Our bodies have ten times the amount of microbes than human cells. This set of bacteria is called microbiota. In some instances, bacteria known as pathogens can cause infectious diseases. However, these micro-organisms can also protect us from certain diseases. Researchers from Inserm, Paris Descartes University and the CNRS (French National Centre for Scientific Research), through collaboration with teams from China and Sweden, have recently shown how microbiota protects against the development of type 1 diabetes. This research is published in the Immunity journal, 4 August 2015.

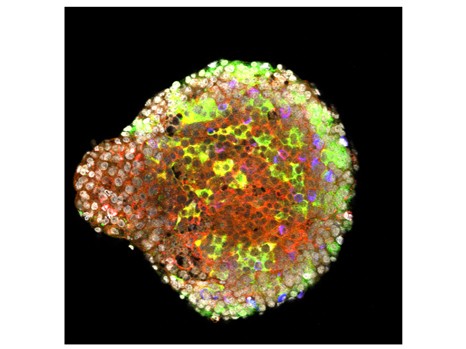

A pancreatic islet of Langerhans expressing the immunoregulator antimicrobial peptide CRAM (in red). The insulin-producting beta-cells are in green and the glucagon-producting alpha-cells are in blue. © Julien Diana

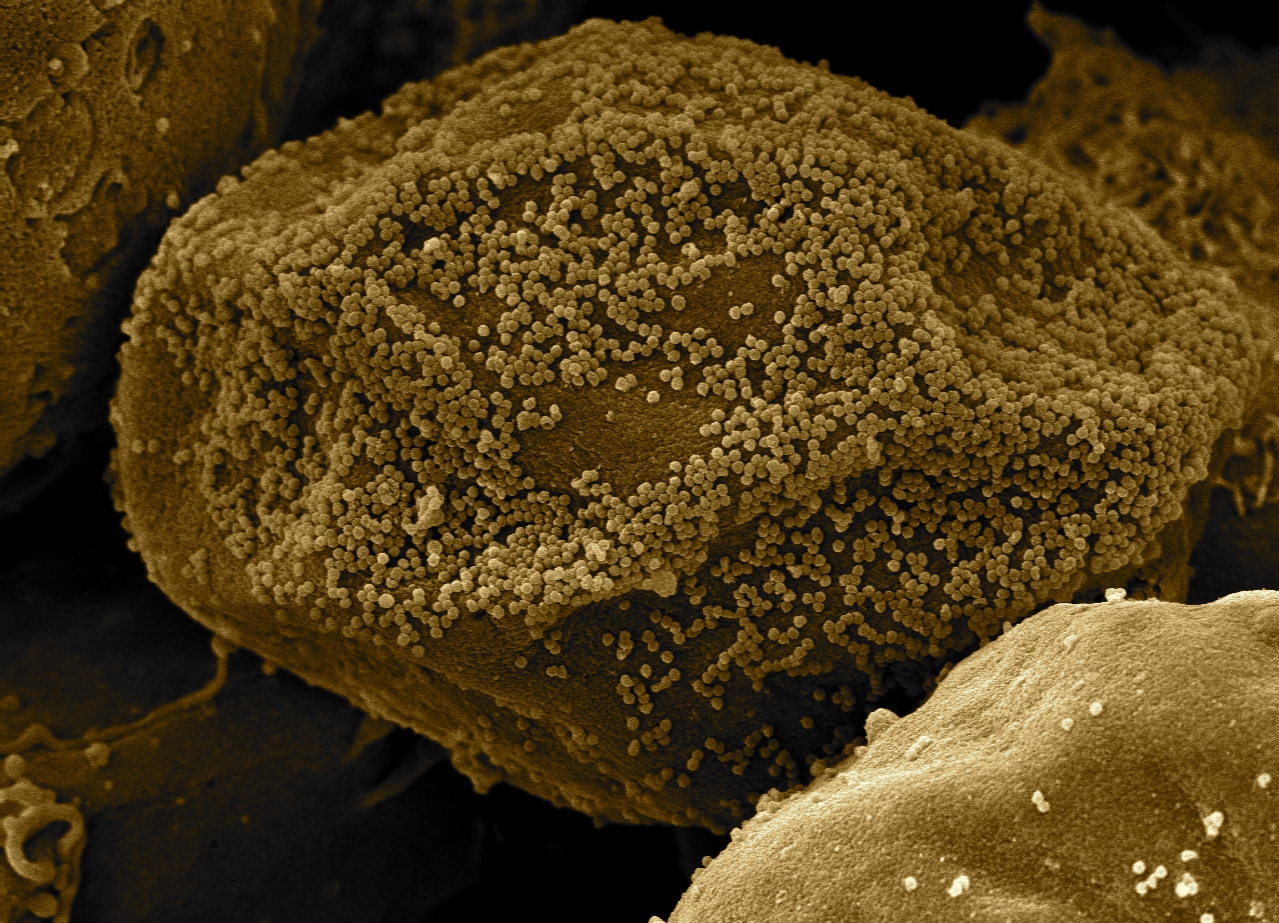

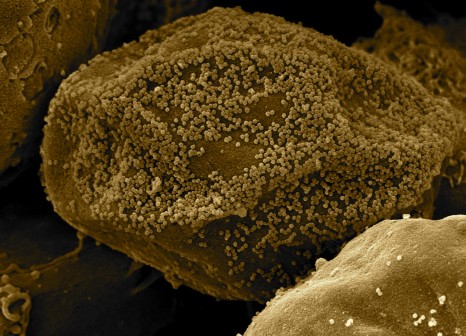

To combat pathogens, the immune system has developed various mechanisms to detect, defend against and even destroy micro-organisms that are harmful to the body. This includes antimicrobial peptides and natural proteins that destroy pathogenic bacteria by disrupting their cellular membrane. Not only are they produced by immune cells, they are also produced by cells whose functions are not immune-related.

A research team coordinated by Julien Diana, an Inserm Research Fellow at Inserm Unit 1151 “Institut Necker-Enfant Malades” [Necker Institute for Sick Children] (Inserm/CNRS/Université Paris Descartes), is focussing on a category of antimicrobial peptides, i.e. cathelicidins. Apart from their protective function, these peptides have also exhibited immunoregulatory abilities against several autoimmune diseases. As such, scientists hypothesise that cathelicidins may be involved in the control of type 1 diabetes, an autoimmune disease where certain cells in the immune system attack beta cells in the pancreas which secrete insulin.

Firstly, they observed that beta pancreatic cells in non-diseased mice produce cathelicidins and that, interestingly, this production is impaired in diabetic mice.

To test this hypothesis, they are injecting diabetic mice with cathelicidins where production is defective.

“Injecting cathelicidins inhibits the development of pancreatic inflammation and, as such, suppresses the development of autoimmune disease in these mice” states Julien Diana.

Given that the production of cathelicidins is controlled by short-chain fatty acids produced by gut bacteria, Julien Diana’s team are studying the possibility that this may by the cause of the cathelicidin deficiency associated with diabetes. Indeed, researchers have observed that diabetic mice have a lower level of short-chain fatty acids than that found in healthy mice.

By transferring part of the gut bacteria from healthy mice to diabetic mice, they are re-establishing a normal level of cathelicidin. Meanwhile, the transfer of micro-organisms reduces the occurrence of diabetes.

For the authors, “this research is further evidence of the undeniable role microbiota plays in autoimmune diseases, particularly in controlling the development of autoimmune diabetes”. Preliminary data, as well as scientific literature, suggest that a similar mechanism may exist in humans, paving the way for new therapies against autoimmune diabetes.

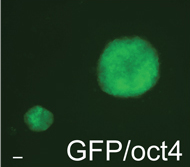

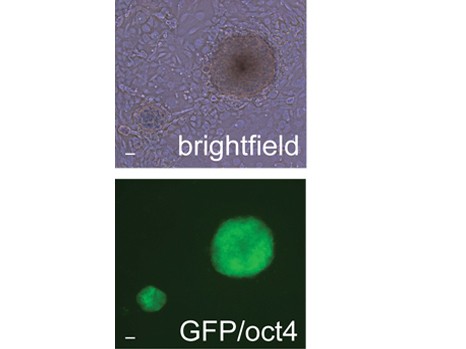

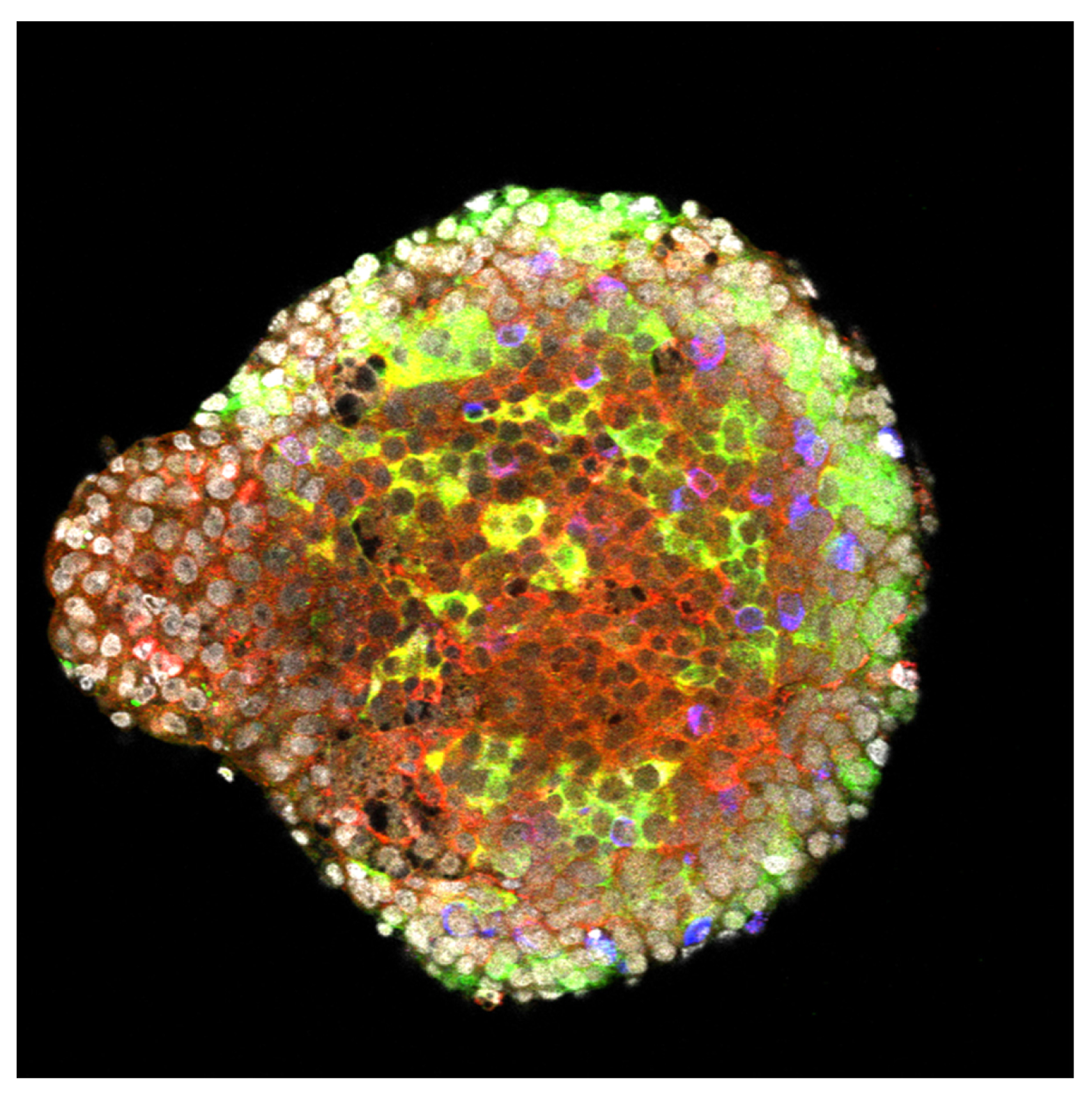

Human embryonic stem cells have the potential to form in vitro neural tube -like structures of the embryo. ©Inserm/Benchoua Alexandra

Human embryonic stem cells have the potential to form in vitro neural tube -like structures of the embryo. ©Inserm/Benchoua Alexandra