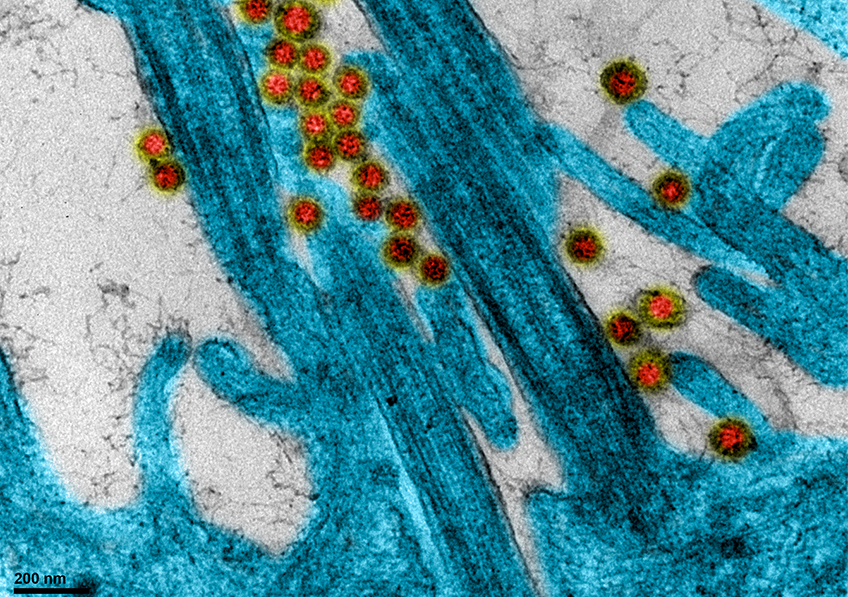

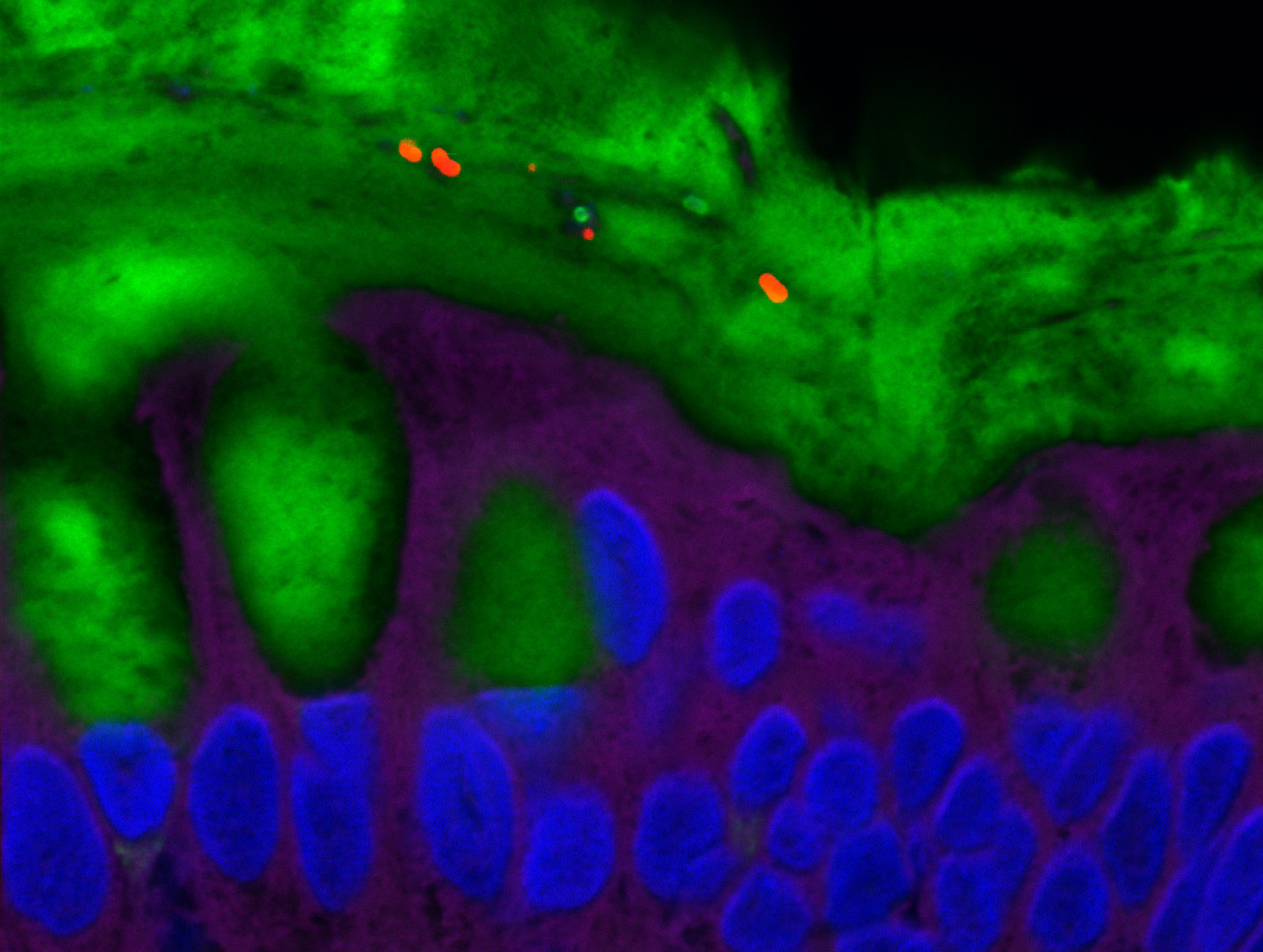

SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus attached to the cilia of human respiratory epithelial cells.© Manuel Rosa-Calatrava, INSERM ; Olivier Terrier, CNRS ; Andrés Pizzorno, Signia Therapeutics ; Elisabeth Errazuriz-Cerda UCBL1 CIQLE. VirPath (Centre International de Recherche en Infectiologie U1111 Inserm – UMR 5308 CNRS – ENS Lyon – UCBL1). Colorized par Noa Rosa C.

A study by Inserm and Dijon University Hospital based on French nationwide data on around 130,000 patients hospitalized for either COVID-19 or seasonal influenza shows that the mortality rate among those admitted for COVID is three times higher than that of seasonal influenza. These findings have been published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine

This study uses data from the French national administrative database (medicalized information system program – PMSI), which contains information on all patients admitted to public and private hospitals in France, such as the reasons for their admission and the treatment they received. The researchers compared the admissions for COVID-19 (between March 1 and April 30, 2020) with those for seasonal influenza (between December 1, 2018 and February 28, 2019).

The results reveal:

- A mortality rate among the patients hospitalized for COVID-19 three times higher than that of those admitted for seasonal influenza. Of the 89,530 patients admitted for COVID, 15,104 [16.9%] died versus 2,640 [5.8%] of the 45,819 patients hospitalized for influenza.

- More COVID-19 patients required admission to intensive care with an average stay that was almost twice as long (15 days versus 8 days).

- Fewer children under 18 years of age were hospitalized for COVID-19 than for seasonal influenza, but a larger proportion of the patients younger than 5 years needed intensive care support for COVID (14 out of 613) than for influenza (65 out of 6973). The mortality rate for the children under 5 years of age was similar for both groups and very low (less than 0.5%).

- Almost twice as many people were hospitalized for COVID-19 at the peak of the pandemic compared to those who had been hospitalized for influenza at the peak of its 2018/2019 season.

- In addition, a larger proportion of the COVID-19 patients had a severe form of the illness requiring intensive care than those with influenza. Looking at the number of admissions to intensive care: out of the 89,530 COVID-19 patients, 14,585 [16.3%] were admitted to intensive care versus 4,926 [10.8%] of the 45,819 influenza patients.

- More than one in four COVID-19 patients suffered from acute respiratory failure, versus fewer than one in five with influenza.

- Consistent with previous reports, the most common underlying medical conditions among the patients admitted with COVID-19 were hypertension (33.1%), overweight or obesity (11.3%), and diabetes (19.0%).

The researchers point out that their study has several limitations. In particular, testing practices for influenza are likely to be highly variable across hospitals, whereas practices for COVID-19 may be more standardized. This may partly explain the increased number of admissions for COVID-19 compared to seasonal influenza. In addition, the difference in hospitalization rates may be partly due to existing immunity to influenza in the population, either from previous infection or vaccination.

Nevertheless, the conclusions of this research confirm the importance of measures to prevent the spread of both diseases. Measures that are particularly relevant at a time when several countries are preparing for the COVID-19 pandemic to continue in parallel with seasonal influenza outbreaks during the winter months.

“This study is the largest to date comparing the two diseases and confirms that COVID-19 is much more serious than influenza. The finding that the COVID-19 death rate was three times higher than that of seasonal influenza is particularly striking when one recalls that in the last five years the 2018/2019 influenza season has been the worst in France in terms of number of deaths,” declares Catherine Quantin, researcher at Inserm and Professor at Dijon University Hospital.

“Taken together, these findings clearly indicate that COVID-19 is much more severe than seasonal flu. While no treatment has yet been shown to be effective in preventing serious illness in COVID-19 patients, this study underlines the importance of the various prevention measures (barrier measures) and highlights the need for access to effective vaccines,” concludes Pascale Tubert-Bitter, research director at Inserm.