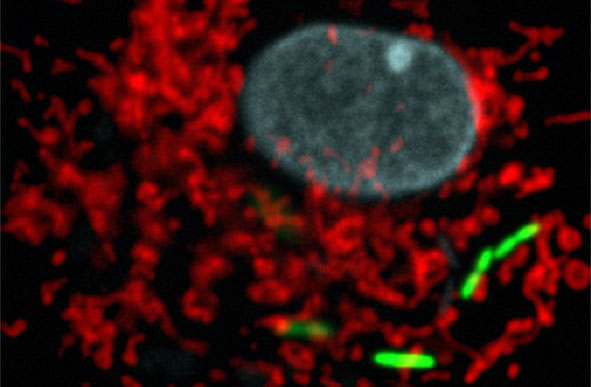

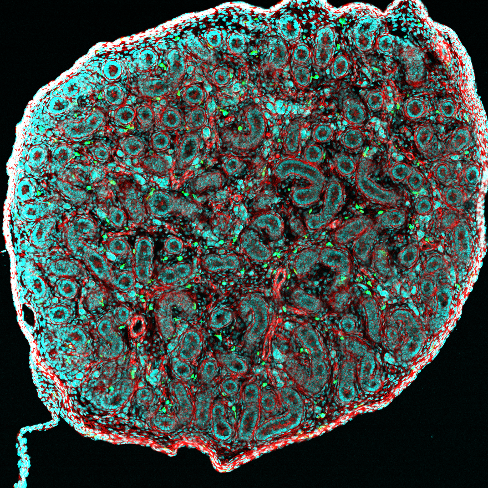

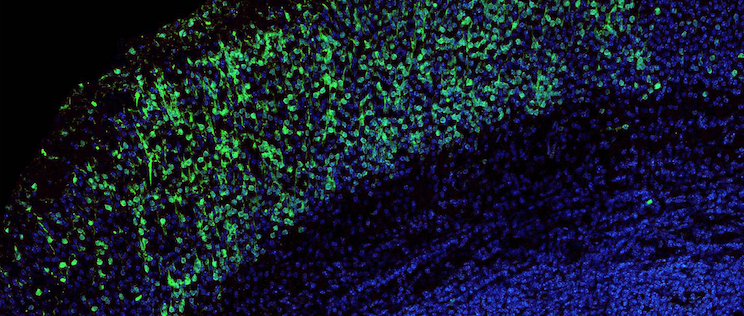

Legionella pneumophila (green), the bacterium responsible for severe acute lung disease inside eukaryotic cells. Mitochondrial network in red, nucleus in blue. © Institut Pasteur.

Scientists at the Institut Pasteur, CNRS and Inserm, together with a team from Switzerland*, have shown that the bacterial pathogen Legionella pneumophila (the causative agent of Legionnaires’ disease or legionellosis) has developed a specific strategy to target the host cell mitochondria, the organelles in charge of cellular bioenergetics. By changing the shape of these host organelles, L. pneumophila impairs mitochondrial respiration leading to metabolic changes in the host cell that are instrumental for the pathogens replication in human cells. This work provides precious information on how a pathogen manipulates the cellular metabolism to replicate intracellularly, and proposes a new concept of protection of host cells from Legionella-induced mitochondrial changes in order to fight infection. This research is published online on August 31, at the Cell Host & Microbe website.

Intracellular pathogens adopt various strategies to circumvent the defences of the host cell and to proliferate intracellularly. One specific strategy is to target host organelles like the mitochondria. Mitochondria are well-defined cytoplasmic organelles, which take part in a variety of cellular metabolic functions. Mitochondria are important as they supply the energy to the cell, thus they are also referred to as the ‘power house’ of the cell. Some bacteria, including Legionella pneumophila, are able to alter mitochondrial functions to the pathogens advantage.

L. pneumophila is a bacterial pathogen that causes Legionellosis – a disease characterized by an acute pulmonary infection, which is often fatal when not treated promptly. In France, between 1200 and 1500 cases are identified each year, with mortality rates ranging from 5 to 15%.

Researchers from the Institut Pasteur, CNRS and Inserm, in collaboration with a team from Switzerland, have discovered a previously unknown mechanism by which L. pneumophila targets mitochondria to modulate mitochondrial dynamics and thereby impairs mitochondrial respiration which in turn leads to a change in the cellular metabolism. These metabolic changes in the host cell favour bacterial replication. Thus the rewiring of cellular bioenergetics to create a replication permissive niche in host cells is a core virulence strategy of L. pneumophila.

The researchers have identified the following mechanism: L. pneumophila establishes transient, highly dynamic contacts with host mitochondria and secretes an enzyme called MitF that modifies the shape of the mitochondria by inducing DNM1L (a host protein that is necessary for fragmenting mitochondria) depended mitochondrial fragmentation. Surprisingly, L. pneumophila induced mitochondrial fragmentation is independent of cell death and ultimately impairs mitochondrial respiration, whereas cellular glycolysis is increased. Thus the bacterial-induced changes in mitochondrial dynamics promote a Warburg-like phenotype (which is characteristic of cancerous cells) in the infected cell that favours bacterial replication.

Researchers also brought the proof of concept that protecting host cells from Legionella-induced mitochondrial changes may help to fight infection. Indeed, pre-treating of human cells with a compound that inhibits changes in mitochondrial morphology allows protecting the host cell from Legionella-induced changes of mitochondria and restricts bacterial infection of human cells.

As Carmen Buchrieser, head of the Biology of the intracellular bacteria research unit at the Institut Pasteur and researcher at CNRS, explains: “this is an important discovery as our results showcase a key strategy used by L. pneumophilia for intracellular replication. By targeting mitochondria, the bacterium ensures that the host cell will be permissive to its replication. It is therefore essential that researchers also focus their studies on metabolic changes caused by pathogenic bacteria, in order to develop new therapeutic strategies against legionellosis and other diseases linked to intracellular bacteria.”

This work sheds new light on how a pathogen shapes host metabolic responses during infection of human cells and shows that metabolic changes in the host cell are instrumental for the pathogens replication in human cells and thus to cause disease. It also proposes a new concept, which is to treat infections by inhibiting pathogen induced metabolic changes.

* The researchers and scientific teams involved are: Carmen Buchrieser, head of the Biology of the intracellular bacteria unit at the Institut Pasteur and associated to CNRS, Hubert Hilbi, of the University of Zürich Switzerland, Priscille Brodin, at the Institut Pasteur Lille and associated to CNRS and INSERM, and Jean-Christophe Olivo-Marin, head of the Bioimage analyses unit at the Institut Pasteur.