© Julie Borgese

© Julie Borgese

Inserm has published a new Collective Expert Review on the theme of multiple disabilities, commissioned by the French National Solidarity Fund for Autonomy (CNSA). During the 3 years it took to prepare it, a group of 12 experts reviewed over 3400 documents from the international scientific literature available as at the second half of 2023. The conclusions and recommendations of this Collective Expert Review provide useful new elements to improve care and help answer questions regarding the consideration, interactions and integration of people with multiple disabilities.

The term ‘multiple disabilities’ refers to the permanent consequences of a lesion (genetic or accidental) that occurs during the brain’s development and results in severe motor impairment and intellectual disability evaluated as severe to profound. Multiple disabilities are associated not just with extremely restricted communication, autonomy and mobility, but also with comorbidities, sensory impairment and behavioural disorders.

In France, the prevalence of multiple disabilities is currently estimated at around 0.3-0.5 people in every 1000.

Complex clinical care

The situations caused by multiple disabilities differ greatly from one person to another, with many disorders that are interlinked. Each must be taken into account when setting up care.

For example, epilepsy, which is very common, presents as a veritable secondary disability. As for respiratory disorders, they constitute the leading cause of mortality and emergency hospitalisation among people with multiple disabilities.

Other disorders that are commonly encountered include:

- difficulty feeding oneself, digestive and nutritional disorders;

- due to very limited mobility, bone fragility in children and osteoporosis in adults, excessively weak muscle tone, posture defects and orthopaedic deformities (scoliosis, hip dislocation, etc.);

- frequent sleep disorders in children (significantly impacting the quality of life of those around them);

- disruptions to puberty (late or early).

Pain, often multifactorial, is common, sometimes chronic from an early age, and rarely expressed through the usual modes of communication (such as verbal complaints). This makes it difficult to evaluate, leading to the risk of underestimating it. Generally dependent on a third party (healthcare professional or caregiver), such evaluation therefore raises ethical and methodological questions.

The expert group recommends:

- for motor disorders: rehabilitation via adapted interventions aimed at promoting voluntary movements and motor learning; on a daily basis, prevention of the consequences of impaired motor activity by reducing passive activities (watching television for example) in favour of movement-based activities;

- for intellectual disability: promotion of interaction-generating environments for people with multiple disabilities and their integration into everyday social spaces, with the appropriate conditions and trained personnel. An appropriate and soothing environment makes it possible to improve the common behavioural disorders (self-aggression, repetitive behaviours, etc.) that are largely linked to living environment;

- for pain: systematically screen for its presence, evaluate its intensity, frequency and duration using specific validated tools and search for its cause(s) using a detailed examination;

more globally: generalise validated methods for evaluating quality of life, combining different objective approaches in a complementary manner (evaluations by medical staff, parents and other people close to the patient) and self-evaluation.

A French cohort of children and adults with multiple disabilities (Eval-PLH) is ongoing. Future data will make it possible to evaluate, for example, the mortality rate and causes of death of people with multiple disabilities.

Support and social integration of people with multiple disabilities

Alongside medical care, multiple disabilities involve lifelong comprehensive and individualised support, in order to offer people a life plan that is appropriate to their various needs and their personal development pathway. Evaluation of the skills, difficulties (medical, psychological, interpersonal) and methods of communication of people with multiple disabilities must be carried out regularly.

This support is crucial in terms of educational and social aspects, particularly for the core subject of being able to communicate, but also for learning, schooling, inclusion and social participation. People with multiple disabilities have the possibility to learn throughout their lives if the right arrangements are made. Some skills, if stimulated in early childhood, improve socialisation and communication over the long term. In addition, people with multiple disabilities can participate in various activities of daily and social life thanks to certain aids, methods and tools that make their environment more suitable.

The expert group recommends:

- using the severity rating scale for multiple disabilities, validated in French to evaluate individual skills and difficulties;

- enabling children with multiple disabilities to have access to education tailored to their needs and enabling them to develop their capacities to the fullest;

- reflecting on the types of learning that benefit children with multiple disabilities in order to build a ‘tailored’ educational pathway within teaching units involving teams from both specialised institutions and ordinary schools;

- implementing a combination of several modes of communication (voice, touch, gaze, gestures, etc.) and Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) individually adapted to the person’s motor and cognitive abilities and enabling both communication and mutual understanding – this may be a succession of gestures (for example, inspired by sign language) or objects with a precise meaning, but also technological means.

The central roles of those close to people with multiple disabilities

Because of their dependence and extreme physical and psychological vulnerability, people with multiple disabilities need a high level of care and attention. The family, other people close to them and professionals are therefore highly impacted on the practical (care, day-to-day organisation) and emotional levels and play a prominent role in support. The evaluation of needs, their coordinated implementation and their adaptation to advancing age demand a multidisciplinary approach and complex coordination between carers.

While the French system (care for people with multiple disabilities, approval of reference and competence centres for multiple disabilities of rare causes) is likely to meet the various life-long needs of the people concerned, the coordination and continuity of the care pathway is not always optimal.

Thus the transition to adulthood, a continuous process that starts between 13 and 15 years of age, remains difficult with medical, social and legal implications for the individual and their family. The severity of multiple disabilities grows with age, consequently increasing the level of dependence. The end of life of people with multiple disabilities also raises many challenges relating to ethics and resources.

Intimacy and affectivity are essential for someone who is in a situation of total physical dependence and without a unified perception of their body. Affection and attention therefore play a decisive role in care and learning.

When it applies to someone whose mental life and psychological and emotional development develop in an atypical way, the question of sexuality finds itself confronted against communication problems and ethical questions.

Finally, in a context where the person is entirely dependent on the interpretations of their communication partners, the high level of vulnerability – physical, psychological and communicational – which characterises multiple disabilities reinforces the risks of abuse (voluntary or involuntary), which can accumulate.

The expert group recommends:

- conducting early identification and diagnosis of multiple disabilities in children, involving families from the outset and providing adequate support;

- offering early interventions while promoting care in inclusive early childhood environments in partnership with specialised services;

- to prevent institutional abuse, the establishment of practice analysis groups, solid ongoing training, a culture of well-treatment and a monitoring unit in institutions and departments. However, the experts warn that these measures cannot replace sufficient human resources with the appropriate equipment;

- to prevent parental abuse, take into account the psychological suffering of parents and encourage pair work and group- and multidisciplinary exchanges. Patient organisations and social media discussion groups are ways of limiting the effects of social exclusion, especially for parents forced to give up work;

- to guard against forms of involuntary or passive abuse (laissez-faire, negligence, lack of knowledge, etc.) that may be linked to inappropriate care, interpersonal habits likely to intensify communicational vulnerability, or even an underestimation of the person’s cognitive abilities that may lead to a negation of their psychological life;

- to recognise and take into account the person’s manifestations of sexuality, to question what the modes of this sexuality may be; to not neglect emotional life by clearly distinguishing it from the questions of sexuality.

The Inserm Collective Expert Reviews

Developed by Inserm since 1993, the Collective Expert Reviews constitute an approach to evaluating and summarising scientific knowledge on public health themes.

These Collective Expert Reviews respond to the requests from institutions wishing to have recent research data at their disposal. Their objective is to share knowledge and provide independent scientific insights into specific health questions, to aid public decision-making in the field of population health.

The scientific framework, bibliographic support, coordination and promotion of the Collective Expert Reviews are ensured by the Inserm Collective Expert Review Unit.

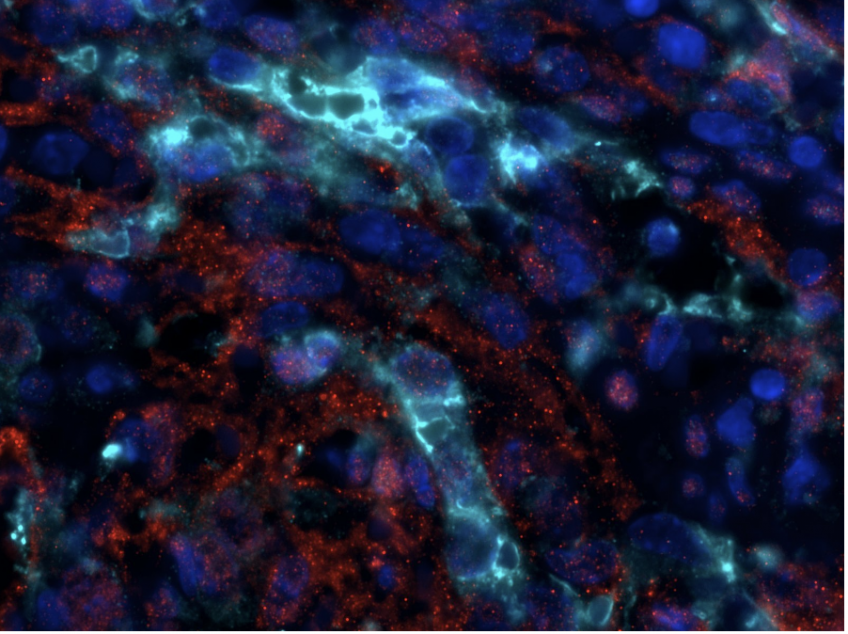

Phospho-ERK (red), Green Fluorescent Protein (cyan) and DAPI coimmunofluorescence on spleen sections from mice carrying a KRAS G12C endothelial mutation © Guillaume Canaud

Phospho-ERK (red), Green Fluorescent Protein (cyan) and DAPI coimmunofluorescence on spleen sections from mice carrying a KRAS G12C endothelial mutation © Guillaume Canaud