

For the researchers, this discovery results in three main consequences. Firstly, this observation provides a better understanding of the physiopathology of Alzheimer’s disease, an essential step to discovering new treatments. Furthermore, this genome analysis better identifies the genetic profile of patients with a risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Finally, this work demonstrates that, faced with the complexity of such a disease, only the combined strength of global research will allow solutions to be found more quickly for this 21st century curse.

About Alzheimer Disease

These results, which demonstrate the many advances in understanding Alzheimer’s disease, involved teams from LabEx Distalz, and were able to be obtained through the support of the National foundation for Scientific Cooperation on Alzheimer’s disease and similar diseases, as well as the genotyping and analytical capabilities of the CEA National Genotyping Centre, the Study Centre for Human Polymorphism and the Pasteur Institute at Lille.

With the increasing life expectancy of human populations, the number of patients affected by Alzheimer’s disease is tending to rise in France and throughout the world. The leading cause of disorders of the memory and intellectual functions in the elderly, this illness is therefore a major challenge for public health.

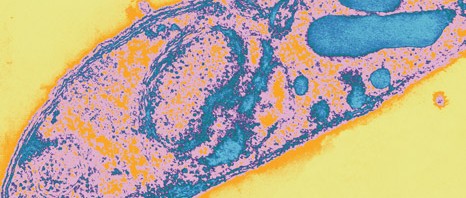

Alzheimer’s disease is one of the main causes of dependency in the elderly. It results in a deterioration of neurons in different regions of the brain. It is manifested by growing alteration in memory and cognitive functions, as well as by behavioural problems leading to progressive loss of independence. In France, Alzheimer’s disease affects more than 850,000 people and represents a major social and economic cost.

Alzheimer’s disease is characterised by development of two types of brain lesions: amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary degeneration. Amyloid plaques arise from extracellular accumulation of a peptide, the amyloid β peptide (Aβ), in specific areas of the brain. Neurofibrillary degeneration is intra-neural lesions arising from abnormal aggregation, in the form of filaments, of a protein called the Tau protein.

Identifying genes that contribute to the appearance of Alzheimer’s disease and its development will lead more rapidly to tackling the physiopathological mechanisms underlying this disease, to identifying target proteins and metabolic pathways for new treatments, and to offering methods to identify subjects at greatest risk when effective preventive treatments are available.

The International Genomics of Alzheimer Project, IGAP

In February 2011, researchers from the four leading research consortia into the genetics of Alzheimer’s disease were brought together to speed up the discovery and mapping of genes involved in Alzheimer’s disease. Their research work was conducted in European and North American universities. They combined the knowledge, staff and resources of the European Alzheimer’s Disease Initiative (EADI) in France, directed by Philippe Amouyel, doctor and researcher, Director of the joint research unit comprising Inserm, the Pasteur Institute at Lille-University Lille 2 ‘Public health and molecular epidemiology of diseases associated with ageing’ and LabEx DISTALZ. The Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Consortium (ADGC) in the United States, directed by Gerard Schellenberg, researcher at the Pennsylvania University Faculty of Medicine. The Genetic and Environmental Risk in Alzheimer’s Disease (GERAD) in the United Kingdom, directed by Julie Williams, researcher at Cardiff University. Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE), directed by Sudha Seshadri, doctor at Boston University.

[i] Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Lambert JC et al. Nature Genetics 2009. 41: 1094-1099.

[ii] TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease.

Guerreiro R, et al. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368(2): 117-27.