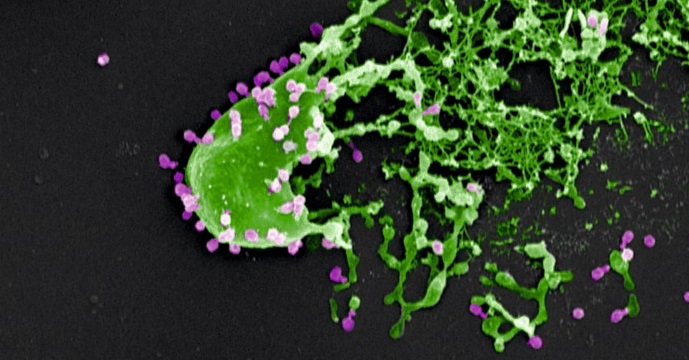

Bacteria (in green) assaulted and killed by bacteriophages (in purple). Electron microscopy image provided courtesy of M. Rohde and C. Rohde (Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research, Braunschweig/Leibniz Institute DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany) and colorized by Dwayne Roach (Institut Pasteur).

© M. Rohde and C. Rohde

Phage therapy involves the use of bacteriophages, or phages, for treating bacterial infections. Phages are viruses that specifically attack bacteria and are harmless to humans. A significant decline in the use of this therapeutic strategy introduced 100 years ago was seen in the West following the development of antibiotics. However, there is now new interest in phage therapy, especially in Europe, given the alarming increase in the number of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections.

Until now, there has been insufficient scientific data to understand how phage therapy works in vivo. While most in vitro studies have proven that phages specifically target and kill bacteria, none of these studies took account of the importance of the host’s response to this activity.

Two Institut Pasteur teams (Laurent Debarbieux’s Bacteriophage-Bacteria Interactions in Animals Group and the Innate Immunity Unit led by James di Santo (Inserm U1223)) in partnership with Joshua Weitz’s team at the Georgia Institute of Technology (Atlanta, U.S.), recently showed the importance of patients’ immune status in terms of the chances of phage therapy success. This finding is the result of an original dual approach combining an animal model and mathematical modeling.

In order to evaluate the efficacy of treatment with a single phage species, the researchers focused on the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which is involved in respiratory infections such as pneumonia. This bacterium, which is resistant to carbapenems, or ‘antibiotics of last resort’, was ranked by WHO as one of the four biggest global threats in terms of antibiotic resistance.

The researchers demonstrated that phage therapy is effective in animals with a healthy immune system (known as ‘immunocompetent’). The innate immune system can be triggered quickly and phages initially act in tandem with it to fight off infection. Then, after 24 to 48 hours, some bacteria naturally develop resistance to the phages which consequently cease to function. The innate immune system then takes over to destroy the bacteria. Of all the immune cells involved, neutrophils (white blood cells originating in the bone marrow) play a predominant role.

In parallel, in silico simulations have shown that the innate response needs to destroy 20-50% of the bacteria in order for phage therapy to be effective, regardless of whether phage resistance is observed. Thus, in the model studied, the researchers proved that there are no circumstances under which phages are capable of eradicating a P. aeruginosa infection alone.

These findings are particularly significant since they suggest that patients’ immune status should be considered when undertaking phage therapy. Laurent Debarbieux explains: “In terms of clinical consequences, one could reconsider the selection of patients likely to benefit from phage therapy. It may not be appropriate or recommended for people with severe immunodeficiency”.

The researchers are now planning to decipher the exact immune processes involved and the underlying mechanisms. At the same time, clinical trials are ongoing, notably including the Phagoburn trial on skin infections in burn patients funded by the European Union’s 7th Framework Programme.