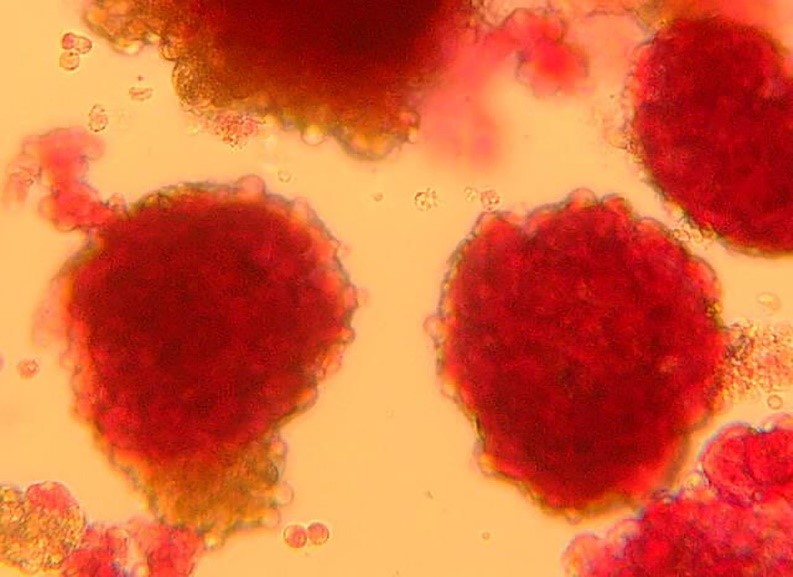

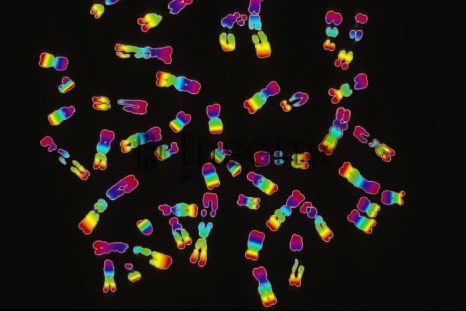

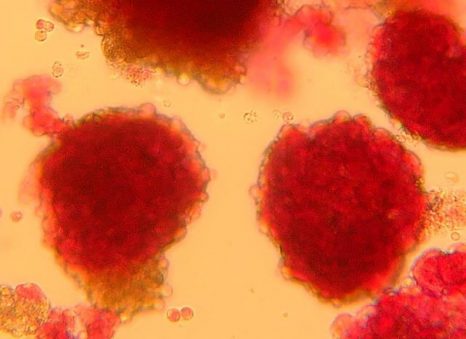

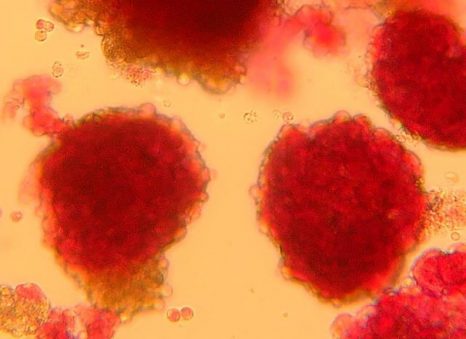

Pancreatic islets seen under the microscope ©François Pattou/Université de Lille

From the discovery of insulin in 1921 to the first ever pancreas transplants in the late 1960s, the recent history of type 1 diabetes research has brought scientific and medical advances which have transformed patient prognosis and quality of life.

In France and worldwide, researchers continue to strive to improve the management of patients. Here at Inserm, eleven teams distributed among nine units contribute their own endeavors. Their work primarily involves the characterization of pancreatic cells and improving knowledge of the disease (risk factors, genetic susceptibility, pathophysiological mechanisms) and its complications.

One of these teams, based in Lille, is exploring islet transplantation, a promising technique discussed in a new publication in Diabetes Care[1] and in an update in The Lancet[2]. Other very interesting avenues currently being explored include immunotherapy and the development of artificial pancreases.

I. Type 1 diabetes research at Inserm

The teams at Inserm are involved in various collaborative projects to bring about advances in the treatment of type 1 diabetes. The findings of some already look promising.

- EXALT (2014-2019)[3], with the participation of Christian Boitard’s Inserm team at Institut Cochin, was a project that aimed to evaluate the effects of an innovative immunotherapy on type 1 diabetic patients. Based on the administration of a peptide, the objective of this immunotherapy was to modify the autoimmune reaction directed specifically against the pancreatic beta cells. The first part of the project used experimental models to demonstrate that there is indeed an effect on the autoimmune reaction of diabetes. The results of the phase 1b clinical trial are currently being analyzed.

- Hypo-RESOLVE (2018-2022)[4], a European project currently being conducted by Éric Renard in Montpellier (Inserm 1191/JRU 5203), aims to consolidate scientific knowledge on hypoglycemia. The idea is to create a permanent clinical database, conduct studies to further elucidate the underlying mechanisms of hypoglycemia and perform a series of statistical analyses to define its prediction factors and consequences. In addition, the researchers also wish to calculate the financial cost of hypoglycemia in the countries of Europe.

- Artificial pancreas: Éric Renard and his colleagues have conducted research in collaboration with the University Of Virginia (Charlottesville, VA, USA) to create an artificial pancreas. The algorithmic system developed has been incorporated in the Tandem Control-IQ device, with a view to its commercialization (see photo below). Currently being trialed in 120 type 1 diabetic children in France as part of a national hospital-based clinical research program, interim-analysis data indicate that normal blood glucose levels are maintained for 71% of the 24-hour period, with a significant reduction of the time spent with abnormally high or low blood glucose levels. While its name might be confusing, the artificial pancreas is not actually a fake organ that will be transplanted into the patient but rather a technological device made up of three key elements: a sensor, a pump and an algorithm. The subcutaneous sensor continuously measures the patient’s blood glucose. The pump administers insulin through a fine cannula placed under the skin. The challenge of the artificial pancreas currently lies in the third part of the system: the algorithm capable of automatically making the link between the sensor and the pump.

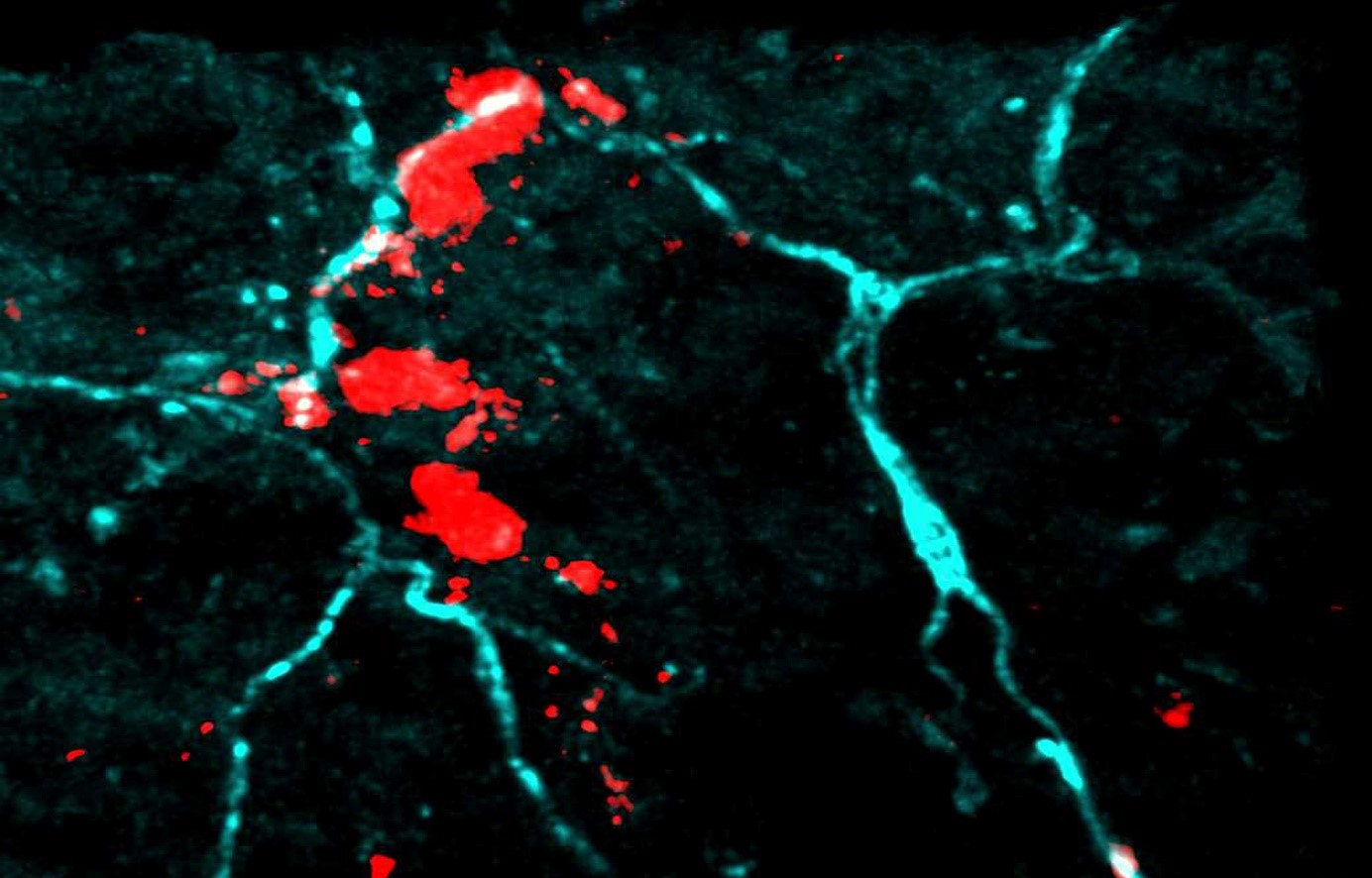

- Raphaël Scharfmann’s Inserm team at Institut Cochin has over the previous decade produced new cell models of type 1 diabetes, in the form of human beta-cell lines. His team is now seeking to develop innovative therapies based on the use of stem cells.

II. An alternative to insulin

a) Insulin-producing islets

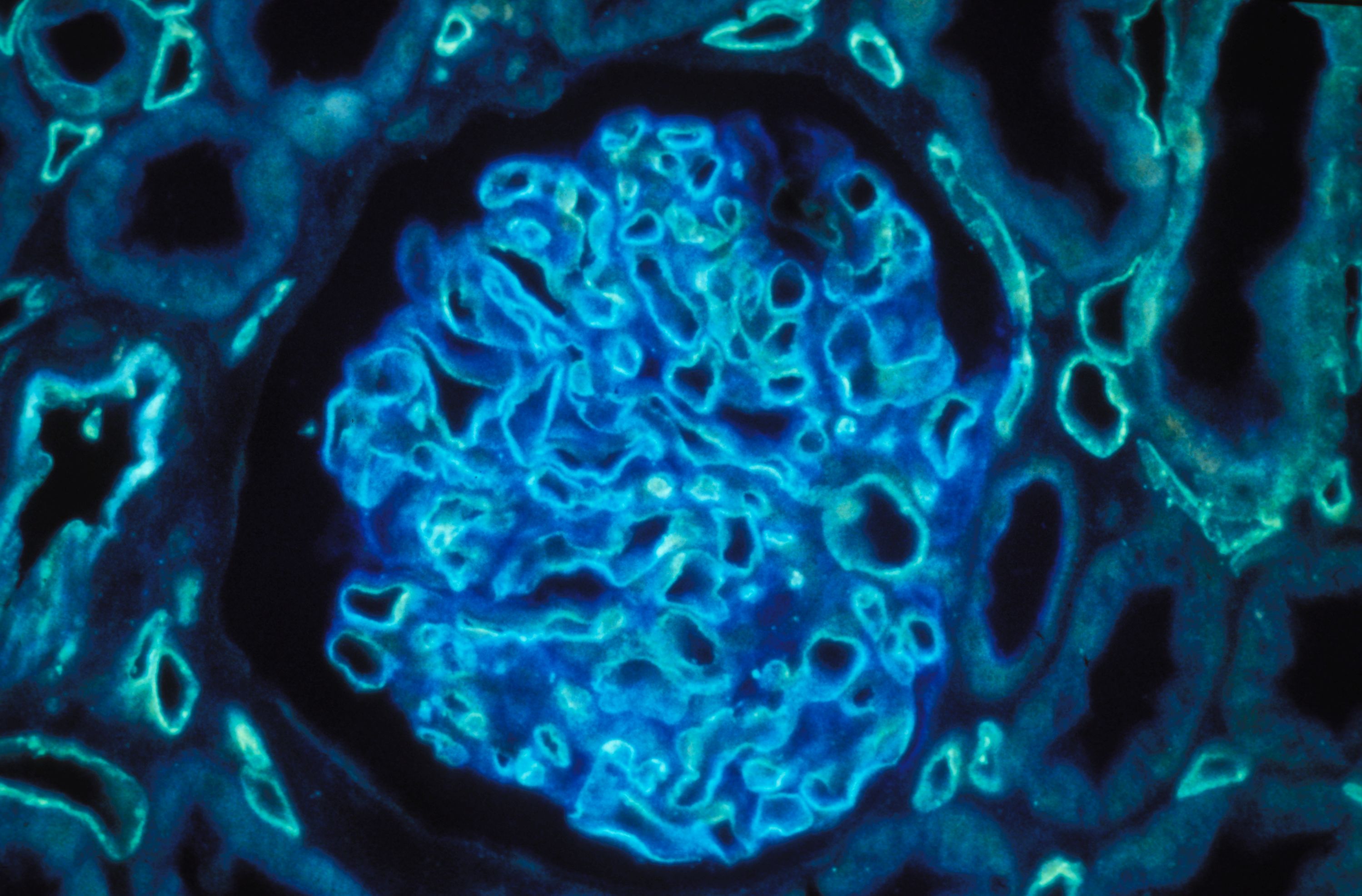

In this context of ongoing innovation, the allotransplantation of islets of Langerhans, these specialized cells in the pancreas that produce insulin, has also emerged as a particularly interesting therapeutic avenue. Over the previous two decades, François Pattou, Marie-Christine Vantyghem and Julie Kerr-Conte in Inserm unit 1190 Translational Research in Diabetes, and their colleagues in the surgical and endocrinology/diabetes departments of Lille University Hospital have been developing this approach, in which over 50 people have received transplants.

Beyond the indisputable benefit for patients, their research is a perfect illustration of the contribution of translational research and of how laboratories and hospitals can join forces to improve knowledge and treatment of the disease.

In France, 3.9 million people have diabetes, around 5% of whom have type 1. This form of the disease is caused by a deficiency of the hormone insulin, which leads to prolonged high blood glucose levels (hyperglycemia).[5] Type 1 diabetes is considered to be an autoimmune disease because it is caused by a dysfunction of the immune cells that identify the pancreatic islets of Langerhans as cells foreign to the body, and destroy them. These islets are therefore no longer able to fulfill their usual role of insulin production.

b) Principle of the transplant

At present, the reference treatment for type 1 diabetes is based on the administration of insulin, either by multiple daily subcutaneous injections or by pump. Patients have the use of human insulin analogs that make it possible to restore and maintain normal blood glucose levels.

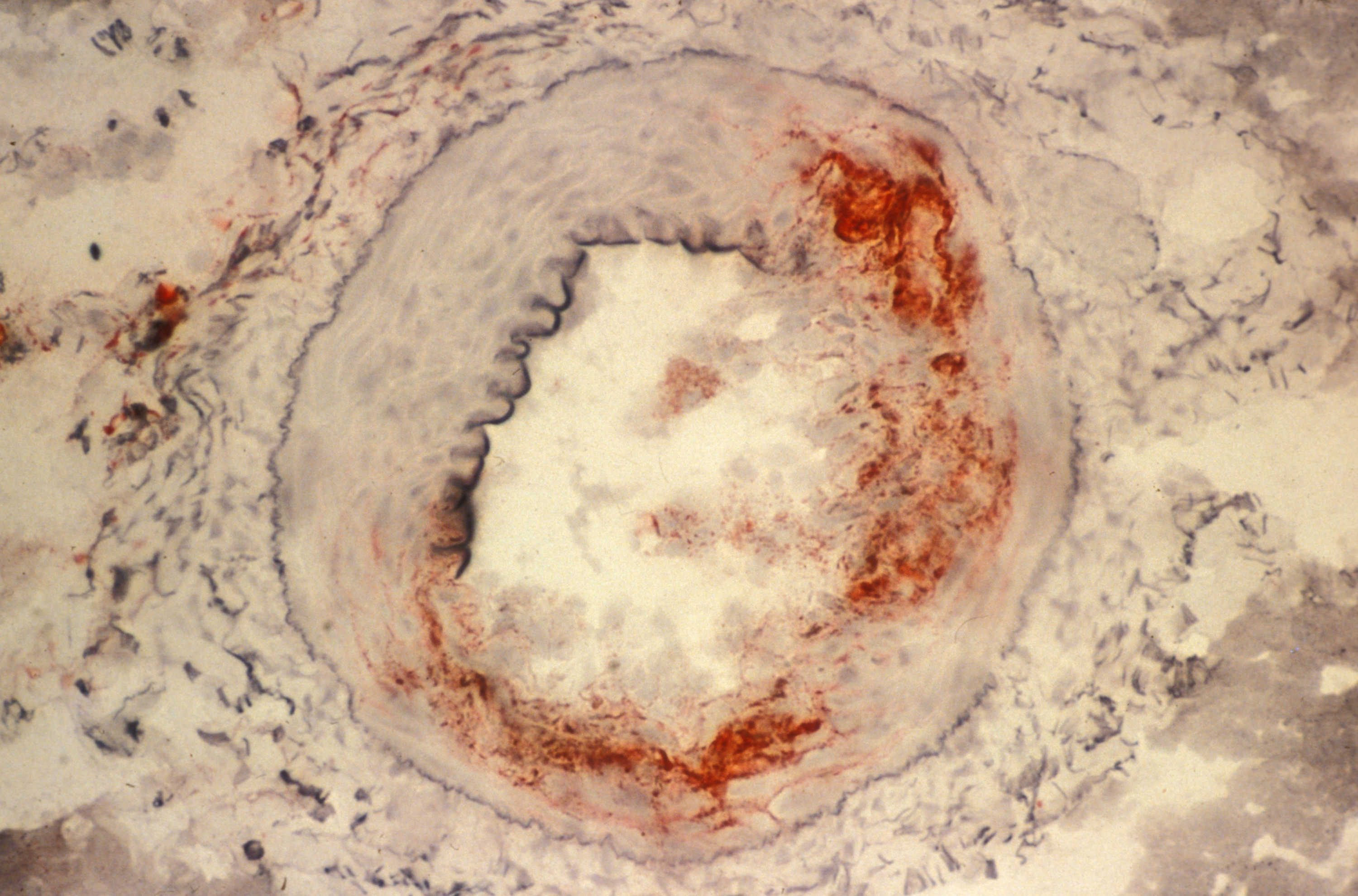

Nevertheless, some patients find that their blood glucose levels are not properly controlled with this treatment, despite strict observance of dietary and therapeutic advice. Severe complications can then develop. Poorly-controlled blood glucose can be harmful to the organs, affecting the heart and vessels to begin with, but also the small arteries that supply the kidneys, the nerves of the lower limbs, and the retina.

Alongside the technological approaches (insulin pump, glucose sensors and – soon – the closed-loop pump), the biological approach involving the transplantation of islets represents an essential step for diabetes research. By making it possible to restore almost physiological insulin secretion, the transplantation of insulin-secreting cells transforms the lives of patients, who until now had run out of all therapeutic options.

The principle of islet transplantation or diabetes cell therapy is to replace the destroyed pancreatic cells in order to restore regulated insulin production. This makes it possible to normalize patient blood glucose control and even discontinue the use of insulin. “Islet transplantation is offered to two types of patient: those who have very unstable, often longstanding, type 1 diabetes, particularly with severe hypos and/or hypo unawareness, and kidney transplant patients who are already taking immunosuppressants which then just need to be adjusted”, points out Vantyghem.

II. Two decades of transplants

a) The early days of islet transplantation

In type 1 diabetic patients whose renal complications justify kidney transplantation, the simultaneous transplantation of a whole pancreas has for a long time represented the most effective therapeutic alternative to insulin. A trend which could nevertheless reverse in coming years, given the non-negligible risks associated with the procedure. The pancreas is a fragile organ, difficult to remove from donors.

The injection of islets – i.e. only the useful, insulin-secreting, cells – is a procedure that is less complicated but equally as effective. “Pancreas transplantation is an effective procedure but carries a high risk of sometimes severe complications. In the beginning, pancreas transplantation did give better results in terms of blood glucose control. But great progress has been made in islet transplantation, which is also less risky, and can now be offered to patients who would not tolerate a pancreas transplant”, specifies Pattou.

The first tests and clinical trials of this technique date back to the late 1960s. However, the major turning point in the history of islet allotransplantation is considered to be the year 2000. This was the year in which Canadian researchers published the results of a clinical trial in the New England Journal of Medicine[6]. Thanks to pancreatic islet transplantation, seven type 1 diabetic patients became fully insulin-independent one year later, no longer requiring their insulin injections.

“After the year 2000, research into this procedure took off, with other successes reported worldwide – particularly by our group. The problem is that very few studies went on to focus on patients over the long-term – and we are the first to present the results of a 10-year study”, highlight Pattou and Vantyghem.

b) 10 years of follow-up

The new study, published in Diabetes Care by Pattou, Vantyghem and their teams, retraces the paths of 28 patients who had received an islet transplant between 2003 and 2012, half of whom had already received a kidney transplant for renal failure.

Prior to this research, various groups had already published results on the outcomes of islet transplant patients, but none had gone beyond a follow-up period of five years. All highlighted the clinical benefits for the patients and their improved quality of life. However, in the absence of rigorous longer-term follow-up, questions remain unanswered. Are the benefits of islet transplantation maintained beyond five years? What about the complications associated with taking immunosuppressants?

The protocol for performing islet transplant surgery has been established over the previous two decades by the team in Lille, drawing attention not just to the quality but also to the quantity of the islets used. “We chose to start by transplanting a large number of islets. If they come from a particularly robust pancreas containing many islets, one transplant can be enough. However, this situation is exceptional and one or two additional transplants are generally needed. The particularity of our program is to rapidly schedule new transplants, independently of the results of the first, to give patients every chance of achieving normal insulin production”, explains Pattou.

Islet transplant: a few words about the procedure

The isolation of islets now takes place in a number of specialist laboratories, in Lille by Kerr-Conte’s team and also in Geneva, Paris, Montpellier and Strasbourg, from pancreases taken from donors with brain death.

The preparation is then injected into the liver through a small abdominal incision or percutaneously in order to infuse the islets in the portal vein of the liver. The main risk of this procedure is thrombosis, meaning that patients must be given anticoagulants.

Pancreatic islets seen under the microscope – François Pattou/Université de Lille

c) Promising results

As part of their study, the patients were seen at the hospital at least once a year for ten years to check the condition of the transplant. The majority of the patients were seen quarterly. At each visit, the patient’s clinical situation, blood glucose control, exogenous (originating from outside the body) insulin requirements and the diabetic and treatment-related complications were evaluated.

The research team had chosen to study, as primary endpoint, insulin independence with normal blood glucose levels. The doctors wanted to determine the proportion of their patients able to maintain good blood glucose control, without the exogenous provision of insulin. The study highlights that this is the case after five years for half of the 28 patients, and after ten years for almost one third (28%). These findings are similar to those obtained with whole-pancreas transplantation.

The researchers have also shown that 80% of the patients had a transplant that was still functional after five years, with no major hypoglycemic events. After ten years, this remained the case for two-thirds of them. Finally, there was no significant deterioration in kidney function, despite the possible renal toxicity of the immunosuppressants, which was probably compensated for by precision dose adjustment and the excellent blood glucose control obtained in the majority of the patients.

These results show that such a procedure can considerably improve the blood glucose levels of uncontrolled type 1 diabetic patients, protect them from the potentially fatal risk of severe hypos or hypo unawareness, avoid the serious complications associated with the disease and significantly improve their quality of life.

In order to understand why the procedure has greater long-term efficacy in some patients rather than others, several avenues are emerging. “It would appear that there is a signal in favor of women, with some experimental elements showing that the presence of estrogens is favorable to the islets’ survival. The patients with the best long-term results are particularly those who had regained good blood glucose control just after the transplant. To optimize this, attention needs to be paid to the quality and quantity of the islets initially transplanted”, state Pattou and Vantyghem.

An application to obtain reimbursement status for islet transplantation from France’s National Authority for Health is in progress. The response is expected for 2020.

III. What does the future hold?

Various difficulties remain, notably the potential immunological rejection of the transplanted cells, and the limited number of human insulin-secreting cells available for transplant given the current shortage of donors.

Indeed, to avoid rejection of their transplant, patients are required to take immunosuppressant treatment which has a certain number of side effects. Several teams are currently working on finding new solutions to avoid this phenomenon. In addition, in order to develop alternatives to human donors, a number of teams worldwide are currently conducting studies that aim to produce islets from pluripotent stem cells, and successfully transplant them[7].

These two issues could be resolved through a joint approach in order to disseminate diabetes cell therapy more widely: “The Holy Grail would be to produce islets from stem cells in the laboratory and then transplant them inside capsules of biomaterials that shield them from the immune system”, highlights Pattou.

In addition, various research is ongoing to develop fully autonomous artificial pancreases. At present, the blood glucose control obtained with these external devices remains inferior to that obtained with the transplant and the “biological” restoration of insulin secretion. “These approaches nevertheless prove complementary and are offered in accordance with the profile of each patient”, specifies Vantyghem

The publication of the islet transplantation results after 10 years is a significant new step in the treatment of type 1 diabetes. These findings show that the cell therapy can work over the long term if sufficient islet mass is transplanted. This research opens up very interesting avenues for the various teams working on new sources of insulin-secreting cells, especially those produced from stem cells and which will make it possible to compensate for the shortage of donors.

IV. What the patients say

Michèle, age 61, transplanted 14 years ago

©Alain Vanderhaegen – Communication Division of Lille University Hospital

“Your daughter won’t survive beyond the year 2000. She will never marry or have children”. That was how an unsympathetic doctor informed Michèle’s mother that her child had type 1 diabetes. At the time, Michèle did not really understand what was happening. This was in the 1970s and for her the year 2000 was very far off. She did not feel ill. Yes, she had lost a lot of weight recently but she did not feel unwell.

Then, all of a sudden, everything changed. Her resulting stay in hospital, being the only child in a ward of elderly people suffering from major diabetes complications, including amputations, was genuinely traumatic. “Psychologically, it was very tough. I lived a life of untruths, to avoid other people’s questions”, she explains.

Administering the treatments was difficult. The needles had to be sharpened, the syringes boiled and the insulin injected with a constant feeling of shame, a desire to hide. Life went on for Michèle, she held on. She met her husband Jacques, had a son, both of whom support her. From a young age, her son knew what to do when his mom had a hypo, he knew to get sugar from the cupboard when it was needed.

But her severe hypos became increasingly frequent. Some days, up to five or six in succession, leaving Michèle and her loved ones exhausted. Her diabetes specialist, having met the Lille teams at a conference, decided to refer her for islet transplantation. It took her one year to decide to take the plunge, which she did in 2006. She then had three grafts in quick succession. Immediately after the third, Michèle was able to discontinue her insulin injections. “The fact that the cells come from deceased donors bothered me. I was also afraid that the transplant would change me. In fact, it has changed my life but I’ve stayed the same, except that these three people are always with me. That shadow will never go away. Progress in transplants using stem cells would be a major step forward”, she emphasizes.

It has been 14 years now since Michèle stopped using insulin, since she has been taking immunosuppressants every day, with no major side effects. For both her and her loved ones, it is a liberation. “I’m a free woman once more – my husband and I can do things independently again. Sometimes I worry about the aging of the transplant, as going back would be unthinkable”, she says.

Carole, age 60, transplanted 4 years ago

©Alain Vanderhaegen

At 14 years of age, Carole was a freshman at boarding school. An experience that she did not enjoy, especially since she could not stop fainting. However, when she changed schools, things seemed to improve. She felt good, and no longer gave her fainting a second thought. Until a medical visit that revealed sugar in her urine, followed by a blood test confirming the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes.

Back at school, after a month in hospital, she was the subject of a lot of attention. “I could say anything I wanted in class, because people would say: “it’s not her fault, poor thing, she’s diabetic“. So I made the most of it, I had fun”, she explains.

She tolerated her treatment well, ate more or less normally, got her high school diploma and became an elementary school teacher. At work, she always had bottles of orange juice with her in case of hypos.

But those hypos became increasingly severe, encroaching on her daily activities and deteriorating her quality of life. “When giving birth to my daughter, the doctors did not take my diabetes into account. I had a pulmonary edema and was hospitalized elsewhere. I didn’t see my baby for two weeks, so I went on hunger strike so that they would let me see her. When I left the hospital, I had a hypo one morning. All of a sudden, I couldn’t remember that I had a daughter – I’d forgotten her. Had I been alone, I would have been capable of going out and leaving her behind”, she says.

One day, a friend told her about the islet transplants in Lille which he had heard about on the radio. Carole discussed it with her diabetes specialist who promised to look into it. In the end, it was Carole who found the contact details of the team herself.

Transplanted in 2015 and 2016 on three occasions, Carole is keen to make the most of her life. She has been insulin-independent since the second transplant. Five years later, she continues to tolerate the immunosuppressants well, which she never forgets to take. Her hypos have stopped. She can now drive, do sport, go for walks by herself without having to keep her husband informed. “I can even eat biscuits when my family makes them. But I’m so used to not eating sugar that I actually don’t like it. The transplant changed my life at a time when I was no longer doing anything by myself. These islets are my friends, I’ve given them their own name and I celebrate their anniversary”, she smiles.

Béatrice, age 54, transplanted 1 year ago

©Alain Vanderhaegen

The adolescence of Béatrice was disrupted by the discovery of her diabetes. Originally from the countryside near Rennes, no-one she knew had heard of the disease until her diagnosis at the age of 11. It was difficult to begin with: at school, no-one made the effort to understand her situation. She was obliged to eat in the canteen kitchen and often found herself alone in the school yard. Her insulin injections improved things a little, although there were side effects, particularly weight gain, with each dose increase. Béatrice also suffered from discrimination, which continued into her professional life.

Over the years, new technologies emerged to help patients like Béatrice control their blood glucose better, such as insulin pumps with automatic shut-off and sensors that continuously monitor blood glucose. Nevertheless, there were also disadvantages: her hypos would trigger an alarm at any time of the day or night. “It was very difficult to live with. When I had the transplant my husband said that “we could finally get some sleep“. Our quality of life improved markedly”, she emphasizes.

It was when reading an article in the journal of the French Association of Diabetics (AFD) that Béatrice discovered islet transplantation. She was tired, she had just lost her job. “I had the impression that I’d reached the end of the road, I needed a new solution in order to survive. Quite simply, to continue to live. As I was reading the article, I had the immediate feeling that the procedure was for me“, she explains.

It took two years before she was able to convince her diabetes specialist to refer her on, and that she was finally able to meet the Inserm-Lille University Hospital team. At the end of 2018, Béatrice received three transplants and became insulin-independent very soon afterwards. “For me the transplant was a huge gift. Out of respect for the donors, I need to keep fighting. I want to keep them alive, I call them my little angels”, she explains.

Although the immunosuppressants are not without their side effects, notably pins and needles in the legs, Béatrice acknowledges that they are in no way near as bad as the complications related to her type 1 diabetes. “My diabetes was always on my mind, I had the impression that my life revolved around it. We’ll see how I get on, and how the transplant holds up over the next few years, but right now I’m optimistic. For the first time in a long time, I have hope”, she says.

Glossary

Islets of Langerhans: the cells of the islets of Langerhans (or pancreatic islets) are endocrine cells of the pancreas whose primary function is to produce insulin. The islets of Langerhans are complex micro-organs disseminated in the exocrine pancreas.

Allotransplantation: the most common form of transplantation, in which the donor and recipient are the same biological species but strangers to each other.

Xenotransplantation: transplantation in which the graft comes from a biologically different species – for example, pigs.

Pluripotent stem cells: cells able to multiply infinitely and differentiate into the various types of cells that make up an adult organism.

[1] https://care.diabetesjournals.org/sites/default/files/care_upcoming/DC190401_ADVANCEDCOPY_STAMPED.pdf

[2] “Advances in β-cell replacement therapy for the treatment of type 1 diabetes”.

Vantyghem MC, de Koning EJP, Pattou F, Rickels MR.

Lancet. 2019 Oct 5;394(10205):1274-1285.

[3] https://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/110445/reporting/en

[5] https://www.inserm.fr/information-en-sante/dossiers-information/diabete-type-1

[6] Islet Transplantation in Seven Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Using a Glucocorticoid-Free Immunosuppressive Regimen, New England Journal of Medicine, July 2000. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM200007273430401

[7] Https://www.ajd-diabete.fr/le-diabete/tout-savoir-sur-le-diabete/le-traitement/ (only available in French)