How will the traumatic events of the terrorist attacks of 13 November 2015 evolve in people’s memories, whether collective or individual? How does individual memory feed on collective memory and vice versa? Is it possible, by studying cerebral markers, to predict which victims will develop post-traumatic stress disorder and which will recover more quickly? These are a few of the questions addressed in the ambitious 13-Novembre program, coordinated by the CNRS, Inserm and héSam Université, with the collaboration of numerous partners. This transdisciplinary research program, codirected by the historian Denis Peschanski and neuropsychologist Francis Eustache, is based on the collection and analysis of the accounts of 1000 volunteers, interviewed four times over ten years. Involving several hundred people, this study is a worldwide first in terms of size, number of disciplines encompassed and protocol used. Results are expected to benefit the socio-historical and biomedical fields, but also have implications for public policy and public health.

Following the appeal launched last November[1] by Alain Fuchs, president of the CNRS, the research community is seeking to elucidate the issues facing society in the wake of the terrorist attacks that hit France in the course of last year. This call for projects gave rise to 13-Novembre, an interdisciplinary program that will run for 12 years. Coordinated by the CNRS and Inserm, in collaboration with héSam Université, it aims to study the construction and evolution of memory after the attacks of November 13th 2015, and also the relationship between individual and collective memory. “The 13-Novembre project illustrates the role of the CNRS, which is to support two scientists set to monitor studies involving 150 researchers from different disciplines in a long-term program of unparalleled scope,“ Alain Fuchs says. “From the very beginning, Inserm has been committed to the project, which combines human and social sciences and the latest advances in the neurosciences. This ambitious interdisciplinary program will answer the questions we are asking ourselves. I believe that this is part of the mission of two organizations like Inserm and the CNRS,” says Yves Lévy, CEO of Inserm.

1000 people monitored over 10 years

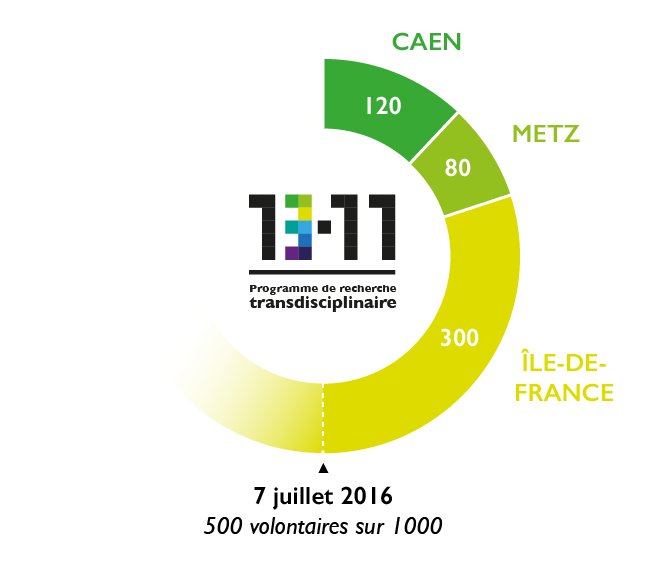

The testimonies of 1000 volunteers will be collected and analyzed. Some of these volunteers experienced the events at close hand: survivors, their family and friends, the police, the military, the fire brigade, the doctors and caregivers involved. Others were affected indirectly, i.e. the residents and users of the affected neighborhoods; Parisians from other areas; and finally, inhabitants of several French cities, including Caen and Metz.

The scale of this study makes it novel: the 1000 participants will be followed for 10 years over four campaigns of filmed interviews (in 2016, 2018, 2021 and 2026), with the contribution of the INA (which will conduct the Paris interviews) and ECPAD[2] (for the interviews outside of Paris). Its design is also unprecedented as the guidelines for the interviews were written jointly by historians, sociologists, psychologists, psychopathologists and neuroscientists, in such a way that the material collected is used by each discipline. This study is a world first.

Individual testimonies will be put in perspective with the collective memory as it is built over the years: television and radio news broadcasts, press articles, reactions on social networks, texts and images of commemorations, etc., are all examples of records held by the INA and analyzed by its research teams, in relation with other laboratories. Additionally, a partnership with the Crédoc[3] will make it possible to gauge public opinion at the dates of the interview campaigns. Eleven specific questions were thus integrated into the Crédoc’s traditional half-yearly questionnaire in June and July 2016.

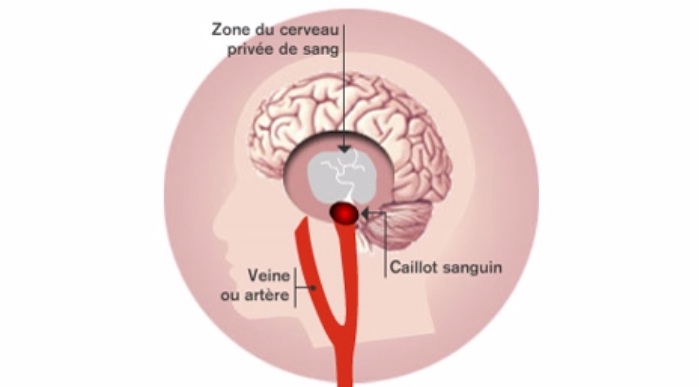

A biomedical study named “Remember” will be performed on 180 of the 1000 participants: 120 people directly affected by the attacks, some of whom are suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, and 60 who live in Caen. Interviews and brain MRI scans, conducted at the same frequency as the video interviews, will help to shed light on the impact of traumatic stress on memory (including intrusive thoughts and images, characteristic of post-traumatic stress disorder), and to identify markers associated with cerebral resilience to trauma. The participants, of course, will not need to be re-exposed to traumatic thoughts or images.

In parallel, the “ESPA” (post terrorist attack public health study) was initiated by Santé publique France[4] in collaboration with the 13-Novembre program in order to analyze—via an Internet questionnaire—the psychotraumatic impact of attacks on those directly exposed, but also the validity of healthcare channels.

Transdisciplinary study and civic commitment

The program is of crucial interest for all of the scientific disciplines represented. Historians and sociologists will try to understand how individual testimonies and collective memory are co-constructed. The linguist will measure the evolution of vocabulary and syntactic constructions. The neuropsychologist will focus on the consolidation and reconsolidation of memory and its functioning, which depends on whether one has experienced the event itself or is recalling the conditions in which they heard of it. As for the neuroscientists, they will work on the modifications to mental representations, post-traumatic stress disorder and the potential to eliminate painful memories. The psychopathologists will concentrate on the impact of the attacks on self-image, and will look into defense mechanisms or the relationship with destructiveness. In addition, the 13-Novembre program will be useful for criminal law, victim support policies, crisis management and commemorative practices. The filmed interviews will also have a heritage value: they will preserve and transmit the memory of the November 13th attacks. This is a civic commitment by the scientific community and the INA and ECPAD professionals who will be in charge of the recordings and documentary descriptions, as well as of making them available to researchers and archiving them permanently.

This program also takes some of the multidisciplinary concepts and methods developed by Denis Peschanski and Francis Eustache on the collective memory of World War II and September 11th and applies them to the Paris terrorist attacks within the framework of the “Matrice” Equipex (equipment of excellence) project, coordinated by héSam Université and in which the INA is already a partner. For the two researchers, it is impossible to understand collective memory without considering the cerebral dynamics of memory. Likewise, these dynamics cannot be fully grasped without considering the contribution of social determinants. The researchers were also inspired by the questionnaire in print elaborated by US psychologist William Hirst as part of a survey carried out, a week, a few months and a few years after the terrorist attacks of September 11th 2001. A comparative analysis of the two studies is also planned.

Multiple partners and supports

The 13-Novembre study started on May 13th in Caen (northwestern France) and June 2nd in Bry-sur-Marne (Paris region) for the filmed interviews. The biomedical study Remember started on June 7th at the biomedical imaging facility “Cyceron” in Caen in collaboration with Normandie Université. The call for volunteers is ongoing, notably via the French daily Le Parisien-Aujourd’hui en France (and its website). The first findings should be available in autumn 2017 and final results are expected in 2028, two years after the last interviews.

The CNRS and Inserm are in charge of coordinating the scientific aspects of the 13-Novembre program, while the administrative side has been entrusted to héSam Université. 13-Novembre is funded by the French Research Agency (ANR) as part of the French government’s Investments for the Future Program (PIA).

The program involves several research laboratories:

- Centre de recherche sur les liens sociaux, Cerlis (CNRS/Université Paris Descartes/Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3),

- Laboratoire Neuropsychologie et imagerie de la mémoire humaine (Inserm/EPHE/Université de Caen Normandie),

- Institut des systèmes complexes – Paris-Île-de-France (CNRS),

- Laboratoire Neuropsychiatrie: recherche épidémiologique et clinique (Inserm/Université de Montpellier),

- Centre de recherche sur les médiations (Université de Lorraine),

- Laboratoire Bases, corpus, langage (CNRS/Université Nice Sophia Antipolis).

It has a large number of associated partners:

- INA,

- Santé publique France,

- ECPAD,

- EPHE,

- Archives nationales,

- Archives de France,

- Université Paris 1 – Panthéon Sorbonne,

- Université de Caen Normandie,

- Cyceron biomedical imaging facility

- Caen University hospital,

- Le Parisien- Aujourd’hui en France national daily,

- Universcience,

- Crédoc.

It also benefits from the support of several ministries, local authorities and associations:

- Ministry of National Education, Higher Education and Research,

- Ministry of the Interior,

- Ministry of Culture and Communication,

- Secretary of State for Defense, chargé des Anciens combattants et de la Mémoire

- Paris authorities,

- 10th arrondissement [borough] local authorities in Paris,

- 11th arrondissement [borough] local authorities in Paris,

- The town of Saint-Denis,

- The urban community of Caen la mer,

- Normandy region,

- Normandie Université

- Institut national d’aide aux victimes et de médiation (Inavem),

- The association “Life for Paris : 13 novembre 2015”,

- The association “13 novembre : Fraternité et Vérité”,

- The association “Paris aide aux victims”,

- B2V joint social protection group

- Institut mémoires de l’édition contemporaine (IMEC).

[1] See: https://intranet.cnrs.fr/intranet/actus/160225-attentats-recherche.html (in French).

[2] Établissement de communication et de production audiovisuelle de la Défense.

[3] Centre de recherche pour l’étude et l’observation des conditions de vie.

[4] Santé publique France is the new public health agency formed from the amalgamation of the Institut national de prévention et d’éducation pour la santé (Inpes), Institut de veille sanitaire (InVS) and Etablissement de préparation et de réponse aux urgences sanitaires (Eprus), on May 1st 2016.