© Inserm

© Inserm

‘Through its Prizes, Inserm celebrates this year five emblematic winners of our collective effort to conduct and support health research with efficacy and creativity,’ emphasises Inserm CEO, Prof. Didier Samuel. Throughout 2023, and as Inserm prepares to celebrate its 60th anniversary next year, its staff has continued to promote the health of all citizens thanks to major advances across all areas of biomedical research. The work of the five scientists selected to receive this year’s prizes reflects the rich and innovative nature of Inserm research. The Inserm Grand Prize is awarded to Nadine Cerf-Bensussan, a pioneer in the exploration of the microbiota, who has been studying intestinal immunity for more than forty years in order to improve patient care.

Nadine Cerf-Bensussan, Inserm Grand Prize

© François Guénet/Inserm

© François Guénet/Inserm

Inserm Research Director Nadine Cerf-Bensussan heads up the Intestinal Immunity laboratory at the Imagine Institute in Paris, where she is studying the role of the intestinal immune system, which on the one hand protects us from pathogens, but on the other has to tolerate the nutrients and many bacteria present in the microbiota.

More specifically, her work aims to better understand intestinal pathologies, including gluten-induced coeliac disease, as well as the links between the gut microbiota and its host.

Although this type of research is gaining traction right now – with the general public being familiar with the terms ‘microbiota’ and ‘gluten intolerance’ – this was not the case when she began her career 40 years ago.

She entered the field somewhat by chance, first through a hospital internship in Claude Griscelli’s Department of Immunology and Haematology at Necker-Enfants Malades, then by moving towards a post-graduate diploma (DEA) and an internship at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston where she developed her first antibody against intestinal lymphocytes in rats.

Back in France in the early 1980s, she committed herself to research, successfully completing a competitive examination to become an Inserm staff scientist in 1987 – still in the team of Claude Griscelli, who went on to serve as Inserm CEO from 1996 to 2001. There Cerf-Bensussan developed the first antibody against human intra-epithelial lymphocytes and saw in coeliac disease – which is now widely discussed in the media – an ideal model for studying the role of these lymphocytes and, more broadly, intestinal immunity.

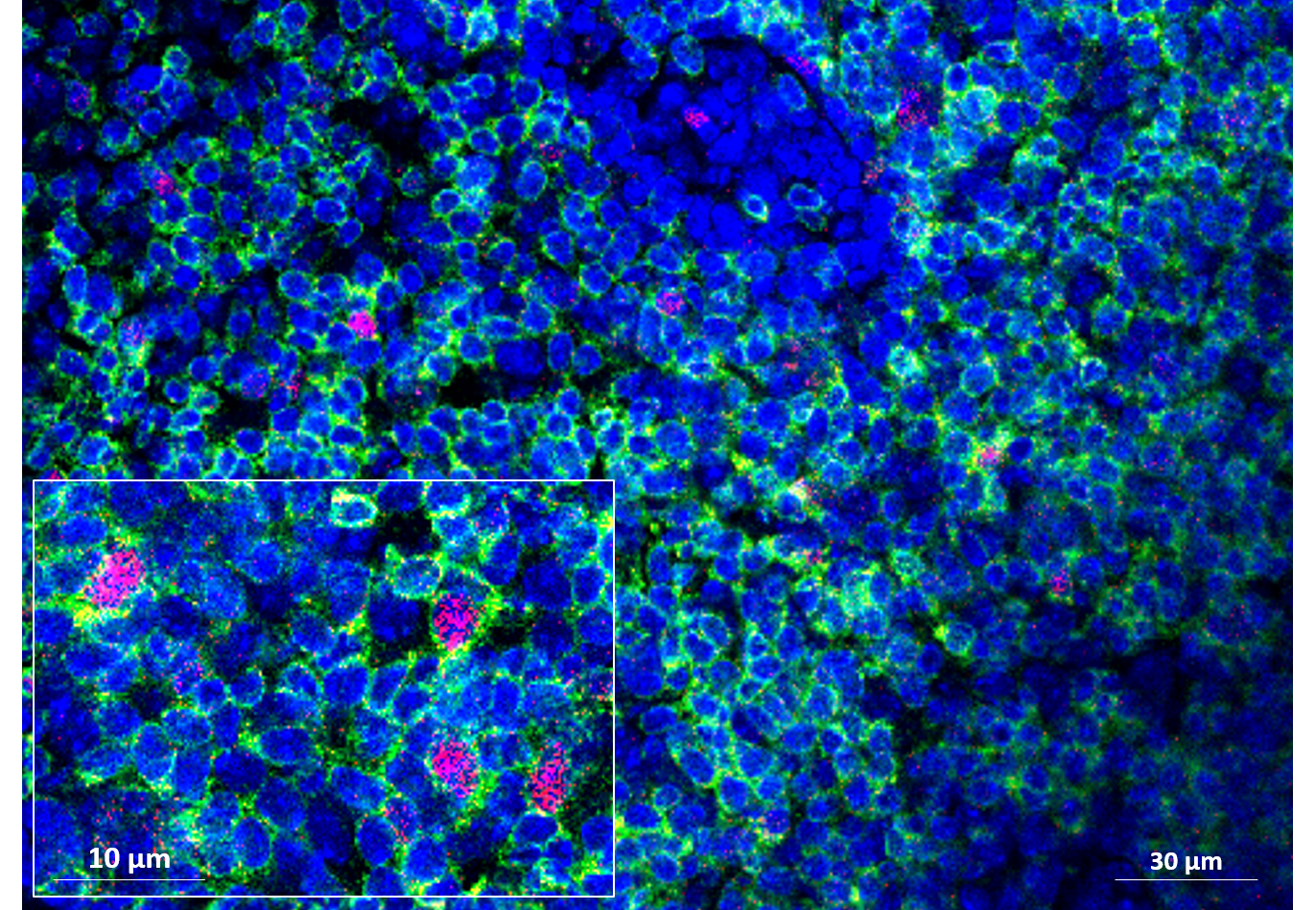

The rest of her career so far has been punctuated by major advances in the understanding of the microbiota and intestinal immunity. For example, with her team, the researcher demonstrated the key role of the segmented filamentous bacterium, a true ‘star of intestinal immunity’. The team is currently continuing to study this bacterium in order to identify its mechanisms of action and how the host controls its expansion in the gut.

In 2014, the integration of the team at the Imagine Institute was a major opportunity to develop new themes in the field of genetic intestinal diseases. In particular, Cerf-Bensussan and her colleagues have created a cohort of patients suspected of having monogenic intestinal disease. Thanks to their efforts, a genetic diagnosis was made for around 30% of those patients and a high-throughput sequencing-based diagnostic tool was developed. The team is also trying to establish a catalogue of genes essential to the balance of the intestinal barrier and to define their precise roles, where needed.

‘I’m delighted about this Grand Prize, which I see as the recognition of the importance of this interface that is constantly exposed – not just to a considerable mass of microbes but also to the multiple components of our diet and environment. It’s as if we had awarded the prize to the gut!’ concludes Cerf-Bensussan.

Thomas Baumert, Research Prize

© François Guénet/Inserm

© François Guénet/Inserm

As both a physician and a researcher, Thomas Baumert has furthered knowledge on fibrosis and liver cancer in order to develop innovative treatments to improve patient care. These efforts have earned him the Research Prize.

This passionate scientist is currently Director of the Institute for Viral and Hepatic Disease Research in Strasbourg. His team – which has around fifty people at present – is responsible for major advances in the field.

Their work on immune response and the entry of the hepatitis C virus into cells contributed to the treatments subsequently developed by private pharmaceutical companies. This is a significant step forward considering that hepatitis C was responsible for the deaths of many people from liver cancer twenty years ago, and that it can now be cured.

Other research published by his team, in collaboration with several international laboratories, testifies to Baumert’s dynamism and spirit of innovation – always at the service of patients.

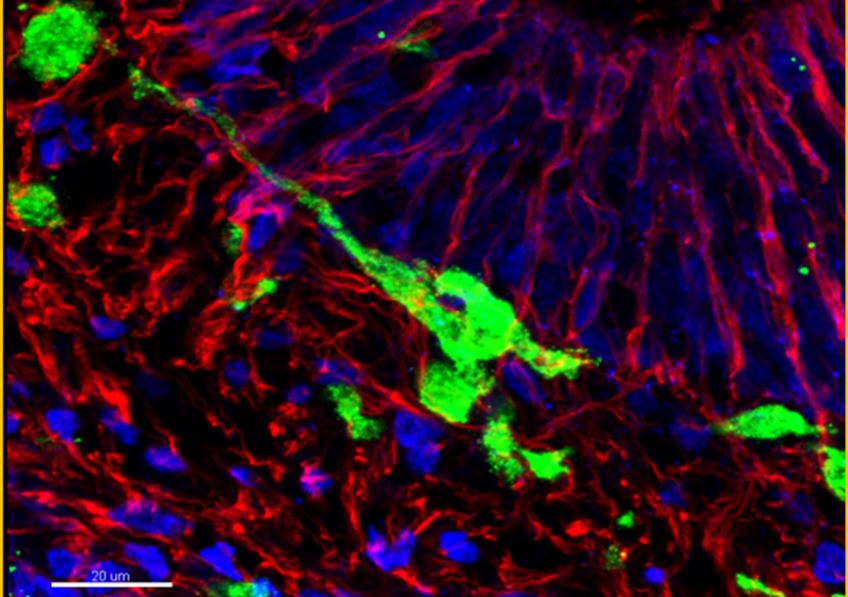

The scientists have: discovered a new therapeutic target for fibrosis and liver cancer – a protein overexpressed on the surface of diseased tissue cells called ‘claudin 1’; drawn up an ‘atlas’ of all human liver cells and their mechanisms of action; and developed a kind of ‘mini liver’ that mimics the prognostic signature of fibrosis and cancer.

Alexandre Loupy, Innovation Prize

© François Guénet/Inserm

© François Guénet/Inserm

Winner of the Innovation Prize, Director of the Paris Transplant Institute and the Paris Transplant Group, Alexandre Loupy is a nephrologist, biologist and biostatistician. Multifaceted expertise that enables him and his team to develop innovative tools to improve kidney transplantation.

One of the many advances in which he has participated is the 2013 discovery of antibodies that strongly increase transplant rejection.

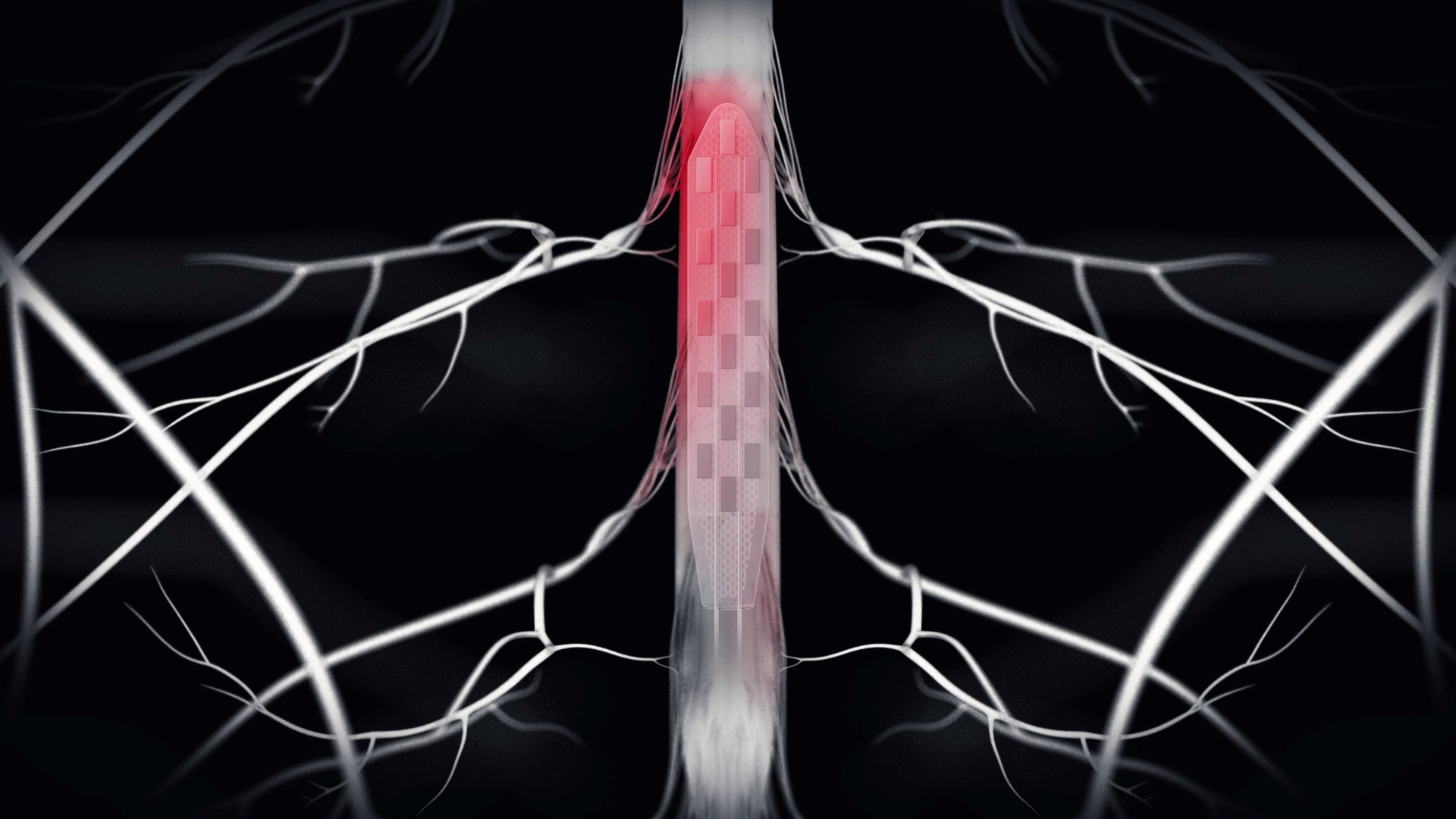

Then, more recently, his team developed an algorithm called iBox that uses biological, immunological and genetic parameters to predict graft rejection risk, graft survival and transplant patient mortality. A valuable tool to help doctors adjust monitoring and treatment.

The development of this algorithm was entrusted to Predict4Health, an Inserm, AP-HP and Paris Cité University start-up that Loupy founded in 2019. The algorithm underwent a clinical trial in Europe and has completed the regulatory process enabling its reimbursement to French social security beneficiaries. iBox is now used to monitor 10,000 patients in France and is currently under development to monitor chronic kidney diseases and heart, lung, and liver transplants.

Despite sharing his time between France and the US – where he teaches, Loupy has no intentions of abandoning the French research world and is immensely proud of this prize that rewards the work of his whole team.

Marina Kvaskoff, Opecst-Science and Society Prize

© François Guénet/Inserm

© François Guénet/Inserm

Marina Kvaskoff is an epidemiologist at the Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health Research (CESP) in Villejuif and devotes her time and energy to research into endometriosis – a long-overlooked gynaecological disease.

Her efforts to better understand and raise awareness of it have earned her the Opecst-Science and Society Prize.

Following her PhD, the researcher – who joined Inserm as staff scientist in 2016 – headed to the US to train at Harvard University with Stacey Missmer, a pioneer in endometriosis epidemiology and now Chair of the World Endometriosis Society.

Eager to better understand this disease that affects many women but about which little is known, she embarked on research in which she saw that certain exposures in childhood (passive smoking, dietary deprivation, intense physical activity, etc.) increase the risk of developing it. She also shows that endometriosis is linked to the risk of different cancers.

Important research, which has remained niche for too long, despite the support of Inserm. However, since 2018, the strong mobilisation of patient associations and celebrity advocacy have brought endometriosis out of the shadows. The disease is becoming a subject that is taken seriously by health authorities. In 2022, the French government announced its desire to set up the ambitious Epi-Endo programme on the epidemiology of endometriosis, led by Kvaskoff as part of the Women’s Health, Couples’ Health priority research programmes and equipment (PEPR).

Ghislaine Filliatreau, Research Support Prize

© François Guénet/Inserm

© François Guénet/Inserm

For thirty years, Ghislaine Filliatreau, Inserm’s Scientific Integrity Officer, has channelled all her energy and detailed knowledge of the research ecosystem into serving research. An approach that has earned her the Research Support Prize.

After joining Inserm in 1983 as a researcher in cellular neurobiology, she joined the French Ministry of Higher Education and Research twelve years later to work on the development of open archives – what is now known as ‘open science’.

She has also headed up the Science and Technology Observatory, which is tasked with devising indicators to support the definition and evaluation of research policies.

Experience that is as rich as it is varied, enabling her to fully understand the challenges of research and the reality of laboratories.

In 2016, she returned to Inserm as Scientific Integrity Officer, whose mission is not only to manage breaches of integrity, but also to prevent them by providing expertise and advice for the promotion of reliable and robust research.

A task that is close to her heart and which she fulfils with great energy and success. She also co-directs the LORIER programme (The organisation for ethical and responsible research at Inserm) and participated this year in the development of Inserm’s public speaking charter.

The Inserm Prizes

The Grand Prize pays tribute to a French scientific research player whose work has led to remarkable progress in our knowledge of human physiology, treatment and health research more generally.

The Research Prize honours a researcher whose work has particularly marked the fields of basic research, clinical and therapeutic research, and public health research.

The Innovation Prize is awarded to a researcher whose work has been the subject of entrepreneurial value creation.

The Opecst-Science and Society Prize honours a researcher, engineer, technician or administrative worker who stands out in the field of research promotion and through their ability to be in dialogue with society and attentive to the health questions of its citizens.

Finally, the Research Support Prize is awarded to an engineer, technician or administrative worker for significant achievements in the support of research.

Eating meals early could reduce cardiovascular risk © Freepik

Eating meals early could reduce cardiovascular risk © Freepik

© François Guénet/Inserm

© François Guénet/Inserm © François Guénet/Inserm

© François Guénet/Inserm © François Guénet/Inserm

© François Guénet/Inserm © François Guénet/Inserm

© François Guénet/Inserm © François Guénet/Inserm

© François Guénet/Inserm