An international study, conducted by researchers from the Institute for Development Research (IRD), Inserm and Institut Pasteur and their Guinean partners (Donka University Hospital, Macenta Hospital, National Institute of Public Health, and University of Conakry, confirms that Ebola virus persists in the semen of survivors of the epidemic in Guinea, for up to 9 months after their recovery. These results, which recall the importance of monitoring survivors in order to prevent the risks of new epidemic outbreaks, are published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases on 3 May 2016.

(c) IRD/ Eric Delaporte

PostEboGui: multidisciplinary monitoring of a cohort of Ebola survivors

The objective of the PostEboGui1 programme, which has been conducted in Guinea since November 2014, is to monitor, for 2 years, a cohort of over 700 adults and children who survived2 the most serious Ebola epidemic in West Africa, in 2014. The researchers are developing a multidisciplinary approach (clinical, virological, immunological, social, and public health) in order to identify the clinical and social sequelae of the epidemic, as well as the potential risks of reactivating the virus, or transmitting it sexually

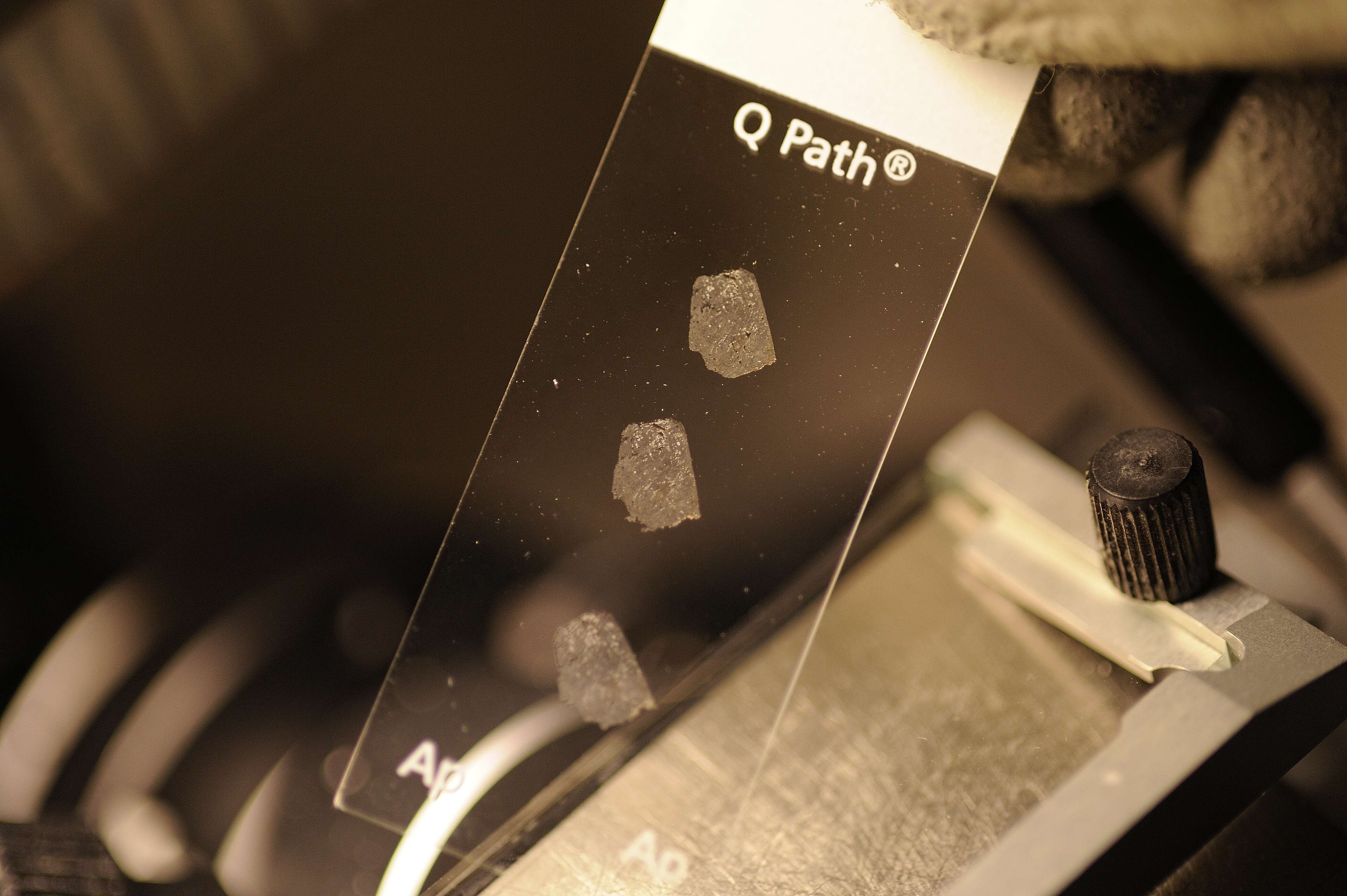

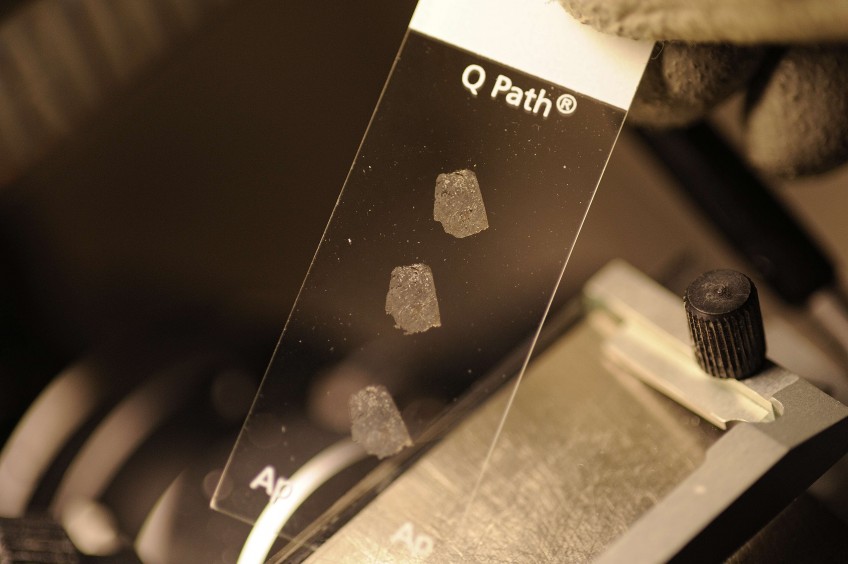

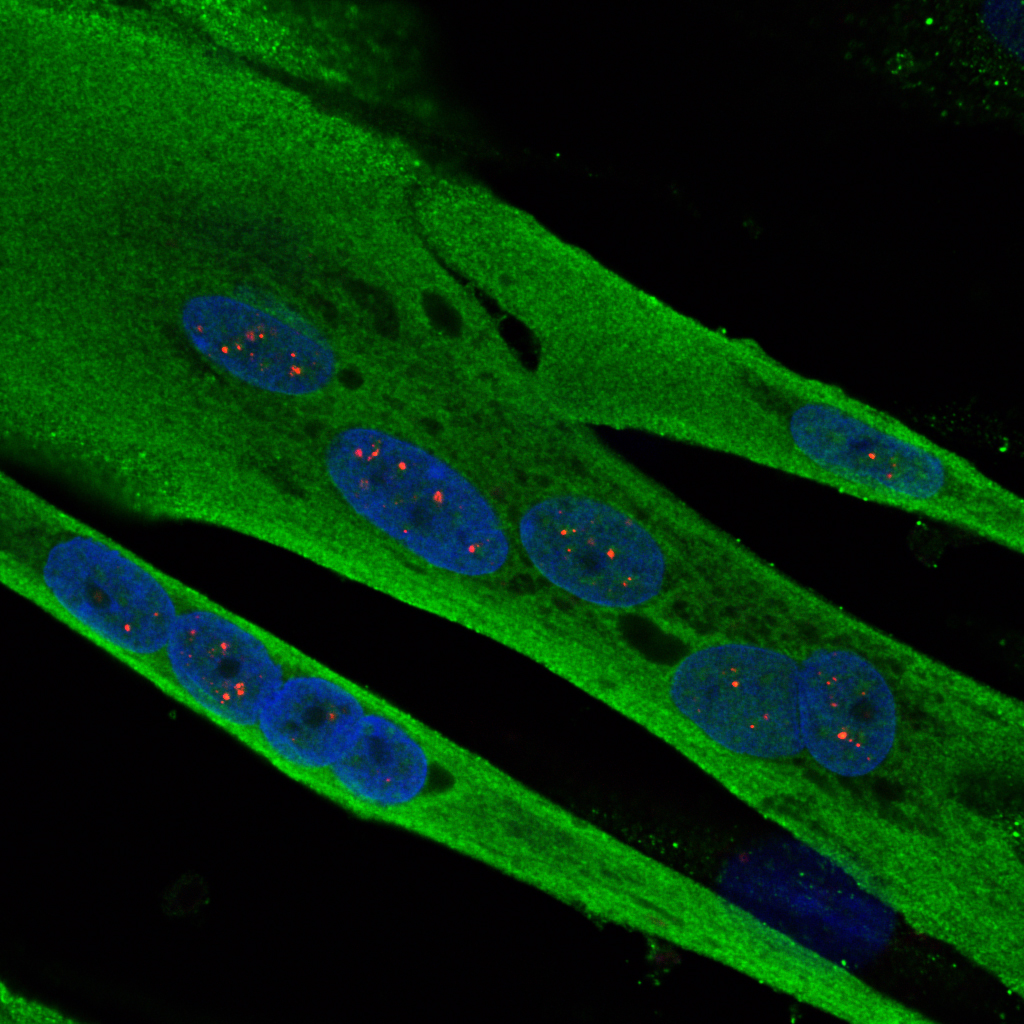

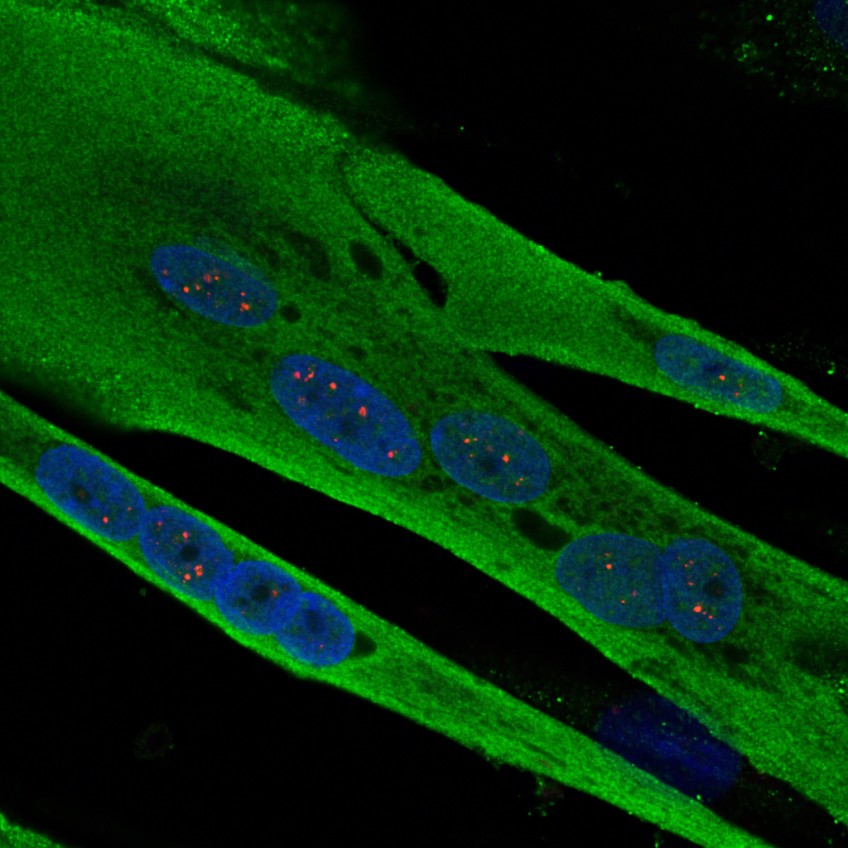

In this study, the researchers monitored the first 450 patients from the PostEboGui programme, both men and women, for 1 year. They took specimens of body fluids (tears, saliva, faeces, vaginal fluids and semen), on the first day of the study, and every 3 months thereafter. In order to detect the presence of the Ebola virus in these fluids, the researchers used molecular biology techniques employing the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and detection of ribonucleic acid (RNA), in hospitals in Guinea.

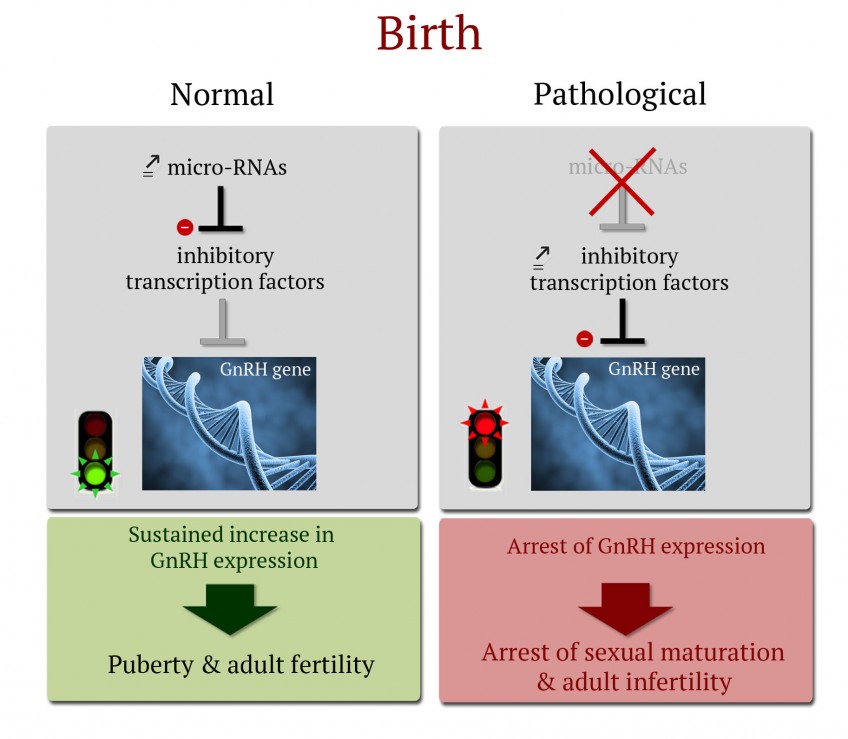

Presence of the virus in the semen for up to 9 months after recovery

The results relate to 98 specimens taken from 68 different people. Ebola virus was detected in 10 specimens taken from 8 men, for up to 9 months after recovery. In addition, the researchers showed that the persistence of the virus in semen decreases with time: the virus, present in 28.5% of samples taken between the 1st and 3rd months, was subsequently detected in only 16% between the 4th and 6th months, in 6.5% between the 7th and 9th months, 3.5% between the 10th and 12th months, and finally 0% after 12 months.

Improve survivor monitoring to limit resurgence of the epidemic

These results confirm those published in October 2015 in the New England Journal of Medicine on a cohort of survivors in Sierra Leone. They emphasise the need to recommend, at international level, the use of condoms by survivors in the months following their recovery.

Furthermore, the researchers insist on the importance of developing survivor monitoring, or even making it systematic, in order to limit the risks of a recrudescence of the epidemic.

Under the Ebola Task-Force, researchers are involved in monitoring survivors, especially in Guinea, from different aspects: surveillance of clinical and psychological sequelae, and risks of virus reactivation in patients who have recovered. They also focus on viral reservoirs in humans (the sites of “immune privilege” constituted by the eyes, brain and gonads).

In 2016, other research programmes will complete the scheme:

- FORCE: This is a therapeutic trial conducted by Inserm in men showing traces of virus in the semen (treatment based on the antiviral agent favipiravir).

- ContactEboGui: The objective of this project is to monitor people who have had contact with people who have been infected and declared cured (monitored under the PostEboGui programme), and who could have developed largely asymptomatic undiagnosed infections, in order to improve knowledge on the dynamic of the epidemic, and to identify the risks of secondary transmission and understand the routes of transmission.

- Réservoir: This project is focused on the source of the epidemic, particularly the animal reservoir for the virus, in Guinea, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Cameroon, Congo and Gabon, in order to prevent future epidemics.

Research programmes initiated at the start of the epidemic in 2014 under the aegis of the French National Alliance for Life Sciences and Health (Aviesan) are also being pursued, in the areas of disease diagnosis, clinical trials, and human and social sciences.

1 Funded by the Interministerial Ebola Task-Force, IRD and INSERM, PostEboGui is conducted by the TransVIHMI joint international unit for translational research on HIV and infectious diseases, in partnership with the University of Conakry, the infectious disease department at Donka University Hospital, Macenta Hospital, INSP, and the Socio-Anthropological Analysis Laboratory of Guinea (LASAG) at Sonfonia University.

2 I.e. over half of the patients declared cured in the country.